Guardia Nacional: sausage making at its best

The most controversial of the new government’s proposals has been the creation of a “National Guard”. Previous administrations have danced around the constitutional ban on using the military for internal security here though “temporary” legislation, while AMLO, relying on mention of an undefined “national guard” in the Constitution had pushed for legalizing the military’s role in domestic policing though the creation of a National Guard.

Given the name, it’s easy to think of the National Guard in the United States… which is the Army for all practical purposes, although the individual units are under the control of their various state governors. While US National Guard unites are deployed as police units when there is civil unrest (and somewhere in Mexico there are always unrestful civilians), the model here is more something of a paramilitary police, like the Spanish Civil Guard, or the Italian Carabinieri: cops with more weapons, and a military command and control structure.

But while AMLO and his party control both the Senate and the Chamber of Deputies, they do not have the absolute majority they would need to force through Constitutional changes needed to get around the ban on using the military for police work (something previous administrations did through “temporary” legislation, claiming all those soldiers and marines running around the countryside were just “advisors” and assisting police… or… basically… by just ignoring the Supreme Court) and the various opposition parties did have decent arguments against the plan.

The main opposition came from those who questioned military control, something even military officers were reluctant to sign on to. Mexico, after all, was the first Latin American nation to de-militarize its political system (the only military man to serve as president since 1946 was Ruiz Cortones, who’d been a quartermaster during the Revolution, but that had been over 30 years prior to his election), and after the reputation of the military as the guardians of the Revolution took a massive hit in 1968, when they were obviously the agents of repression, the generals and admirals have been sometimes over-zealous in avoiding any hint that they were making policy decisions when it came to internal issues. During the “drug war” Peña Nieto’s Secretary of Defense, General Salvador Cienfuegos openly admitted that the Army was ill-prepared to handle internal security, and that it opened the Army to corruption and abuse. And, when it comes to abuse, the military has its own justice system. which would complicate any prosecutions for human rights abuses, or other criminal behavior, by the National Guard; would the guards be tried by civilian or military courts, and how would a civilian victim bring charges?

Peña Nieto had dissolved the Secretariat of Public Security, turning over policing the police to a National Security Council, which was de facto dominated by the Secretary of Defense. AMLO has restored the department, under a slightly different name and mission… Secretary of Security and Civilian Protection… charged not only with overseeing police, but intelligence operations and the penal system as well. In other words, crime and punishment. To lessen opposition to a national guard dominated by the military, AMLO proposed making the guard’s command a troika: the Secretaries of Defense (always a general), Navy (always an admiral) and of Security and Civilian Protection. However, the bill passed yesterday puts the guard solely under the civilian secretary. It doesn’t hurt any that the sitting secretary, Alfonso Durazo, is a civil engineer with a doctorate in public policy, and previously served in more pacific cabinet position, as Secretary of Social Development. It didn’t hurt with winning over the PRI senators that Durazo had been the all but canonized by his party Luis Donaldo Colosio’s private secretary during the assassinated PRI reformer’s presidential campaign.

While putting the Guard squarely under civilian control won over a good part of the opposition, there was also the legitimate concern that the Guard would just be another restructuring of the national police… something tried several times before, only to find the same corrupt and badly managed coppers just had new uniforms and a new name. The military, for all its faults, enjoys a relatively good public image as less corruptible, more disciplined, and … frankly… in better physical and mental condition to perform the dirty work of protecting the people.

To not lose the advantages of a military organization (and those in the senate who favor a more military approach to law enforcement), the National Guard bill calls for the Army and Navy to organize the Guard: setting the standards for discipline, organizational hierarchy, rules and regulations, fitness standards, and the like. To keep those senators who admitted there was a role for soldiers and marines in pursuing certain types of criminals (narcotics dealers, timber and oil theft cartels) but are reluctant to turn policing over to the military, the bill gives only a five year lease on life to the uniformed services having a role in the National Guard.

There are a few issues to be resolved… the lines between the existing Federal Police and the National Guard for one. In the past, when major new policies were implemented, the details were often left for later… or never… leaving the administrators free to make up their own rules, and carve out their own fiefdoms as the went along. Yesterday’s bill avoids much of this, setting firm deadlines for passage of secondary bills to deal with the things usually left behind, like funding levels, operational parameters, etc.

Passing legislation is like making sausage: no one want to know the details, 19th century German Chancellor Hindenburg supposedly said. But, of… when you get a controversial proposal through a legislature with NO opposition… it’s a piece of cake,

A break-through in Mexican journalism?

Maybe people power has finally breached the walls of Mexico’s premier snob-appeal rag, Hola, specialists in glamour shots of the rich and famous and just famous for being rich… with their first ever cover photo of an indigenous person.

Of course, they lightened her skin by about 40 percent, and photoshopped her body to conform more closely to European ideals… but hey… I guess it’s progress.

Hokey Smokes!

Bullwinkle J. Moose of Frostbite Falls, Minnesota may have been the All-American Moose, but his character was defined here in Mexico… Gamma Productions did the work not only for “Rocky and Bullwinkle” cartoons, but also TotalVision… producer of Tennessee Tuxedo, and other cartoons… throughout the 50s and 60s.

A symbol of the nation

Do you recognize this woman?

She is one of the most famous women in Mexico that you never heard of, though most Mexicans have seen her picture.

A Mexico city barmaid, Victoria Dorenlas was a teenaged widow, working as a barmaid in Mexico City, a bar frequented by, among others, the muralist Jorge Gonzáles Camerena, her sometime lover, and regular model at the end of the 1950s and early 1960s. What may not be his best work, but certainly his best know, was not a mural, but a 1959 oil painting, “La Patría”. For a generation, it graced the covers of all textbooks published by the Education Department, and still does for some, having become an instantly recognizable national icon.

As for Victoria herself, not much is known. She was born in San Augustín Tlaxco, Tlaxcala sometime in the 1940s (indigenous births were not always recorded), had been married in her early teens to a politician’s bodyguard, widowed by the time she was 19, and other than her relationship with Gonzáles, who received a state funeral when he died in 1980, nothing is known of Victoria’s later life. As a person, she disappears from history. As an icon, she IS History (and, for many… trigonometry, geography, and chemistry as well).

Angie Magaña, ¿Qué fue de la mujer que aparecía en la Portada de los libros de la Primaria de hace unos años?, Tuul, 4 January 2017

Mauricio Obleo, “¡Quién es Victoria Donrenlas, la imagine de los libros de texto?” La Silla Rota, 13 February 2019.

The Ten Tragic Days on film.

Posted on historian Joshue Ramirez’ “Facebook” page, this 1913 film (with narration added later) of the events of the Ten Tragic Days, was the work of pioneering Mexican film-maker Salvador Toscano (1872 – 1947).

The Ten Tragic Days (Spanish: La Decena Trágica) was a series of events that took place in Mexico City between February 9 and February 19, 1913, during the Mexican Revolution. This led up to a coup d’état and the assassination of President Francisco I. Madero, and his Vice President, José María Pino Suárez. Much of what happened these days followed from the crumbling of the Porfiriato system of repressive order giving way to chaos, and as such, these days’ events have been among the most influential of the Revolution’s history. Madero’s martyrdom shocked a critical portion of the population, and the unwelcome foreign intervention prepared the way for the growing nationalism and anti-imperialism of the Revolution. In many ways, then, it set the tone for the Revolution’s most violent period, but it also prepared the way for an agenda of profound political and social change.[1]

While the bulk of fighting occurred between opposing factions of the regular Federal army, the random nature of artillery and rifle fire inflicted substantial losses amongst uninvolved civilians.

Food, glorious food…

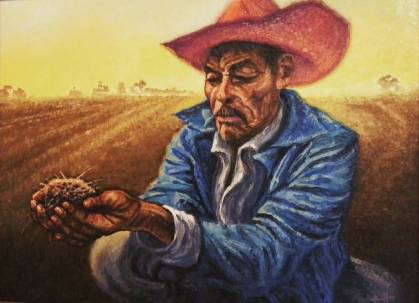

Painting by “artistraffi”

In an era when technology and globalization often seem to erase the lessons of the past, Mexicans’ deep consciousness of their history is striking. The Mexican Revolution in the early 1900s continues to be a source of pride and inspiration, and not just in monuments and holidays. The new agriculture plan references revolutionary leader Emiliano Zapata’s 1911 Plan de Ayala, which demanded comprehensive land reform and rights for peasant farmers. In 2018, more than 100 Mexican farmers’ organizations in the Movimiento Campesino (Farmers’ Movement) came together around a new vision—the 21st Century Plan de Ayala—that was endorsed and championed by then candidate López Obrador. The new Plan de Ayala outlines a series of demands on land reform, agricultural production, and public and environmental health, grounded in the rights of farmers, farmworkers, women, indigenous people and youth. Food sovereignty—the concept that agriculture should serve local communities first, based on local decision making—is at its heart. “In short,” the groups proclaim, “we need food and nutrition sovereignty to be public policy, based mainly on small and medium-scale agricultural production, with strategic planning and developed with full participation of both producers and consumers, and guided by agroecological criteria.”

It has been said that our new government is “radical”… in the sense of going back to our roots, perhaps it is.

More at: “Bold farm plans in Mexico offer a ray of hope in 2019” (Karen Hansen-Kuhn, Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy, 15 January 1019).

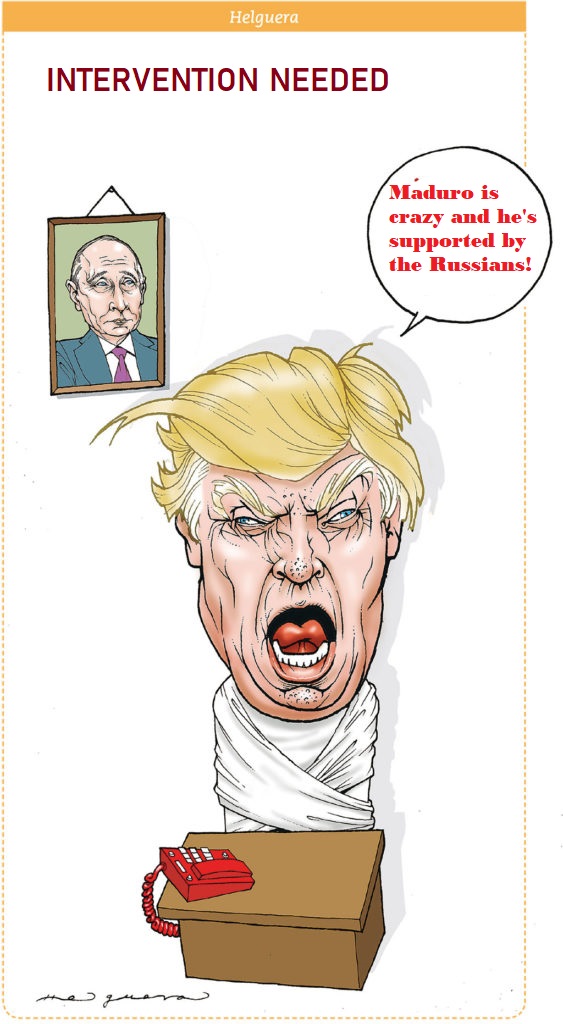

Helguera in this week’s Proceso

Why it matters: Venezuela and the rest of us (including Mexico)

John Ackerman in Proceso (4 de febrero, 2019)… my translation (and a nice companion piece to Plus ça-change: part 1, and the still to be written part 2)

When the word democracy is used to justify coups, the concept loses any semantic content. When the supposed defense of human rights is used as a pretext to strangle a people with hunger, cynicism becomes law. And when the supposed defense of popular sovereignty is mobilized as a motive to destroy national sovereignty, hypocrisy feels real.

Beyond a concrete evaluation of the political development of past or present situations and actions in Venezuela, yoking them to the supposed authoritarianism of the “Maduro regime” today implies being an accomplice to the dictatorial and interventionist actions of the United States and the old Euopean colonial powers.

Any discussion of the strengths and weaknesses of the political system and development model in Venezuela, or any country, should be sharply separated from a debate on foreign intervention in Latin America. Popular sovereignty is simply not possible without first having a strong national sovereignty.

If an economic crisis or mass migration were sufficient reasons to invade a foreign country for “humanitarian reasons,” Mexico would have been occupied for decades by some foreign force. And if the lack of freedom of expression were a justification for removing the leader of a nation, we would have to start with the overthrow of the King of Saudi Arabia, Salman bin Abdulaziz.

The last presidential elections in Venezuela took place eight months ago. Despite a 40 percentage advantage between the first and second place finishers, Washington has announced to its comrades in the old regime that it just occurred to them to denounce what it assumes were “electoral fraud”.

The last thing that these “democrats” are interested in is defending citizen rights and citizen power. They do nothing but parrots the Pentagon’s rhetoric and agenda. They speak and present themselves as “liberals”, but in reality they are abject slaves of the ideology of power and the status quo.

America’s next target?

But the most worrisome thing is that in their supposed concern for Venezuelan democracy these voices reveal their willingness to accept a possible coup d’état in Mexico. The same pundits and columnists who today find thousands of different reasons to overthrow Nicolás Maduro, will use the same reasoning to attempt to justify putting aside Andrés Manuel López Obrador.

The strategy of the United States in Venezuela is in charge of John Bolton and Elliot Abrams, two of the most authoritarian, intolerant, militaristic and hypocritical politicians in ever in the history of the continent. The long history of their positions and their actions in Latin America, and the rest of the world, show their absolute disdain for the rule of law and democratic processes (https://bit.ly/2RsA66D).

Likewise, the presumed “President in charge” of Venezuela, Juan Guiadó, also has a dark history of his own, with a long record of collaboration with American financing and ideological systems, as documented extensively by journalists Don Cohen and Max Blumenthal (https://bit.ly/2RSIbqx).

We can not afford any illusion about the democratic character of the regime that would follow an eventual overthrow or resignation of Maduro. Beyond what one can say for or against the democratic characteristics of the current government of Venezuela, we can be sure that any new regime imposed by Trump and his representatives would be totally authoritarian and exclusive.

This happened after the United States overthrew the democratic governments of Jacobo Arbenz in Guatemala in 1954 and Salvador Allende in Chile in 1973. Both countries had to suffer for decades under authoritarian and violent political systems after US interventions. Venezuela would suffer a very similar fate if Trump gets his way.

The debate is not between anti-imperialism and anti-authoritarianism. This is a false dilemma imposed by those who want to strengthen the narrative of American interventionism. The struggles against neocolonialism and despotism go hand in hand. Self-government is a sine qua non of democracy. So today all the citizens of this great American continent, from Alaska to Tierra del Fuego, are called to express together our strongest repudiation of the lastest theft of the dignity of the peoples of the South and to act accordingly.

Plus ça change… regimes (part 1 of 2)

Thinking, or perhaps obsessing, about the attempt at “regime change” in (not so socialist1) Venezuela, and yesterday being the 171st anniversary of the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo… a “regime change” of a rather permanent sort for at last half of Mexico, Vijay Prashad’s “Trump’s Venezuela playbook is disturbingly familiar: Here’s the 12-step American method for regime change” reminds us why the tactics used in destablizing and overthrowing Latin American (and other) governments really is so disturbingly familiar: they go back, not just to the 1970s, or post-World War II, but a good two centuries, at least as far as regime change goes in Mexico.

We usually hear of 12 Steps as a means to recover one’s lives… though in a way, the 12 steps Prashad notes are recovery of a sort: the recovery of control over the economic resources of their target nation. The first step, “Colonial Traps” as Prashad calls it, is — like the First Step of recovery programs — is recognizing the problem, or for the imperialist interloper, the opportunity. The former colonies of Spanish America were all dependent on exports, usually a single export. Although it was the hey-day of naked colonialism, perhaps their unfortunate experience in their 13 colonies in North America had convinced the British that there was a cost effective alternative to ruling an American country when all they wanted was American resources. At any rate, in 1825, as Britain was signing “friendship and free trade” agreements… usually brought by a warship bristling with cannons in the new nations’ harbors… Prime Minister George Canning observed “Spanish America is free,and if we do not mismanage our affairs she is English … the New World established and if we do not throw it away,” or… put another way… we don’t need to send an army (yet), there’s people there we can work with.

And they did. Henry George Ward, Britain’s first ambassador to Mexico, spent most of his time scouting out mining operations that had been neglected during the Independence Wars and were available cheap, as he was to other investment opportunities. His “Mexico in 1827” is largely a paean to the British owned mines then in production. The British did gain control of the mining industry in the early 19th century (and still, through their Canadian proxies, control about 80% of Mexican mining), despite some competition from France (their 1862 invasion was largely based on interest in obtaining mining concession in Sonora) and the United States. Although the first United States Ambassador, Joel Roberts Poinsett, was more interested in another commodity2 … land (specifically Texas) during his tenure (actively meddling in Mexican elections to sway the elites to support US goals), when oil became Mexico’s main export, it sought mightily to control the state and, though it, control oil production. Indeed, the Mexican Revolution only became a social revolution when the U.S. Ambassador, Henry Lane Wilson plotted to overthrow the democratically elected president and install a more “oil company friendly” dictator3. That it didn’t work out (although it cost Mexico another 7 years of civil war) only shows the need for going beyond the first step.

Prashad’s “Second Step” — Defeating the New International Economic Order — preventing the victim nation from “pivot[ing] away from the colonial reliance upon one commodity and diversif[ying] their economies” has been largely successful in Mexico… although that diversification has only meant more foreign ownership of Mexican resources (specifically human resources). That is, Mexico’s diversified industries are foreign owned, although the foreign governments do all in their power to ensure Mexican wages stay low and profits can be repatriated.

Historically, though, there are two earlier examples of Mexico attempting to get control over resources, and foreign pressure to prevent the change. Juarez’s government nationalized Church properties in 1859, giving France (as defender of the Papacy) another rationale for invasion. In the 1920s, as Mexico was trying to gain control, and collect revenue from the oil fields, the United States withheld diplomatic recognition until the Bucarelli Accords were signed, giving the United States “special rights” over oil production. When the Mexican government finally was able to gain control over its oil in 1938, there were demands for US and British military intervention, prevented only by the Second World War, although ever since, foreign governments and institutions, and Mexicans working in the interest of foreign actors, have done everything in their power to first weaken PEMEX and then to justify its privatization on the grounds that it is a weak company.

Step three — killing agricultural sufficiency, and impoverishing rural communities — has been a relatively recent phenomena. Only in hindsight was it realized that favoring industrialization (especially the “maquadora”… foreign owned… factories) over rural development would lead to a Mexico which exports luxury crops (winter fruits and vegetables, marijuana, coffee, sugar) while importing basic foodstuffs like beans and corn. And allowing Mexican food distributors to be bought up by foreign capital. NAFTA is largely to blame for this, agriculture being an afterthought to the neo-liberal (and mostly U.S. Educated) negotiators.

Step four — the culture of plunder — is self-explanatory. Ever since Hernán Cortes showed up “to spread the word of God, and make ourselves rich” stealing public goods has been encouraged. Poinsett only walked off with a few cuttings, while those who followed walked off with half the nation’s territory. Heck, the Illinois voluteers in 1848 walked off with one of General Santa Anna’s prothetic legs, and the thefts of artistic treasures and pre-Colombian artifacts has been incalculable. Is it any wonder that Mexicans themselves plunder? It is interesting to see that US media covers the attempts to stop small scale plunder (of gasoline) right now as if it were some quixotic quest by a slightly cracked President, and not just the first step (after recognizing the problem, that is) of plunder.

Step five — debt. This is the biggie. Mexico’s economy was shattered at independence, and, as George Canning realized back in 1825, the surest way of controlling the country without having to go to the trouble and expense of actually running the place. Both the French attempt to invade in 1838, and their massive invasion of 1862, were debt collection operations. Britain … which had the largest 19th century debt, managed to squeeze out all sorts of concessions (mostly for railroad rights) and, in the 20th century, the prospects of repayment of Mexican debt to U.S. Banks played more than a small role in several recent elections. That the United States is already showing hostility towards the new leftist administration, one is tempted to think, has as much to do with the prospect of the state actually getting control of its own finances, as with anything else.

Step six and seven— let public finances go to hell and cut social spending. Why, yes. The United States was ecstatic when Carlos Salinas “won” the presidency (with the assistance of the CIA?) and ushered in a more “neo-liberal” government, cutting social spending in favor of debt repayment and “tickle down” economics. Remember when Enrique Peña Nieto was going to “save Mexico”… the savings being mostly on the backs of the poor and needy. It’s an interesting side note that the Mexican reformers… those who wanted to give back to the people… have been painted as the villians in U.S. History: Pancho Villa, for example. Lazaro Cardenas was, if you read the “mainstream media” of the time, a dangerous Commie. As, so far mostly on the far right blogosphere, is Andres Manuel López Obrador.

Step eight — migration. At times of unrest, ´people migrate. Although there was a time when the people didn’t cross the border, but the border crossed them, those who found themselves in the other country were seen as interlopers, and a “problem” the more powerful United States needed to control… and another excuse to intervene. Lynching Mexicans and Mexican-Americans seemed to have been a popular sport in south Texas during the Revolution, and the exiled Cristeros were seen by the Coolidge Administration as not so much a problem for the United States, as they were useful as “victims” of the “evil” Mexican administration. That the Cristeros and other counter-revolutionaries were being financed and armed by U.S. Interests was something best left unsaid. Mexican migration… fueled by economic issues (largely exacerbated by cuts in social spending and agricultural collapse) has been successfully “spun” to discredit Mexican governments. It’s an interesting variation on the theme that migrants passing though Mexico from the Central American states… whose woes are directly attributable to U.S. Policies and interventions… has become the rationale for anti-Mexican rhetoric, and actions, by the Trump administration.

Part 2: Have we something to fear, or just fear itself?

1. “’Socialism of the 21st century’ was nothing more than a fraud. It was a farce made up of ‘socialism” in words, but the defense of capitalism in deeds—and not just any capitalism, but a rentier economy totally dependent on oil. In Venezuela, from every $100 that enter the country as foreign exchange, $97 is for oil, and the rest is for other minerals. Chavista “socialism” did not even develop national industries. Venezuela never stopped being a capitalist country.”

2. Not the flor de nochebuena, which he patented and named Poinsettia, though that too would be an example of foreigners stealing a local commodity for their own benefit, and leaving the producer with next to nothing.

3. Similar to what happened in Honduras in 2009, where Secretary of State Hillary Clinton justified the coup as “constitutional” the 1913 coup was given a fig leaf of credibility by claiming it was a “constitutional” change in government. Madero was forced to resign, the next in line for President being Pedro Lascaran, who stayed in office the 45 minutes it took to swear in Huerta as the next in line for the presidency, and then resign office.

There’s a sucker born every minute…

… and the US media seems to be full of them, if they believe what’s being sold.

Ramon Lobo, in El País (1 February 2019)

If the alternative to Nicolás Maduro, who has given ample evidence of his ineptitude, is John Bolton, we can only say, “poor Venezuelans!” Bolton was one of the architects of the lies of mass destruction on which the invasion of Iraq in 2003 was based. In politics, lying is corruption; it should permanently disable the liar, over and above any criminal sanction.

Iraq was an excellent business for US companies and oil companies, such as Halliburton, which Bolton seems to continue to represent. It was also a terrible business for the more than 400,000 Iraqis killed in the wars that followed the overthrow of Saddam Hussein. We could add the 500,000 dead of Syria, a conflict derived from the Iraqi chaos, and the sufferings of millions of refugees; not to mention the continued existence of ISIS and the outbreak of global xenophobia. Invading Iraq might be good for private enterprise, but it has not been for half the citizens in the world.

Bolton is the brains behind the two Venezuelan presidents crisis, or as they like to call it, the “subtle threat of intervention” (the 5,000 soldiers for Colombia scribbled on a legal pad). He also wants to bomb Iran, a more complex and dangerous target. In that case, he is recycling tricks from 2003, not hard in a world without memory. This week he had the nerve to speak on a program of Fox News about Venezuelan oil, how good it would be for US companies.

Vice President Mike Pence is Bolton’s ultra-religious minion, setting the agenda and making pronouncements, while we’re distracted by Donald Trump’s tweets.

Their choice to “return democracy to Venezuela” is Elliott Abrams, an interventionist expert in dirty wars, convicted in 1991 for lying to Congress in the Iran-Contra scandal. He was one of the creators of the Nicaraguan contras, and a war that cost thousands of lives. His curriculum includes El Salvador. He described as “communist propaganda” the December 1981 El Mozote massacre, in which the Atlacatl battalion, trained and armed by the United Staates, killed nearly 500 Salvadorans, including children and women. He was also the architect of the the most despicable Central American war. in Guatemala, with its more than45,000 disappeared.

Like Bolton, Abrams has no problems with managing his past. No regrets or doubts. Indecency should be incompatible with a democracy. It is true that in every state there are sewers, and one hand doesn’t know what the other is doing. But it is never presumed or a second chance offered to the amoral. For them, dissimulation is essential, a certain theater of decency, so that we can continue thinking that we are the good guys in the story.

Venezuela… and the US and Canada… and Mexico (eventually)?

I’ll be back to talk about things here, and I worry that what is being blatantly done to Venezuela, will be done (more subtly) to Mexico… but for how…

Back next week…

Household moving weekend…