The Revolution is out there…

It is one of the strangest facts of a strange country that the Mexican Revolution was rooted in ghosts. Not in a metaphorical sense, but in the very real one. Or, so it would seem, if once considers that Francisco I. Madero — scion of one of the wealthiest, and most privileged, dynasties in 19th century Mexico — found the courage to rebel against the system, bucked up by ghostly visitations from the dead heroes of the past.

Madero was an unusually gifted man… not only extremely wealthy, but unusually well educated (he attended the Sorbonne, as well as the University of California. Like many of his peers among the Latin American elites, he looked to France for his intellectual inspiration, but not the France of the Positivists (with their mix of English Utilitarianism and French logic, with a dash of Social Darwinism and Eugenics tossed in for leavening), but the France of the “new agers” (or rather, very old agers)… who — in the very French way, rationalized — a mixture of Hindu thought and early explorations of the new science we today call “psychology”. And, a lot of seeming nonsense… like receiving messages from beyond the grave. But it did lead Madero to think of revolution, and to produce one of the most under-rated, and powerful books of the 20th century. Not for its literary style (as Justo Sierra — the most intellectual of Don Porfirio’s “cientificos” would note,the danger was precisely that the book was not “literary” and could be understood by the under-educated masses) but for leading to one of the great social revolutions of the modern era.

Spiritualists were not necessarily superstitious cranks — it was a respectable movement in the late 19th and early 20th century that had attracted serious thinkers especially in France and the United States. The spiritualists felt they had scientific proof that the long dead could communicate with the living. Madero’s wife would go into a trance and dictate what the ghosts told her. Madero, with his wife taking ghostly dictation, held long conversations about democracy ad government reform with his long dead brother Raúl. Raúl had died as in infant, but, apparently, the dead Raúl had landed a job as ghostly secretary to… Benito Juárez! Juárez had never shown any interest in Hinduism and had been dead for over thirty years. Why he chose Raúl Madero as his secretary in the afterlife (and why he was corresponding with Mrs. Madero) was something best left out of Madero’s book The Presidential Election of 1910.

(Gods, Gachupines and Gringos, page 224)

But, Madero DID write about his ghostly encounters in another book, Manual Espírita, published in 1911. Soon to be President of the Republic, and a revolutionary leader at that, the Manual Espírita was quietly published only for the esoteric community and under the pseudonym “Bhîma”.

While Madero’s “Spiritism” (not, as I wrote, “Spiritualism”, but more on that in a minute) was unknown, it was usually commented on in the snarky, half-apologetic terms I employed in Gods, Gachupines and Gringos, if it is mentioned at all. While Madero remains a national hero, conventional historians have tried to bury or at least minimize his “esoteric” beliefs, but, they were there, and scholarship demands we recognize them. Thanks to C.M. Mayo, the ghostly remains of Madero’s thoughts and beliefs are still with us today.

Mayo, an elegant writer with her own unusually broad interests (an economist of note, she also maintains a website on the Emperor Maximilian, wrote a fictional biography of Maximilian’s adopted — or kidnapped — heir, Agustín Iturbide Green, and a number of travel books and produces “podcasts” on subjects ranging from Marfa, Texas to how to promote one’s artistic bent) took it upon herself to translate Manual Espíritu, after running across a copy in the Madero papers in the Secretariat of the Treasury library. As a “forgotten” book, but of scholarly interest, Mayo took it upon herself to translate the “Spiritist Manual” for … shall we say… an audience of adepts (at Madero studies, that is).

Interesting, in an odd way, as the 90 page “Spiritist Manual” is, it is Mayo’s own story of how she came to translate the book, that hold you. The strange paths of research and scholarship it led her into that makes up the bulk of her own “Metaphysical Odyssey into the Mexico Revolution”.

Interesting, in an odd way, as the 90 page “Spiritist Manual” is, it is Mayo’s own story of how she came to translate the book, that hold you. The strange paths of research and scholarship it led her into that makes up the bulk of her own “Metaphysical Odyssey into the Mexico Revolution”.

While we think of Madero in purely Mexican terms, as a Mexican hero, fomenting a nationalist revolution, Mayo delves into the internationalist roots of his Spiritism and its effect on his eventual emergence as a revolutionary. From the Finger Lakes of New York, to the banks of the Ganges, by way of Czarist Russia with stops in Paris and London, Madero’s philosophy … Spiritism (“Spiritualism” doesn’t necessarily presume the dead can still contact us, and Mayo is particularly good at sorting out the different and often warring new philosophies of the era) we are embarking on a journey into the — not unknown, but forgotten — intellectual past. Mayo — who after all is a travel writer, among her several talents — is our guide on what is as much her own “Metaphysical Odyssey” as a journey down roads less traveled, but with one heck of an unusual view.

Like any good travel guide, she takes herself, and the landscape, in stride and with good humor, not afraid to note the “yucky chunks of cognitive dissonance” along the way. High scholarship doesn’t preclude comedy: Krishnamurti — to this day a somewhat overly-revered figure — comes across as a “sad eyed and androgynous looking person who seems to have dreamwalked out of a Francis Hodgeson Burnett-meets-Rudyard-Kipling-on-mushrooms fantasy.

Madero’s martyrdom colors our perceptions of courageous little man from Coahuila. That he was human, and perhaps a bit guillible (aren’t we all?) is less a miracle than something of a reminder that any of us can do great things, with or without advise from the other side. As to those visitors,

What these spirits actually were, whether of Mexican heroes, disembodied poseurs from the astral real, parts of Madero’s own psyche, or fantasy, or something else, is another question.

As Mayo notes in writing about herself, and how she came to write her book, every one of us knows extraordinary people, and while her own social connections — made her research easier, all of us are connected to the past, and in ways we don’t think much about, are talking with ghosts all the time.

C.M. Mayo, Metaphysical Odyssey into the Mexican Revolution: Francisco I. Madero and His Secret Book, Spiritist Manual (ISBN-13 978-0-9887970-0-0) Palo Alto: Dancing Chiva, 2014.

Ghosts!

I talk with my father when shaving in the morning and to my mother when making matzoh ball soup.

Both have much to say.

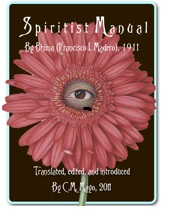

Warmest appreciation for this review. Readers might be interested to know that the cover of METAPHYSICAL ODYSSEY INTO THE MEXICAN REVOLUTION: FRANCISCO I. MADERO AND HIS SECRET BOOK, SPIRITIST MANUAL, is very different now, though it still features the painting “Eye and Gerbara” by San Miguel de Allende-based artist Kelley Vandiver.

It is now available in paperback as well as Kindle, and in Spanish in both formats as well.