(Un) dependence Day: 1847

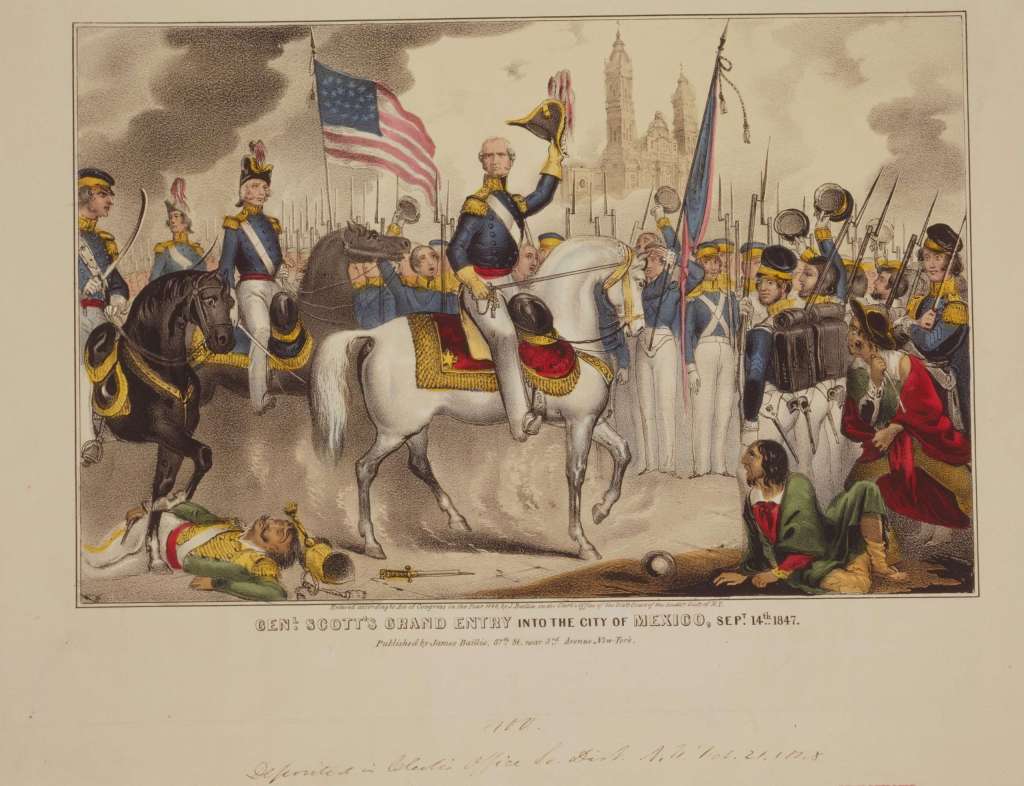

It may be Friday the 13th, 2024, but the unluckiest day in Mexico was a Monday: 13 September 1847. Around 8 AM that day, Santa Anna — despite promises to fight the invading US street by street — withdrew his forces from Mexico City. Scott would later claim (and US historians usually accept it as gospel) that other than some rioting by prisoners who escaped from the local jails, there wasn’t all that much resistance, but Manuel Payno (a lieutenant-coronal in the Army at the time). and Vicente Riva Palacio (then a cadet, and survivor of the Battle of Chaputepec), as well as other Mexican historians, like Guillermo Prieto, paint a very different story.

While true that Riva Palacio, as a “man of letters” sometimes “embellished” the story (notably in a memorial address on the anniversary of the Battle of Chaputepec, raising four that he mentioned by name, to mythic status as the “Niños Heroes”) the carefully documented “El libro roja”written in collaboration with Payno and others notes that Scott had recruited ann “advance force” in Puebla.. from their own prisons and jails. Before entering the city, he sent in his mounted and equipped team of “muderers, rapists, and… some just very bad people” to run amok and “soften up” civilian resisters.

The regular army, however, despite the odds, did face fierce resistance, although kitchen knives, rocks, old muskets, and even flowerpots were no match for artillery and trained sharp-shooters. Buildings from which attacks on US soldiers were attacked were leveled with cannons, and the inhabitants — male, female, and child — were massacred. Still, it took two days before the Stars and Stripes were finally raised over the Palacio Nacional, although the first attempt failed… some unknown patriot having shot the unluckey trooper assigned by Quitman to hoist the banner.

Even during the occupation, while the elites and the US “diplomats” worked out a deal to take the land the US craved, there was continued low-key resistance in the city. US soldiers would be mugged (or worse) if on their own, and allegedly, patriotic street walkers joined in, those with syphilis finding a way to give their all, and — in an era when there was no effective treatment — to at the very least die for their country.

History, it’s said, is written by the victors, and the hstiory and myyths of the losing side in a conflict are often left to find rationales for their defeat. But, in putting the focus on the villains and traitors (like Santa Anna) we miss that history comes from below… not the oligarchs and traitorous generals, who rolled over in the face of what U.S. Grant would later call “the worst injustice one nation has ever done to another”, but in those anomalous nobodies that stood up to that injustice, and should be the mythic heroes we manage to cull from the flames of war.

Sources:

Payno, et. a.. La libro roja (1905, A. Polo, Mexico).

Jay, William. The Causes and Consequences of the Mexican War (1849, Benjamin B. Mussey & Co., Philadelphia).

Grant, Ulysses S. “The Complete Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant” (reprint 2009, Create Space).

Lopez y Rivas, Gilberto, “Septiembre de 1847: resistencia popular a la ocupación estadunidense” (La Jornada, 13 September 2024).