We don’t need another hero…

Reading for today: Chris Hedges, “We All Must Become Zapatistas” (TruthDig).

Subcomandante Marcos, the spokesman for the Zapatistas (Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional, or EZLN), has announced that his rebel persona no longer exists. He had gone from being a “spokesman to a distraction,” he said last week. His persona, he said, fed an easy and cheap media narrative. It turned a social revolution into a cartoon for the mass media. It allowed the commercial press and the outside world to ignore traditional community leaders and indigenous commanders and wrap a movement around a fictitious personality. His persona, he said, trivialized a movement. And so this persona is no more.

“Marcos” was always an over-covered figure, and as a non-Indigenous Stalinist, the media fixation on him did more harm t

han good to the movement.

Early Jan. 1, 1994, armed rebels took over five major towns in Chiapas. It was the day the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) came into effect. The EZLN announced that it no longer recognized the legitimacy of the Mexican government. It denounced NAFTA as a new vehicle to widen the inequality between the poor and the rich, showing an understanding of free trade agreements that many in the United States lacked. It said it had resorted to violence because peaceful means of protest had failed. The Mexican government, alarmed and surprised, sent several thousand members of the military and police to Chiapas to crush the uprising. The military handed out food to the impoverished peasants. It also detained scores of men. Many were tortured. Some were killed. There were 12 days of heavy fighting in which about 200 people died. By February the Zapatistas, who had hoped to ignite a nationwide revolution and who were reeling under the military assault, agreed to negotiate.

While I’m not the Zapatista’s biggest fan (there are huge problems with concensus governance when it comes to personal rights), their critique of consumerism and globalism (which means screwing most of the world for the benefit of those who already had more than enough) has been sorely overlooked.

The focus had to remain on dismantling the system of global capitalism itself. The shift from violence to nonviolence, one also adopted half a world away by the African National Congress (ANC), is what has given the Zapatistas their resiliency and strength….

[…]

This transformation by the EZLN, chronicled in some astute reporting by the Mexican novelist Alejandro Reyes, is one that is crucial to remember as we search for mechanisms to sever ourselves from the corporate state and build self-governing communities. The goal is not to destroy but to transform. And this is why violence is counterproductive. We too must work to create a radical shift in consciousness. And this will take time, drawing larger and larger numbers of people into acts of civil disobedience. We too must work to make citizens aware of the mechanisms of power. An adherence to nonviolence will not save us from the violence of the state and the state’s hired goons and vigilantes. But nonviolence makes conversion, even among our oppressors, possible. And it is conversion that is our goal.

Hedges misses the point that Marcos was the wrong person to deliver the message, but does catch that the message itself is what we need.

The last of the Montezumas

Thanks to a footnote in Alexander von Humbolt’s Political Essay on the Kingdom of New Spain — in a discussion of politics of water drainage systems over the centuries (one reason I like Humbolt is the guy was interested in … well… everything) I learned something new. The water drainage discussion came right after his statistical analysis of meat consumption, compared with that of Paris… concluding Mexicans ate more meat than the French, by the way) . Cuauhtemoc was not the last of the Aztec royal family to rule what is now Mexico.

While I had always been aware that up until 1611, there was a Caicique from the Montezuma family nominally ruling the “Indian subjects”, they never really had any political power, or any say in policy. But… a Montezuma by marriage did.

The first wife of José Sarmiento Valladares, the 32nd Viceroy of New Spain, was María Jerónima Moctezuma y Jofre de Loaisa, the great-great grand-daughter of Moctezuma Xocoyotzin. After her death in 1692, Sarmiento assumed the title of Condes de Moctezuma. His appointment as Viceroy in 1696 may have owed more to having the Grand Inquisitor for a brother, but the title didn’t hurt any.

The first wife of José Sarmiento Valladares, the 32nd Viceroy of New Spain, was María Jerónima Moctezuma y Jofre de Loaisa, the great-great grand-daughter of Moctezuma Xocoyotzin. After her death in 1692, Sarmiento assumed the title of Condes de Moctezuma. His appointment as Viceroy in 1696 may have owed more to having the Grand Inquisitor for a brother, but the title didn’t hurt any.

He was, by all accounts, an unusual viceroy (besides being cross-eyed), entering his realm incognito, had himself sworn in by the Audiencia (supreme court) in the middle of the night and took up his new duties, probably to the relief of the acting viceroy, the Bishop of Michaocán, Juan Ortega y Montañés, who had reluctantly taken up the job when the thirty-something viceroy, Gaspar de la Cerda quit in the middle of a plague (which, incidentally killed Sor Juana Inez de la Cruz) and student riots. While Bishop Ortega had managed to contain the riots, he left the clean up to the count of Montezuma, who used his title to at least claim he could speak for the Mexicans of Mexico, and was a relatively progressive adminstrator, expanding Spanish control north into what is now California, putting down banditry and reforming the Mexico City government. It was to the Count of Montezuma who divided Mexico City into “barrios”, the beginning of what is now the Capital’s colonias and Delegaciones divisions. He championed Mexican born artists and architects in his extensive public building campaign.

What seems most amazing is that the Count of Montezuma was appointed to his post by Carlos II… also known as Carlos the Bewitched, Carlos the Unfortunate, and Carlos the Butt-Ugly. The last of the Hapsburg Spanish monarchs, Carlos was the product of centuries of inbreeding… thought as a child to be retarded (he wasn’t toilet trained until he was in his early teens), physically deformed and possibly impotent. He wasn’t known for making good decisions, but then… he often wasn’t capable of making any decisions, but whoever actually made the decision on who to appoint to the critical position of Viceroy of New Spain made a relatively decent choice, considering how badly the Empire was managed during Carlos’ reign. With the King’s death in 1700, the Count returned home, to take part in the War of Spanish Succession… which led to the Bourbon dynasty, who had very different ideas on how to administer the colonies.

What seems most amazing is that the Count of Montezuma was appointed to his post by Carlos II… also known as Carlos the Bewitched, Carlos the Unfortunate, and Carlos the Butt-Ugly. The last of the Hapsburg Spanish monarchs, Carlos was the product of centuries of inbreeding… thought as a child to be retarded (he wasn’t toilet trained until he was in his early teens), physically deformed and possibly impotent. He wasn’t known for making good decisions, but then… he often wasn’t capable of making any decisions, but whoever actually made the decision on who to appoint to the critical position of Viceroy of New Spain made a relatively decent choice, considering how badly the Empire was managed during Carlos’ reign. With the King’s death in 1700, the Count returned home, to take part in the War of Spanish Succession… which led to the Bourbon dynasty, who had very different ideas on how to administer the colonies.

Mexico would have another Hapsburg ruler… as incompetent as Carlos II, but not quite as ill-favored, but never another Montezuma.

For a few pesos more…

Bellasario Dominquez, a Chiapas doctor and Congressman, publically denounced the 1913 U.S. sponsored coup against democratically elected president Madero for imposing a tyrannical dictatorship on the country. Tyrannical dictator Victoriano Huerta sort of took umbrage to that, and had Dominguez shot. Dominguez lived well, died (relatively) young, and left a beautiful coin behind.

At last that’s the assessment of the world’s mint directors, who at their 28th annual conference yesterday, held at the Mexico City mint (which has been in business since 1535, thank you very much) voted the Bellasario Dominguez commemorative 20 peso piece the world’s most beautiful circulating coin.

Nothing really to add… this says it all about “poverty tourists”.

I’ve long been a critic of favela tours, for any number of reasons, few of which are likely unique: it objectifies the poor; it is voyeuristic; it reinforces a so-called “First World”/“Third World” dichotomy that objectifies both the poor and those in “developing countries” (a term as loaded and barely better than “Third World”); it fails to connect local poverty to broader global issues and economics, many of which implicate the tourists themselves, directly or indirectly; it rarely provides tourists an opportunity to hear the voices of those who live in the favelas, instead relying on tour guides to “interpret”; and they fail to connect local poverty to broader national and global systems that allow for such poverty to exist and that often implicate and involve the tourists themselves, be it directly or indirectly.

In an attempt to perhaps placate and alleviate some of the guilt the (relatively wealthier) tourist…

View original post 2,178 more words

AHOY!

150 years ago, Maximiliano and Carlota came ashore on Mexican soil. The drawing is… shall we say… idealized? In reality, Max — being an admiral in the Austria-Hungarian Navy — in command of the landing craft, managed to run aground on the beach where the French army had been haphazardly burying troopers who had died of yellow fever.

In retrospect, making his entrance amid corpses, was a fitting start for that regime.

Defrocked delinquent disappears!

A new twist in the already twisted tale of Eduardo Cordova Bautisa… the defrocked priest whose pedophilia was said to have been covered up by the political and clerical elites of San Luis Potosí.

He’s disappeared and is now a fugitive from justice.

Next question… who helped him escape?

Un-chosen people? The Jews of San Juan la Laguna

[additions and changes as of 31 May 2014 in italics… with strikeouts of deleted material]

As reported in Voz Iz Neias? (an Orthodox Jewish news site):

Misael Santos, a convert to Judaism, has lived in San Juan La Laguna for six years and says for the past six months he, his family and other Jewish residents have experienced verbal abuse and racist insults from the community. The anti-Semitism reached heights when community members requested the approximately 30 Jews leave the village.

Mayor López ordered a Jewish registry to be created, said Santos, allegedly to keep note of tourism in the town, but the Jewish community became wary of the registry and the reasons behind its creation. That, in addition to physical violence – including stoning and throwing explosive devices – against Jewish community members sparked the investigation against the mayor.

San Juan la Laguna is a community of about 4000 divided into a various k’iche and tz’utujile speaking neighborhoods. One can assume that Mayan communities in Guatemala follow roughly the same social patterns as those across their northern border. As such, they are traditional communes as much as modern political units, managing to incorporate imported concepts (like elective mayors and political parties) on their own terms. Even in minor things like clothing, there tends to be a consensus on what is, and isn’t worn, even if members of the community are wearing non-traditional, “western” garb.

Religion — being essential to identity — is seen as communal, with religious dissenters often viewed as a threat to the value system of the entire people. While innovations, accepted by the entire community, are permitted, dissent is not. But, rather than resort to bloodshed, the dissenters are generally asked to leave, or driven out.

In Mexico, such communities are covered under the constitution by a guarantee that they may continue their self-goverance through traditional “usos y costumbres”. This creates some anomolies in the law… Oaxacan communities that vote by consensus despite other constitutional guarantees of a secret ballot, or in property rights cases (in one, a woman from the community lost her land, after obtaining a divorce in the United States and marrying an outsider without community approval). Still, there have been a series of incidents in which religious dissenters have been harrassed and forced to flee… often Protestants. Typically, a dispute starting with Protestants objecting to paying for an annual fiesta honoring a patron saint — either because they are teetotalers and see the fiesta as an excuse to get drunk (which they usually are), or because it’s a “Catholic” ritual — escalate into things like cutting off the dissenters from the community electrical system or occasionally violence against the dissenting family.

Although Guatemala, like Chiapas is about 40% Protestant, Protestantism is often seen as a foreign import, specially a U.S. import, making Protestants suspect as sell-outs to foreign interests, or the pawns of outsiders. Which is sometimes true. And although reported in the foreign press as a political dispute, much of the violence in Mayan communities is, at heart, religious.

While there are a few traditional Jewish Indigenous communties, and I know of one Islamic Mayan community, Jewish Mayans are new to me.

[added 31 May 2014: “Guanaguare”, written by a M.t. Levi Greer Walker of Panajachel, Solola, Guatemala, has two posts on this community that paint them in quite a different light than I do. Posts here and here] Mr. Santos, the Mexican convert who moved to San Juan from Mexico Guatemala City is presumably somehow related to the k’iche or tz’utujile community [although Greer Walker says only that he is Guatemalan and had a Jewish grandparent . Several foreigners, initially from Mexico, but later from Canada, Israel, Bulgaria and elsewhere joined him, again according to Greer Walker]. Besides being a foreigners, and dressing in a way that would stand out in this community (the San Juan Jews apparently are members of Lev Tahor, an ulta-Orthodox group that in trouble with Canadian authorities and seeking to move to Guatemala)*, they seem to have become a tourist attraction. As Tova Dvorin writes in Arutz Sheva:

Santos and one other Jewish family moved to the small town from Mexico city about six years ago, he said. But trouble really began after he began a synagogue, drawing Israelis and Jewish tourists alike to the Guatemalan heartland.

“About seven months ago, visitors came to celebrate the Jewish New Year here,” he stated. “A Mexican family stayed for five months. Were only two families in all, but then a public official began showing signs of discontent with the people here.”

How much experience the community had with foreign tourists is left unsaid, but apparently, the customs of the foreign Jews, or rather, the quasi-religious tourists coming to visit this small community (and possibly to emigrate) were seen as insulting by the local community:

The Times of Israel’s Natalie A. Schachar writes:

… [San Juan] mayor Rodolfo López told The Times of Israel on Tuesday. “But every community, and especially ours, as indigenous Mayans, has very special customs and traditions and we have to defend our rights.”

Residents have filed complaints with the municipality that the community of ultra-religious Jews have used a public body of water as a mikveh (ritual bath), practiced unhygienic rituals like kaparot (where a chicken is swung around a rabbi’s head before being slaughtered), and made disparaging comments about immodesty to tourists.

According to the mayor, the indigenous population has also been suspicious since a Canadian couple accused of child abuse reportedly moved to San Juan La Laguna with their six children.

Interstingly, The Times of Israel story’s link reads not “Residents …want Jews to leave” but

“Is a small guatemalan town expelling its jews”… suggesting to me that the story was changed after its first posting, and the most sensationalist claims are being questioned. Most foreign reports begin with the claim that the Mayor ordered Jews to register with his office… which does sound “pogramish”… but apparently was just that the mayor was checking immigration papers of the outsiders coming into his “Mayan” town. Given Lev Tahor is being investigated in Canada for “child abuse and neglect, psychological violence, forced marriages of underage girls and not complying with the required nationwide school curriculum”, and the Canadian authorities have been in contact with Guatemalan authorities regarding some Lev Tahor members wanted for various crimes in Canada, the mayor’s request seemed reasonable [Assuming the new residents of San Juan ARE Lev Tahor. If they are simply being tarred with the same brush, being assumed to be connected with the shadowy “cult”… but nothing that would change my thesis that the reported anti-Semitism is not at the heart of the reported incidents, but rather the by-product of the deep distrust within traditional communities towards outsiders].

It may have been badly reported, or the mayor may have actually used the words “all Jews must register” (or something similar, perhaps in K’iche) and perhaps the reported anti-Semetic harrassment that followed (according to the Orthodox papers, including fliers calling for the expulsion of “Christ killers,” the usual references to Hitler and stones being thrown at Lev Tahor migrants, followed by reports that the Mayor is being indicted for “inciting genocide”) are true… anti-semitism isn’t unknown in Latin America… but it may be overblown (or, given Lev Tahor’s reputation, completely bogus) reactions to what seems less and less another example of a conflict between traditional “usos y custombres” and religious dissent, and more a case of a small town finding itself inundated with unwanted guests.

* It should be pointed out that for some Jews, Lev Tahor is considered Jewish in the same way that Baptists think about Westboro Baptist Church: i.e., a fringe group that gives the religion a bad name.

Sources:

Tova Dvorin, Small Guatemalan Town Uses Nazi-Esque Tactics to Expel Jews” Arutz Sheva (26 May 2014)

Natalie A. Schachar, “Residents of small Guatemalan town want Jews to leave,” The Times of Israel, 28 May 2014

“San Juan La Laguna – Guatemalan Officials Open Investigation Against Mayor For Inciting Violence Against Jews“, Voz Iz Neias? 28 May 2014

“San Juan La Laguna” (Wikipedia)

Karla Zabludovsky, “Members of a Jewish Sect Lev Tahor Flee Canada for Guatemala” Newsweek, 31 March 2014

(and previous Mexfiles posts)

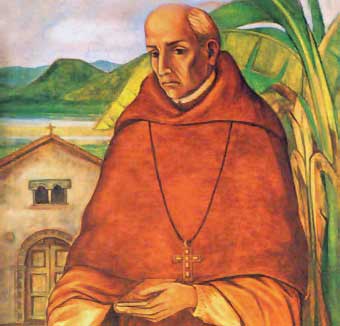

The active señor citizen… or Heaven can wait

Seems to be my night for catching up on the Catholic Church, and on the Catholic Church trying to catch up. Only about 450 years after the P’urépecha (Tarascans) of Michoacán came to the decision that Vasco de Quiroga was a true Saint, the Church has finally gotten around to considering, maybe, thinking out making it official.

Born in 1470, Don Vasco had a long and distinguished career as a judge and legal scholar in Spain, when in 1530 he was tapped to assist in setting up a proper legal system in New Spain. At age 60 — elderly by the standards of the time — Quiroga had already planned his retirement… as a high-level civil servant with a good pension and who had saved for his retirement, Quirga’s plan had been to continue with an “active senior lifestyle” in one of the better “assisted living centers” of 16th century Spain… it just happened to also be a monestery. Named Oidor de la Audiencia (Justice of the Appeals Court), Quirgo arrived in Mexico City in 1531, pension in hand.

While “active seniors” who move to Mexico normally expect their pension will last much longer in Mexico than at home, Quirga managed to go through the savings quite rapidly. But … as the first in a long line of seniors who, rather than retire, find a new career in Mexico, he spent it quite wisely. With a shortage of judges in the new colony, he was spending much of his time hearing normal minor criminal cases… petty thefts, brawls, muggings. He noticed that most of the defendants had two things in common… they were Indians, and they were drunk. Drunk Indians vastly outnumbering elderly Spaniards, there was a use for that pension money… setting up the San Cosme y Damiano Hospital, the world’s first alcholism rehab center… and giving Quiroga a teeny footnote in judicial history as the first judge to be be able to offer rehag in lieu of jail or fines.

But he was just getting started on his new career. From 1533 to 1537, he was also responsible for legal adminstration in the new province of Michoacán, where he learned P’urepecha, and — as the best of active seniors have done since — immersed himself in the local culture. When he finally did decide to go to a monastery… it wasn’t to retire, but to get himself ordained. While the State was able to bring in adminstrators, the Church was still struggling just to find clerics who could learn indigenous languages and preach a coherent sermon. Being a Bishop isn’t all that different from any other kind of administration, so being fluent in P’urepecha, immersed in the local culture and willing to take the job, he became the first Bishop of Michoacán in 1537, at the ripe old age of 67.

But he was just getting started on his new career. From 1533 to 1537, he was also responsible for legal adminstration in the new province of Michoacán, where he learned P’urepecha, and — as the best of active seniors have done since — immersed himself in the local culture. When he finally did decide to go to a monastery… it wasn’t to retire, but to get himself ordained. While the State was able to bring in adminstrators, the Church was still struggling just to find clerics who could learn indigenous languages and preach a coherent sermon. Being a Bishop isn’t all that different from any other kind of administration, so being fluent in P’urepecha, immersed in the local culture and willing to take the job, he became the first Bishop of Michoacán in 1537, at the ripe old age of 67.

And only getting started. Keeping up with new ideas is something always recommended to keep you young, and it being the Renaissance and all, new ideas were all around… just kind of slow reaching outposts like Michoacán. But a new best seller by an English author did fall into Quiroga0s hands… Utopia, by Thomas More.

More’s fictional island of Utopia is said to be somewhere in the “New World”, a place where “there is no private property”… a concept common to Quiroga’s P’urepecha neighbors, and a cause of endless friction with (and outragous depredations by) his fellow Spaniards, including those of the clerical persuasion.

As in Utopia, the P’urapechas lived mostly in rural communes, farming for the most part, though practicing trades useful to any peasant society… weaving, carpentry, metalsmithing, building. With a rather simple life (especially considering their elites had either been eliminated by the Spanish, or had adopted a Spanish lifestyle if they survived) there was an egalitarian simplicity… ripe for the pickings of greedy Spanish conquistadores looking for peasants to work lands they could grab from unarmed, defenseless farmers.

But, to Quroga, what this meant was that the P’urapechas were very close to the ideal Christian community dreamed of by the English writer. As to defenses, nothing better than a good lawyer… and he knew the best one in Mexico: himself. One the one hand, as Bishop of Michoacán, he saw his duty as “christianizing” the P’urepecha… whose lifestyle was already very close to the “ideal” Christian community. Oh, More said they needed priests (and that’s what Bishops are supposed to provide) and they needed education (that’s what the priests are supposed to be doing anyway… though adding the thoughts of Thomas More, and some practical lessons in Spanish business practice wouldn’t hurt as additions to the usual Bible study wouldn’t be stretching things too much) and they needed good contracts with the Crown.

Since, in the Utopian culture, everyone worked, Quiroga expected he would too.. writing those contracts (many of which have stood up for over four centuries) and organizing the details. The Utopian world was more than just communal and Christian. It was a world

… with goods being stored in warehouses and people requesting what they need. There are also no locks on the doors of the houses, which are rotated between the citizens every ten years. Agriculture is the most important job on the island. Every person is taught it and must live in the countryside, farming for two years at a time, with women doing the same work as men. Parallel to this, every citizen must learn at least one of the other essential trades: weaving (mainly done by the women), carpentry, metalsmithing and masonry. There is deliberate simplicity about these trades; for instance, all people wear the same types of simple clothes and there are no dressmakers making fine apparel. All able-bodied citizens must work; thus unemployment is eradicated, and the length of the working day can be minimised: the people only have to work six hours a day (although many willingly work for longer). More does allow scholars in his society to become the ruling officials or priests, people picked during their primary education for their ability to learn. All other citizens are however encouraged to apply themselves to learning in their leisure time.

While implementing some of the program was high-handed (people didn’t want to move every two years, and while they accepted wearing pretty much the same clothes, there are always those with a fashion sense, or a touch of rebellion who want to be slightly different… and fashions change for no reason at all), what made the experiment a success … and one that lasted for centuries… was that the P’urepecha were consulted about what could and couldn’t be done, and how best to do it.

More’s idea of “simple” crafts wouldn’t work in a community that, unlike the mythical Utopia, was not an island separated from the rest of the world, but surrounded by outsiders with money and resources the community lacked. So… the P’urepecha villages were organized to produce export goods… musical instruments in one town, pottery in another, clothing in yet a third and so on. In addition to creating exports and bringing in outside goods, it also meant the community as a whole was mutually dependent and had a cultural cohesion not found in other indigenous communities that were more easily assimilated or marginalized.

Quiroga, too busy to retire, was active up until he died at what was then the incredibly old age of 95… almost literally in the saddle (he was on a pastoral visit to Urupan). Called “Tata” (father) by the P’urepecha, he has been seen as a saint since… and while one might question the validity of some of the innumerable miracles attributed to him since he died, that he pulled off a few while he was still alive might just make qualify him to be not just the unofficial patron saint of Michoacán, but perhaps the ideal patron saint of expats everywhere.

Sources:

Richard Grabman Gods, Gachupines and Gringos, Editorial Mazatlan (2008).

Thomas More, Utopia, 1516.

“Vasco de Quiroga” Biografías y vidas (accessed 27 May 2014)

Rodrigo Vera, “Inician proceso de canonización de Tata Vasco” (Proceso, 1 May 2014).

Wikipedia, “Utopia (Book)” (accessed 27 May 2014).

Holy orders and court orders

This billboard, which appeared in San Luis Potosi two weeks ago, was the metaphoral lance that opened a huge boil in the side of the Mexican Catholic Church. The billboard features a photo of suspected pedophile Eduardo Córdova, and urges his victims to file criminal charges. There was no indication of who paid for the billboard and Cordova, at the time, was still a parish priest in the Diocese of San Luis Potosí. The State Prosecutor’s office claimed no criminal complaints had been filed against then Father Cordova, although Archbishop Jesús Carlos Cabrera Romero took the unusual step of opening church files related to Cordova to State investigators.

Within days, more than 100 cases of probable molestation were received by the prosecutors office, and a former priest who worked in the Chancellory came forward with claims he had covered up Cordova’s crimes in the past, assisting in his transfer from parish to parish ahead of “scandals”. Explosively, the former priest, Alberto Athié Gallo, claimed the state governor, Fernando Toranzo Fernández and his wife, had both participated in the coverup.

The Diocescan press office called a news conference to announce that Cordova was being defrocked, in itself an indication that seemed at first to suggest they were simply going to cut Cordova loose, by way of damage control. However, a team of lawyers representing fifteen working class families, not trusting that the those who covered up for Cordova (within the Church and within the PRI and the local establishment), have managed a “work around” : forcing the prosecutor’s office to name the Archbishop and his two predessors as co-conspiritors in a coverup.

This won’t be the first time members of the hierachy have been defendents in criminal cases. Cardinal NOrberto Rivera was forced to testify in a California court in a case also involving the transfer of a pedophile priest, but his testimony was limited to a deposition, and he never had to face any charges. Onesimo Cepeda, who had recently retired as Bishop of Ecatepac, was accused of fraud by the powerful Azucarraga family in connection with his role as executor of one family member’s large estate, and was arrested, but — given his ties to the establishment (including his accusers) — the charges were quietly dismissed and apparently the issue was resolved privately.

Given that this is a Mexican court, where the archbishops are co-defendants, and that there is less likelihood of a private settlement … and the Vatican itself has indicated it is willing to cooperate with legal authorities in these kinds of cases… there is every chance their Excellencies will have to answer in a public courtroom… and name names. I tend to think the latter is much more important than any punishment the court might mete out to the Archbishops. They are very unlikely to go to jail, and — thanks to Benito Juarez — the Church really doesn’t have the deep pockets to pay out huge fines (it doesn’t really own any property of note), but putting the hierarchy in a position where they have to chose between saving their own skins, or ratting out the establishment, the cozy relationship between church and state will be sorely taxed.

And, perhaps more importantly, the Church is starting to realize it needs to be more proactive. It’s not easy for some, but even the often clueless “Padre Beto” seems to be getting the message:

Sources:

Sin Embargo:

La sociedad civil contra el arzobispodo de SLP, A SOCIEDAD CIVIL CONTRA EL ARZOBISPADO DE SLP, Sanjuana Martínez, 27 may 2014

Animal Politica:

Denuncian ante PGR a sacerdote por más de 100 casos de abuso sexual en SLP, 13 May 2014

Catolicas por el Derecho a Decidir:

Catolicados, Capitula 12: “Una iglesia no amparo los criminales”

Genetic Pollution

Sorry to be mostly just doing cut and pastes today. I’ve been tied up with other things and have had to neglect this site for a time.

Via Truth Out and Triple Crisis:

To listen to the current debates over the controversial requests by Monsanto and other biotech giants to grow genetically modified (GM) maize in Mexico, you’d think the danger to the country’s rich biodiversity in maize was hypothetical. It is anything but.

Studies have found the presence of transgenes in native maize in nearly half of Mexico’s states. A study of maize diversity within the confines of Mexico’s sprawling capital city revealed transgenic maize in 70 percent of the samples from the area of Xochimilco and 49 percent of those from Tlalpan.

Mexico is the “center of origin” where maize was first domesticated from its wild ancestor, teocinte. The country is arguably the last place you’d want to risk the possibility that its wide array of native seeds might be undermined by what indigenous people have called “genetic pollution” from GM maize.

(read the entire article, “Mexico and Monsanto: Taking Precaution in the Face of Genetic Contamination,” Timothy A. Wise, here or here.

Become a witch-doctor in your spare time!

Well, sorta (and consider the source):

The University of New Mexico is going to offer a free online class on curanderismo — the art of traditional healing.

The school announced this month it will host the Massive Open Online Course as an offshoot of its popular curanderismo class offered on campus every summer.

Eliseo “Cheo” Torres, vice president for student affairs, said he will teach the class along with traditional healers from Peru, Mexico and New Mexico. He said the healers will show how traditional medicine is widely used among indigenous populations in the Americas.

Curanderismo is the art of using traditional healing methods like herbs and plants to treat various ailments. Long practiced in indigenous villages of Mexico and other parts of Latin America, curanderos also could be found in parts of New Mexico, south Texas, Arizona and California. In recent years, some curanderos have been found practicing in New York and in Georgia as immigration from Mexico has expanded into that areas.

Anthropologists believe curanderismo remained popular among poor Latinos because they didn’t have access to health care. But they believe the field now is gaining traction among those who seek to use alternative medicine.

Among the ailments curanderos treat are mal de ojo, or evil eye, and susto, magical fright.

Mal de ojo is the belief that an admiring look or a stare can weaken someone, mainly a child, leading to bad luck, even death.

Susto is a folk illness linked to fright experience like an automobile accident or tipping over an unseen object. Those who believe they are inflicted with susto say only a curandero can cure them.

“Curanderismo is so diverse now,” said Torres. “It is evolving.”

Death Girl

Raymundo Amezcua (Los Amigos del Arte Popular) posted this photo frm Michoacán taken in 1917 of his great-grandmother’s funeral. While photographs of funerals, and of the corpse, were not unusual in the 19th and early 20th centuries, Amezcua writes “This image and the memory led me to make my work and look death with a more festive such as the Day of the Dead sense.”

A celebration of the tragic… the family … and the persistance of memory… if that’s not the “real Mexico”, I don’t know what is.