A bridge to the 21st century

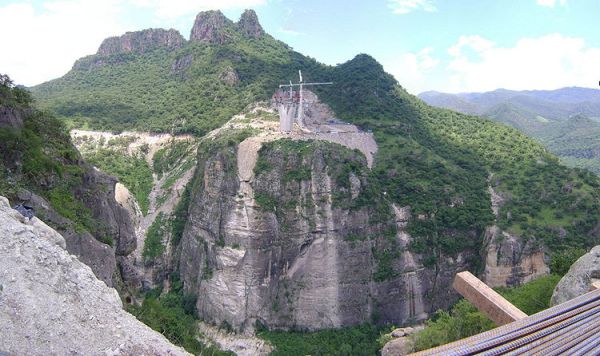

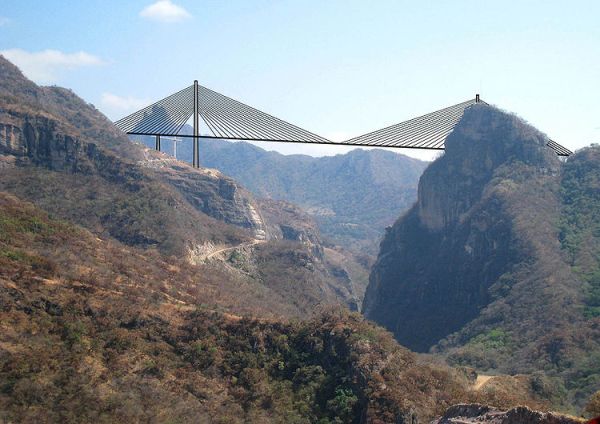

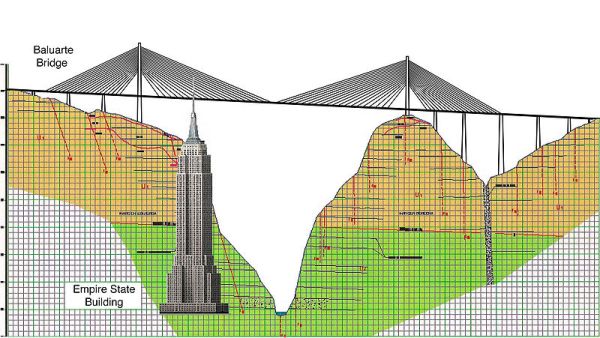

When it is completed in 2012, the Baluarte River Bridge will not only be the highest bridge in North America but the highest cable stayed bridge in the world surpassing the Millau Viaduct in France. It is the crown jewel of the greatest bridge and tunnel highway project ever undertaken in North America. Known as the Durango-Mazatlán highway, it will be the only crossing for more than 500 miles (800 km) between the pacific coast and the interior of Mexico. The path of this new highway roughly parallels the famous “Devil’s Backbone”, a narrow road that earned its nickname from the way it follows the precarious ridge crest of the jagged peaks of the Sierra Madre Occidental mountains. The dangerous road is a seemingly endless onslaught of twisting, terrifying turns that are so tight there are times the road nearly spirals back into itself.

By cutting a safer, more direct route through the mountains, the highway department of Mexico hopes to improve trade and increase tourism between the city of Durango and the coastal city of Mazatlán…

The “Devil’s Backbone” has traditionally cut off Sinaloa from central Mexico. The turn of the last century ethnographer and explorer Carl Lumholtz writes of burros falling off cliffs while negotiating what was then the best and safest link between the Sinaloa coast and the rest of the north. It’s the reason Mazatlán might be the closest seaport to a rich mining region, but its exports were mostly seafood and easily transportable local produce (like marijuana and opium) and it has never become a major import center (except maybe for tourists) and why, culturally, it often looked north to San Francisco or south to Guadalaraja, than east to Durango and Chihuahua.

Cutting a highway of any kind through the Devil’s Backbone in the 1940s was a tremendous engineering feat, matched only by the Copper Canyon Railway, not completed until the 1960s. But expanding traffic on that railroad is — while technically possible — probably not in the cards. Topolobampo, the port serving the railroad is too shallow for expanded container ships (and the seabed is basalt, making various proposals to deepen the port more than slightly unrealistic. Although rail traffic is more efficient and ecologically sound than truck traffic by a factor of something like 30 to 1 — not that I’ve looked it up lately, so don’t hold me to those numbers), it has always made economic sense to expand the Mazatlán-Durango highway.

Richard Rhoda and Tony Burton (Geo-Mexico) look at the probable economic impact:

…The driving time from Monterrey or South Texas to Mazatlán will be reduced to less than a day. This could revive Mazatlán as a major tourist destination after a couple of decades of relative stagnation.

Perhaps the biggest effect of the new highway will be the improved connection between the Pacific Ocean port of Mazatlán and north-central Mexico (population about 12 million) and most of Texas (about 20 million). The impact from increased trade in finished products (especially those which are relatively light and suitable for truck transport) will be significant.

Shrimp from Mazatlán and many, many products destined for northern Mexico/Texas from the Pacific Rim Region (China, South Korea, Taiwan, Japan, Indonesia, Australia, etc.) will be shipped through Mazatlán and trucked from there on the new highway. We expect there will be considerable trucking/shipping in the opposite direction as well…

We expect the impact on the state of Durango will be less. Most of Durango’s mineral and timber products are rather bulky, not ideally suited to truck transport, and not globally competitive; therefore they will not find their way through Mazatlán to world markets.

Rhoda and Burton note an article by Chris Hawley in the 26 April 2010 USA Today that fretted (as U.S. reporters are supposed to do) about possible effects on the narcotics trade. Certainly, easier access will mean that police and soldiers can reach the region (as the railroads did for large sections of Mexico in the late 19th century, making Porfirio Díaz’ efficient dictatorship possible). That may have some social impact — the isolation of the region being one of the prime reasons it has always had an “outlaw culture”… hills breed hillbillies. And the Devil’s Backbone is hillier than most inhabited places on the planet.

Of course Rhoda, Burton, Hawley and the engineers on the project cannot predict the social and cultural impacts. Travel the highway now (before the romance is gone) and you’ll see, off in the hollers (relatively close to the “civilization along the road) satellite schools … the only way to provide a decent education in the region being via satellite transmission. I’ve sometimes wondered what happens to those kids when they finish (IF they finish) their education. It’s a hard land to make a living in and a good road through is also going to be a good road out. Other than serving travelers (and perhaps assisting in the transport business), what those kids will do in a few years, how they will think and act — as independent, self-reliant dirt-poor mountaineers, or as cogs in the global economy — I don’t know. None of us do.

But, it’s going to be a cool bridge and will give a whole new meaning to getting high in Mexico:

¡Guao, Richard!

O tal vez ¡Guaou! Richard.

Gotta ask you a question. In 1951, members of my family, including me, took a trip down into Mexico. From El Paso we went through Chihuahua City to Durango City, across some mountains to Mazatlan (one and a half hotels there at the time), to Gaudalajara, Zacatecas and back to Durango before returning to El Paso and north to home. Did we cross that terrible mountain range you talked about in the bridge article? If so, I didn’t realize what a feat we had accomplished until reading your blurb.

Yep, you sure did J.C. Not only did you have to cross the Devil’s Backbone, it was still a dirt road across the top of the mountain!

Oh, I remember the dirt road part! And the apprehension everyone in the car felt when we met oncoming traffic, both gas powered and animal.

I remember the bus rides our family would take from Mazatlan to visit our relatives in Torreon. My mother would always pray and hold her rosary a little harder when going through the Espinaso Del Diablo as they would call it. I thought it was neat and loved the vistas completely oblivious, but a little carsick, to the dangers.

The bridge was inaugurated this week. The first of many across the Devil’s backbone.