Evelyn Trent (1892- 1970)

Jesse Olsavsky, in Jacobin, writes of one of those too often overlooked Mexico City gringa “influencers” who… whatever she was up to here, had a major impact on India’s own anti-colonial struggle.

Trent … received her first experience of revolution in Mexico City rather than Moscow. Mexico, whose revolution began in 1910 — initiating the epoch of socialist and anti-colonial revolutions — was then in a ferment. Emiliano Zapata had yet to be assassinated, and Pancho Villa had recently launched a small-scale invasion of the United States.

While the Mexican Revolution would take its own path… borrowing something from Communism, but emerging as something very different (and for many years turning towards neo-liberalism) Trent — who Olsavsky claims was the one who “converted” her husband, the Indian nationalist exile M.N. Roy to Marxism, she was active, both writing for the then radical El Heraldo and a serialized book, Mexico and Her People… perhaps limited by what she gathered from the Roy’s elegant home in Roma Norte), but nonetheless:

A deeply anti-patriarchal and anti-imperialist portrait of Mexico, with some forays into class analysis as well, this long-forgotten book stands out as one of the first of many romanticized accounts written by foreign communists such as Vladimir Mayakovsky and Sergei Eisenstein about the country that had experienced a major revolution many years before Russia.

During her stay in Mexico, she was also active in the feminist wing of the Mexican Socialist Party, organized a “Friends of India” committee, and at one point hid out the globe-trotting (on a forged Mexican passport) Mikhail Borodin.

And has been largely forgotten. She doesn’t even have a “wikipedia” entry.

A city upon a hill

Photos by Quoc Nguyen.

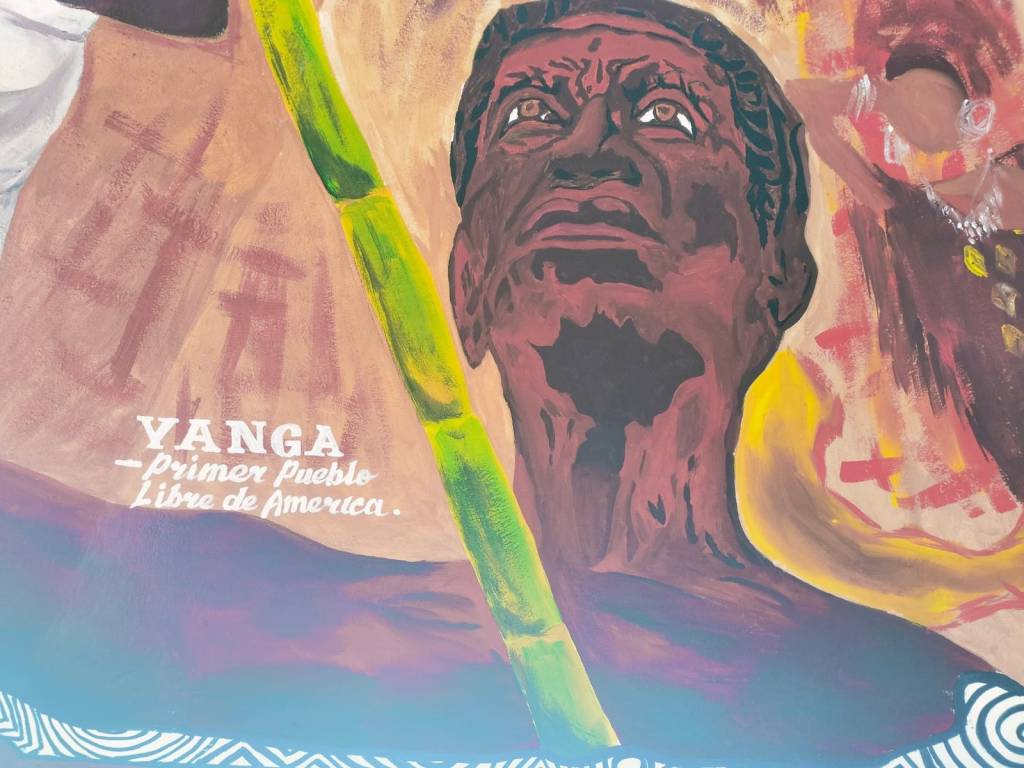

Two years BEFORE the Pilgrams landed at Plymouth Rock, the municipio of San Lorenzo de los Negros was granted a charter by the Spanish crown. Other than pointing out that colonialism and “civilization” were in the Americas long before the English bumbled on the scene, why is the founding of a small community outside Cordoba Veracruz so noteworthy?

The small city changed its name to Yanga back in the 1930s in honor of its founding father: an escaped slave who had organized a slave revolt back in the 1570s, establishing a refuge inthe hills over Cordoba and welcoming an influx of other escaped slaves. In 1609 (yes, that’s 9 years before 1618), and for a few years after, the Spanish sporadically attempted to capture the settlement, every attempt at re-enslaving the inhabitants, or destroying the refuge, failing.

In the interim, despite the occasional raid by the Spanish, the community was self-sufficient and a relatively prosperous rural town. One with slightly different customs than other Mexican communities perhaps, but ones lasting down to the present. Better to negotiate… “leave us alone, and we’ll leave you alone” compromise worked out, which — the new municipality NOT being an indigenous community that was expected to submit to the crown, besides being exempt from the usual tribute — making the small bit of free Africa the oldest community of its type in North America.

Slackers and Influencers

(I must have been seeing double by the time I posted last night (this morning)… an entire paragraph out of place, since moved)

The last few days, I was on a futile hunt for Bob Brown’s “You Gotta Live” published in 19321 … a “roman a clef” on the life and adventures of a wannabe 1920s “influencer” here in Mexico City,. While Brown and others in that post-revolutionary “milleu generally came to Mexico for political reasons, the 1920s and 30s “slackers” and “revolutionaries” wouldn’t have been all that out of place moving among the “digital nomads” and “influencers” of Condesa – and might have lived in the same building – were they to magically return to life.

I’d vaguely heard of Brown before… one of the “slackers” who first showed up mostly evading the US or British draft during the First World War.

The Revolution had not really ended by that point, but there hadn’t been fighting in the Capital since 19152 and the city itself was considered “safe”, the concerns in the popular English speaking media bout “rampant revolutionary violence” in Mexico standing in for today’s worries about “narcos” everywhere EXCEPT the capital. And, anyway, the then new Condesa development was where you found the “right” kind of Mexican.

While there were a few, like Arthur Craven, who — based on having been a postumous nephew of Oscar Wilde (his mother was the sister of Wilde’s wife, Constance Lloyd) — had set out on a career of making himself, if not a celebrity in the contemporary sense, at least famous among the “bohemians”. He tried his hand at a few things… as an “intellectual” boxer (fighting a match in Spain against Jack Johnson, who would later turn up in Mexico City himself, avoiding US legal authorites for the “crime” of having a white wife (who was also underage in some states) and extradition treaties. Then, feeling the ill-winds of the British draft, the marginally known “Dadist poet”, Craven, came to Mexico City where, he presumed, a revolutionary state would welcome with open arms a “revolutionary” poet. Craven DID become famous, but not perhaps in the way he intended.

Finding himself with a pregant girl-friend (the English poet, Myna Loy) and the Mexicans with better things to worry about than the well-being of English Dadist poets, as well as a general indifference among the “expats” to any but their own promotions and projects, set out on a ill-planned scheme to move to Argentina. Setting off from Salina Cruz in a leaky boat, he was never seen again. But, like Elvis Presley or John Kennedy, Jr. was said to occasionally be sighted in various locations around the globe for years after.

Of course, there are Cravens today… except now they push their “unique” or “cutting edge” productions on Instagram or Tic-Toc, or advertise their wares… for foreigners in the city (meaning Condesa and the surrounding area). Dadism is out, but there surely is a demand (within the foreign “community”) for “revolutionary diet plans” or a new musical style or… whatever. There’s nothing wrong in themselves with pushing some new concepts and ideas, but one hopes that finding the expat market rather limited, there’s some better backup plan than building a boat and sailing to Argetina. At least enough money for a return plane ticket.

A century ago, Mexico was emerging from a convulsive revolution and with political change came intellectual ferment. Certainly Mexican intellectuals — both holdovers from the old regime, and the up and coming young poets and artists and writers were active. But, for the most part, ignored as much by the “expats” (a term that didn’t enter the vocabulary until much later) as Craven was. While there was another “revolutionary” capital undergoing a cultural revolution too (Moscow), it was too cold, too far from the United States, and to learn the language, you had to decypher a whole different alphabet. And the political committment was much more flexible than in the Soviet Union.

Those expat pioneers (although the word “expat” wouldn’t come into use until the 1950s or so) were more likely to be impelled by political reasons — generally leftist — to decamp to Mexico.

It is all too easy to idealize a social upheaval which takes place in some other country than one’s own

Edmund Wilson, “To the Finland Station”

The “Great War” was obviously one factor, Mexico being a neutral country, not on good terms with any of the allied (English speaking) countries, but not openly hostile either. Bob Brown and Arthur Craven were hardly the only ones, at least one hotel becoming known to the Engish speakers as “Hotel Slacker”… “slacker” the derisive term of the time for draft evaders. But when I come to think about it — having made a career of iterenent employment as a contract writer, in between bouts of “whatever paid the bills” and bumming round for years … and being vaguely lefty … I guess the more modern use of “slacker” might apply to me as well.

So, I can’t sneer at that earlier generation of foreigners who take up residence here to stay. Not entirely, although when I read about them (my source right now being Mauricio Tenorio-Trillo’s “I Speak of the City: Mexico City at the turn of the twentieth century” [University of Chicago, 2010]) i’m bemused and amused that even with the best motives and willingness to learn and observe, we can get things not quite right.

While there were those later emigres like Victor Serge and Leon Trosky who had already been influential in Mexican political thinking, there was also M.N. Roy. An Indian nationalist, Roy had seen armed resistance to the best path to liberate his country from British colonial oppression. With the Germans, as part of their policy during the “Great War” being to limit the number of troops Britian could field in Europe by creating problems elsewhere in the Empire, naturally — “the enemy of my enemy…” — was a likely source. The British caught on, and Roy had fled to the United States, taking up with a California heiress, Eleanor Trent. As a “colored” man with a white wife, he’d been forced to flee tthe United States, setting up a rather swanky establishement in Condesa-adjacent Roma. Although a dedicated Communist, Roy and Trent lived well, with servants and, outside of a few intellectuals like himself and his friend Deigo Rivera (another high-living leftist) founded the Mexican Communist Party. Roy and Trent later split, Trent remaining for many years in Mexico simply living (and, a shame she never wrote her memoirs), while Roy and his second wife went first to the Soviet Union, then back to India, where he was one of the founders of India’s still relevant Communist Party before turning to the incomprehensible (to me, anyway) “Radical Humanism”.

While Roy was probably the best known, there were plenty of other foreigners who, were less looking to change the world (or at least Mexico), from their vantage point of the “gringo ghetto” of Condesa 3 … and are very much in the spirit of today’s “podcasters” and “influencers”. I know, hard to believe, but there was a time when the internet didn’t exist, and to get “your truth” out there, you had to publish in a magazine. Those who stayed into the 1930s or 40s (or made their lives here, like Anita Brenner (technically a Mexican, since she was born in Aguascalientes but taken to the US as a baby) turned to writing tourist guide books, or otherwise simply marketing the Mexican stereotypes… “Sunny Mexico”, full of exotic friendly “natives”, and a leisurely pace of life. And the excitement of “uncovering” little known interesting sites… you know, the same stuff put on on podcasts today. And, with, as then, excusions into the deepest, darkest corners of the (not Condesa) parts of the city. Occasionally, although then as now, there’s the warnings that Condesa-Roma are the “safe” areas, maybe Coyoacán and a few other places, but if you see a podcast on any other part of the city, it’s in the form of some derring-do safari into unknown territory.

Those 20s and 30s writers did the same, and perhaps worse, created (naively or unintentionally one hopes) stereotypes that linger to this day. Tenorio-Trillo gives several examples up through the 1940s of what he calls modern “casta” paintings… showcasing Mexican racial “types” although as he points out, that “pure Indian” may not be so pure but looked to the photographer like an “Indian” should look. Or presented those wearing more traditional clothing styles (which traditon’s style?) as “authentic” as opposed to Mexicans wearing more what’s available at the department store as “modern” Mexicans.

If, that is, the Mexico our “foreign community” seeks is “México profundo” and not– ironically perhaps — the Mexico our “white lens”4 brings into focus. Not to belabor the point, but Oscar Lewis (“Children of Sanchez”, etc.) who ventured out from Condesa, and explored those hinterlands of the city more than any other gringo, never went in Mexican drag.

As to the final poinr: then as now, you had the “expats” who flaunted”natifve dress” to signal some sort of idenification with the people. While yes, of couse, some people just like the clothes, or find some particular item fits their needs. but then, as now, it’s ofen seen as seriously as it is to see any adult playing dress-up.. Even Frida Kahlo was understood by her peers to be in “costume”, and her style (appropriated from the Zapotecas) was more a way of self-promotion. What seems different with the 21st century “influencers” is that whereas a century ago, the rationale was to be “one with the people”, it seems today to be to market either one’s self, or one’s product, to the other foreigners as “more Mexican”.

I don’t see that either the leftists of the post-Revolution or the “digital nomads” and “influencers” of today really mean to impose “gringolandia” on Mexico, but view the country and its cultures (not culture) through a “white lens”4 Even the hardest mercenary minded AirBnB gentrifying realtor doesn’t want to turn the country into USA-lite. Not consciously, anyway. Instead, what seems to happen, then, as now, that in order to make a living, or at least to justify one’s continued existence in the country, our options are limited to selling whatever skill set we bring here, which aren’t all that useful, or things that can’t be met by the local market or expanding the market for “Mexico” to other gringos — bringing in yet more gringos to “share the experience” which, while bringing in the tourist dollars, is based on successfully selling not Mexico as it is, but the Mexico of our expectations.

Even those who are only here because the rents are lower here than wherever it was they came from (and consquently drive up the rents in their favored haunts) will claim contributing something to Mexico… if only some sales taxes, or, more selfishly, to claim it broadens their experience, and makes them better citizens of the world. Otherwise, its pretty much teaching English, working for a US based business whose management can’t (or won’t) adjust to other cultural expectations and language, or selling gringos on the coutnry. in the past turning out magazine articles and travel books, today making podcasts (or writing a blog). Having done a bit of all three over the last 20+ years, it’s understandable, but if we are “teachable” we can, at least, not fall into trying to re-invent the stereorypes of the past (so many podcasts just cover the same sites, and often with exactly the same language, as travel writers were using back in the 1930s), or expect Mexico to follow “our” expectations, or focus on what “our” media tells us what Mexico is or isn’t (migrants and narcos are part of the story, but only part), try to impart what know, not be surprised when we don’t or that our assumptions are wrong, and hope we get most things right.

.

1 Brown died in 1970, and his British copyright (Hammsonworth, London, 1932) runs until 2040. The isn’t any PDF or Kindle version available, it’s not in the UNAM library catalog and the neasrest one I can find is at the University of Houston. I suppose some piratacal minded scholar could check it out, copy the 300 or so pages and send it down my way, but I would never suggest such a thing.

2 Rosa King, from an earier generation of foreigners in Mexico… a Curenavaca hotelier who had come to Mexico in 1907… wrote a eye-witness account of the fighting in the city (or it’s aftermath) in her 1935 “Tempest Over Mexico”. It IS available as a PDF and/or Kindle.

3 I lived not in Condesa, but in Condesa-adjecent Roma Sur for a three years. Not swanky by any means (carved out on the rooftop from a maid’s quarter) and only a cleaning woman that the landlandy dumped on me.

4 A term coined by the Mexican-american artist, Joaquin Ramón Herrera, to suggest the biases of one’s cuture imposed on our view of another culture.

Popo poops…

Are we the baddies, too? “Settler Colonialism”

As a US Supreme Court justice once said about pornography, “We know it when we see it”, the definitions of what exactly a “Settler State” is are nebulous and open to wide interpretation.

Oxford Bibliographies defines Settler colonialism as “an ongoing system of power that perpetuates the genocide and repression of indigenous peoples and cultures”. But what is “ongoing”?

The author, Alicia Cox, expands her definition to limit the term somewhat: “settler colonizers are Eurocentric and assume that European values with respect to ethnic, and therefore moral, superiority are inevitable and natural. However, these intersecting dimensions of settler colonialism coalesce around the dispossession of indigenous peoples’ lands, resources, and cultures.

However, as the Decolonial Atlas points out, and Lachan MacNamee argues in an essay for Aeon, “Settler Colonialism is not distinctly western or European“, taking, for example, the Japanese colonial occupation of Manchuria, and the Indonesian attempts to take West Papua. And, one might add, “disposesion of indigenous people’s lands, resources, and cultures” have been SOP in one form or another going back at least to Alexander imposing Greek/Maceconian regimes thoughout central Asia and the “near east” (near to whom, east of what? Our definitions — relatively near, but east of Macadonia, showing just how much European assumptions affect our world view).

Cox also limits her definition further, or rather attempts to do so, when she distinguishes between “colonial” and “post-colonial” studies:

… postcolonial studies and critiques the post- in “postcolonial” as inappropriate for understanding ongoing systems of domination in such places as the United States, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand, where colonialism is not a thing of the past because the settlers have come to stay, displacing the indigenous peoples and perpetuating systems that continue to erase native lives, cultures, and histories.

So are countries like Mexico… part of the larger post-colonial “global south”, but with a strong overlay of “Eurocentric” settler colonial states?

Maybe there is some sort of “statue of limitations” on colonization. When the Castillians showed up in 1521, they were themselves the heirs to earlier waves of colonizers … Catheginians, Greeks, Romans, Moors, Goths. And the same could be said about the other North American colonizers… the English, Dutch, French.

Intent and effect

In everyday use, we limit Settler Colonialism to relatively recent (from the late 18th century to now) colonialism — “post colonial” as Cox would have it — leaving the messy past to its own devices. By this metric, the Spanish Conquest wouldn’t count: It was a late medieval expansion of European (West European) territorial and resource control. That is, settlement — finding territory for people from the old country to live on — was less important for Spain than access to, and exploitation of, Mexican (and other colonial) resources. And at the same time, Spain was “interally colonizing” the Peninsula — or attempting to impose “European values” assumed to be morally and ethically superior”, to borrow from Alicia Cox. She might further see the forced assimilation and expulsion of the Jews and Moors as a crude attempt to “repress […] indigenous peoples and cultures (although Both Jewish and Moorish cultures were the earlier migration, and when you come down to it, Spain (or Castille) were very late when it came to expelling religious minorities… the last in a series of Jewish expulsions from Western Europe, beginning with England in 1290).

The “ethno-state” was not really a thing in the late medieval world. A “country” wasn’t so much defined by culture or language so much as by where you lived, and who ruled. Even without its New World possessions, “Spain” was a collection of peoples with different cultures and languages (and still is, to some extent) not to mention various spots thoughout Europe, in southern Italy and even Flanders. The Americas were just another chunk of territory, with a different population than Europeans were used to. That they engaged in massacres, rapes, pillages, and the other not-so-niceties of conquest of the time isn’t questioned. What is questionable is whether they were fully invested in impsoing those “European values”.

In a way, yes.

But, not by clearing out the native population.. as the British colonists in North America and Australia were keen to do, and supplant them with their own people, but with the “time honored” techniques used by conquerors forever… my way or the highway (bye!!!!).

Religion provides the most obvious example , and one with which the Europeans had had experience. Converting the Scandivanians, the Slavs, and earlier the Germans was more a matter of “convincing” (even if at the point of a sword) to convert, with the with the assumption that most of their dependents and subjects will go along. And, maybe just leaving a small remainder of people that need more forceable “persuasion”. Also, remember that during the Age of Exploration… that late medieval-early modern period, … it wasn’t only the Americas that saw attempts at mass conversion. The Jesuits, espcially, were active in China and Japan seeking to win over the elites. That the Church (was open to incorporating … or subverting… local customs and practices in a “Catholic “Christian” package — in Mexico leaving the “Gods under altars” — the identication of various saints with the earlier gods or deified forces of natuire — was no different that the incorporation of some mythic Roman or Irish or Scandinavian folk beliefs and customs with a “Christian” overlay (something even encouraged in the Catholic Church up until the Council of Trent).

Even by the 17th century, it was widely noted that there was a separate Mexican culture, not Spanish, not imitation Spanish, but one in which the native cultures (even in religious observation) adapted European technology and practices for the most part, although subverting them to their own ends. Is the Virgin of Guadalupe a native godess, the mother of Jesus, or something of both?

Other europeanizing features — agricutural patterns, technolgies, popular culture — might be labeled “cultural appropriation” by the colonized. Not to say it was always by choice, or that the intent wasn’t to force indigenous people to adopt “the right way” of doing things, or conforming to the expectations of the colonizers (as in a demand that “Indians” wear shirts and pants… or on the missions, to enforce attendance at Sunday Mass).

I’d argue that outside of a few regions in “Las Americas” (not English North America) there really wasn’t “settler colonialism” for the simple reason the Europeans for the most part never intended to settle in any systemic fashion. As colonialist, the Spanish were still of a medieval mindset.. not necessarily looking for settlement so much as exploiting those resources for the “metropol”. What “settlers” there were overwhelming those neecded to exploit and return to the metropol those resoures… crown officials, managers, skilled workers in those trades that served European interest.

Overwhelmingly men. Even though we sometimes assume the Conquistadores raped every woman they could (and no doubt the did), mesiaje was more just the by-product of a shortage of European woman, and while we sometimes forget it (or want to forget it), women’s lives sucked if they couldn’t get a husband back then. Women had the agency to improve their unenviable lot by “marrying up”, and naturally took, advantage of it. Or, with a dearth of indigenous men, thanks to wars and diseases, often had to take what they could get… as did the Europeans. Who, at least in the Spanish and Portuguese colonial empires, were even encouraged to do so, or at least, faced less stigma than English settlers who married “Indians”.

Post Colonial? Neo-Colonial?

Spanish America is free,and if we do not mismanage our affairs she is English.

British Prime Minister George Canning, 1825

Post-independence, perhaps we can begin to talk about a “post-colonial” society… one is which while the “yoke” of foreign cultural and political control was thown off, it was still strugging with the contradictions between the imposed culture (which had been around for 300 years) and traditions. Obviously, over those 300 years of colonialism, culture had changed (both in the “mother country” and in the “colonies” and there was no going back.

However, the British, and later the US Empires were at their height and quick to scoop in. Canning was very much in the “old” imperialist mode, less concerned about imposing his culture than in taking over the exploitation of now ex-colonial resources. Humbolt (in his 1803 “Political Essay on New Spain”) and Henry George Ward’s “Mexico in 1827” didn’t so much set off a British (and to a lesser extent, French) land rush as it made Mexico a target for speculative investments. And, a likely target for exports.

Being good Liberals, the English were willing to do business with the “dusky hordes” … with a proviso. Liberalism merely implied all money and business is equal, not “all men are equal”. Of course, the post colonial ruling class, while more ethnically mixed, were those who’d been elites, but not the political ruling class, under the old regime. In other words, already “Hispanicized” in their manners and cusoms. Although non-Europeans were absorbed into the new leadership, it was with the assumption that they confomed to the mores adopted over the long colonial period. These included a deference to European (and presumably “better”) thinking especially when it came to more theoretical questions about politics and economics.

That deference to foreigners is something of a cliché, but one that appears to be a feature of post colonialism… trying to adapt whatever the outside power (which became the United States, especially after the US invasion, occupation, partial annexation of 1846-48) as close as possible to the original, “their” way.

You can see this in immigration. Even by independence, the percentage of Europeans was a small fraction of thw whole (2% European born, 10% total of all what today we call “white”, the majority of mixed indigenous and European, African and Asian descent, with a quarter still considered indigeous, according to Alexander von Humboldt and extant census data there was).

The suggestion from the census data would suggest that wiping out the indigenous populatin was never intended… and I have argued that it wasn’t, with no “conscious genocides” (with a few exceptions) having ever been sanctioned. The “American holocaust of the 16th century (with the population dropping anywhere from 50 to 90%) had more to do with the accidental (an uninteded) introduction of “old world” diseases than anything else. It wasn’t until the English began their sporadic “smallpox blanket” campaigns in the 18th century that we hear of intentional biological warfare.

As an aside, I might point out that one example of “settler colonialism” I read often in US discussions is the California missions… which one can’t argue were not concentration camps for indigenous people. And, whatever good intentions the missions might have had, as we know, the road to hell… and the California holocause was in the 1850s and into the 1880s, after US annexation.

But… as the English, USA, and other Europeans developed a “racial science”, Mexico, and other Latin American nations, were desperate to “whiten” their populations. If not to become European, than at least to become “less Indigenous”. Today, even those who claim “Spanish” ancestry trace their families arrival in Mexico or elsewhere in Latin America only to the 19th or 20th century. That even these “new” Mexicans were mostly men, and married “native” women (whether of complete, or mixed indigenous, or African, or Asian, or all of the above, background) may havwe fulfilled the scientific racists of the 19th century’s goal of “whitening” the population somewhat, but the “Cosmic Race” (as José Vasconcelos dubbed it in his own race-obsessed work) has never been seen in the context of a autochthonous culture, as Russians, Chinese, Scandinavians … who’ve certainly changed over time… are.

Are we (in Mexico) the baddied, or is it the “great power” to the north? “Post-colonial”, given the onslaught of cultural dominance by, or, maybe “neo-colonial” given it’s economic dependence on, and constraint on its foreign affairs by, the whims of the “great power” to the north.

As the judge said, “we know it when we see it.”

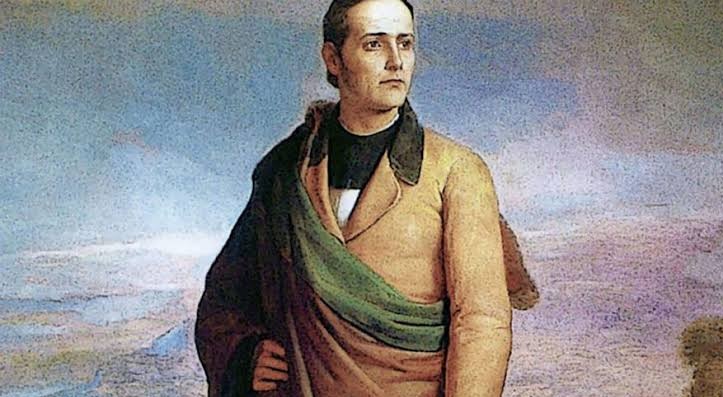

Mariano Matamoros (14 Aug 1770 – 3 Feb 1814)

While not the best known name on the short list of Mexican military leaders, Matamoros certainly was remembered … if only vaguely … in a number of geographical names scattered around the map: Matamoros, Tamaulipas; Izucar de Matamors, Mexico; Matamoros, Coahuila; etc.

His fame rests mostly of having defended Cuatla (now Cuatla de Matamoros,) from Royalist forces during the war of independence, breaking though the seige, only to be captured and summarily shot..

… which, the Royalists weren’t supposed to do. You see, Matamoros was not a military man, but a priest, entitled to a clerical trial. A product of the creole middle class, Mariano was born and raised in Mexico City. Like Hidalgo and Morelos, his pastoral duties as a country priest with a higher education, radicalized him, making him an early adherant of the call for independence.

The early independence revolt went horribly wrong, with the original conspirators — Hidalgo, Allende, Aldama and Mariano’s heads ending up hanging from the Alhóndiga of Guanajuato’s walls with a very short time. Leaving Morelos, the cowboy turned priest turned general, to lead the war. Matamoros, city boy that he was, as a priest perhaps, became particularly close to Morelos, giving command of his own units and becoming — as an artillery officer — not an expert on canon law, but on cannon law. He led the break out from the 72 day seige of Cuatla, the army’s escape covered by the 12 year old cannoner Narcisso Menoza, on 12 May 1812.

Promoted to General, Matamoros continued harrassing and wearing down Royalist forces for the next 21 months, until captured at the Balle of Puruarán (Michoacán) in January, and … ignoring his rights as a cleric to a religious trial, put up before a firing squad and shot… leaving him, as all great Latin American heros are… young, handsome, and dead. Or, at least with a couple town named for him.

The Demon and the Nun

To his enemies, Felipe Carrillo Puerto was the “Red Demon”. To her admirers (and enemies), his sister Elvia was the “Red Nun”. Between the two of them, they brought more change to the Yucatan in two years than there had been in two centuries.

The Yucatan of the late 19th century was, in many ways (and still is), an outlier in Mexico. Its economy at the time rested mostly on sisil (used for making rope) exports, and tied economically more to Cuba and the British Caribbean than to Mexico as a whole. It had, as had Texas (and at the same time) been a seperatist republic, only brought back into Mexico when the ruling elite sisil plantation owners (the “divine caste” as they styled themselves) were nearly driven out by what essentially was a proletarian (and serfs… yes — serfs) revolt known as the Casta War. While — technically — slavery did not exist, the conditions of the Mayan majority was a little below that of African-Americans in the post-Reconstruction US South, the worst of the “Jim Crow” era. Mayans could not vote, hold office, or even walk on the sidewalk when a criollo went by, no matter what the laws might say. The “Divine Caste” liked it that way, and preferred to spend their ill-got gains on elegant homes in Merida, or on their plantations to anything that might ease the lot of their “peons”…. roads, housing, and the like, let alone basic human rights.

The extremely large Carillo Puerto family (there were 14 siblings) with a Mayan father and criollo mother. Desite — or because of — the discrimination the children were likely to face, the bilingual and bicultural Carriollo Puertos were conscious of their needs to come across as “the good ones”. Half the despised minority, they had to be twice as good at whaterver they did… and for Elvia, being a woman… four times better.

Obtaining any sort of career would be a challenge: Felipe (born in 1874) went to work for the railroad (what few rail lines there were in Yucatan meant he traveled throughout the Republic) while Eliva (born in 1881) managed to obtain a secondary school education, despite being married off at 13. Widowed at 21, she opened a primary school for Mayan girls.

Both were inveterate readers, intimately familiar with their father’s culture, and able to express themselves in their mother’s tongue. Leading both to journalism, and to political agitation for change. They were hardly the only ones, with Felipe slowly building a political career, moving further and further to the left. Elvia — based partially on her own experience having become the mother of four by the time she was 21 — naturally focused not just on women’s sufferage, but the then radical cause of birth control (and, incidentally, was one of the few proponents not also pushing the now discredited eugentic movement).Being a somewhat forgotten corner of Mexico, the Revolution came largely from the outside. Salvador Alvarado, a Sinolan druggist turned general came marching in with the Constitutionalists in 1915, ready to take names and kick ass.

There’s no denying that Alvarado made massive changes, although… again like the post-Reconstuction Southern United States… they were well intentioned, and had the potential to radically reform the region (things like opening agriculural colleges, not standing in the way to protect plantation owners whose peons seized the land, and abolising the petty discrimination laws it did little to change the entrenched attitudfes and prejudices that had festered over the last few centuries.

However, it did open the doors to politicians like Felipe and Elvia. Even if women couldn’t vote, nothing said they couldn’t run for office, or hold it. Since 1912, she’d headed the “Feminist Resistance League”, building a cadre of educated middle class and working women pushing for yet more change. She would be the first woman in Mexican history elected to a state legislature. While she wasn’t seated, the popularity of women for the Revolution was enough to give women the vote in state elections.. a first in Mexico, and one that Felipe — having become head of the Southeast Socialst Party (which he founded) would push though when he was elected governor in 1922.

As Governor, he pushed through more Mayan education (Alvado’s schools only had Spanish, effectively limiting Mayan advancement to a very small number of citizens) and… at the behest of his sister, Yucatan became the first place in the Americas to not just legalize birth control, but make it freely available. With his railroading background, he was a century ahead of his time, realizing the need for a diversifed economy less dependent on a single crop and foreign exports. And. he reconginized one economic sector not much considered at the time: tourism.

Not only would tourism diversify the state’s economy and create jobs (even if crappy ones, an alternative to cutting sisil), but also create an awareness of, and appreciation for, Mayan civilizations and cultures. And a need for not just tour guides and waiters, but well-educated Mayanists. One of his unfinished and most ambious projects was not just the archeological exploration of Chichin Itza, but his plans to build trains to carry those tourists, and to bring transportation to the rural masses and whatever industrial or manufacturing opportunities might arise.. something finally being done now.

With Elvia as his back, he also consciously appointing women and Mayans to executive positions with the state government (an early form of affirmative action). He was pushing for yet more, and more radical change, when the fall-out from Carranza’s attempted self-coup led to uprising throughout the country when Alvaro Obregon sought to “consolidate” the Revolution, and conservatives, radicals, and the “centerists” (like Obregon, the evenual winner) took up arms. The Carillo Puertos were clearly on the side of more change, a workers state, but alas…

Only two years into his revolution from above, he … and eight of his siblings… faced a firing squad for supposed “treason” on the third of January 1924. Elvia survived (she fled to Mexico City) continuing her work until she was blinded in an auto accident in the 1950s. She died in 1968, having won her long struggle to bring women into government and making Mexico one of the world leaders in birth control What she would think of the upcoming election in which two women are the leading candidates, one can only speculate.“The murder of Felipe Carrillo Puerto brings sorrow to the homes of the proletariat and to many thousands of humble beings who, upon receiving the news, will feel tears of sincere pain slide down their cheeks. Don Adolfo de la Huerta will understand the monstrosity of his crime when he receives the furious protests that workers from all over the world will launch.

Alvaro Obregon Mexican revolutionary, President of Mexico (1920-1924)

Saving souls… and axolotls

I never saw an axolotl

But Harvard has one in a bottle.

(Ogden Nash)

I have met the iconic Mexican salamander … live, and in my pocket (there’s an axolotl on the 50 peso banknote)… and — as in the BBC broadcast from about five years ago — you can get them in a bottle.

“

Mexico another + in BRICS+

Maybe, maybe not: https://mexfiles.substack.com/p/brics-eesiu-m

What’s wrong with this photo?

Born in Guadalajara in 1917, and never quire finishing high school, and tooling around with junk parts from his radio gig, this guy completely changed the way we see the world.

Despite not having any degree, Guillermo Gonzáles Camarena was a proficient enough radio engineer while still a teenager to be hired by the Mexican Department of Education radio department. From junk parts he built a television set in 1934. Not the first person to do so, by any means, he recognized how crude, and flat the images were, and started thinking about how to improve those images on the screens… and by 1940 had patented his new invention, although there was an experimental broadcast of improvements he’d made in his original patent in 1949 (live … from an operating room in Hospital Juarez) it was only in 1963 that manufacturers began releasing to consumers televisions with the features he’d been continously upgrading for 20 years… color television.

So, why are all his photos black and white?

Riding that train…

Everything old is new again. Or, maybe being the last day of 2023, I should say, “Ring out the new, ring in the old”. This year, and in 2024, it’s not new highways that the politicans promise, but railroads… and they’re delivering.

As early as the 1830s, there were proposals to build rail service, although… between the instability of the government, a few wars, and … well… no investors, nothing happened. In the 1850s, following the US annexation of California, and the gold rush, led to US proposals (i.e. “demands”) for a more secure comunications beween the new Pacific region and the eastern seaboard. Yes, “Manifest Destiny” was pushing the country futher into the interior, but, it didn’t seem possible to build any reliable link between the two “settler state” regions. And those pesky Indians were not about to grant access. On top of which, the British hadn’t quite given up their hopes for warm water ports on the North American Pacific coast.

Panama was the shortest route, but at the time, it was impossible, and the most popular route, from the east sailing to Nicaragua, getting on Commodore Vanderbuilt’s railway to Lake Nicaragua, crossing the lake on Commodore Vanderbuilt’s steamships, staying in Commodore Vanderbuilt’s hotels, and taking another train (owned by, you know who) to the Pacific, to sail on ships also owned by the oligarch to California, had it’s “national security” problems.

Alll of which led to the “McLane-Ocampo Treaty of 1859. Although it was hardly the “dirty deal” that Mexican conservatives to this day claim would have given the United States control of the Isthimus of Tehunatepec, which seems to have been in the mind of those Manifesting gringos, it was one of those not quite “free” free trade agreements. Besides all the goods exported and imported from or to California … for which the United States would have just paid Mexico a set fee per year, rather than deal with customs inspections, and duties, it would have allowed the transport of military forces and equipment, a real concern given the influx of not just “pioneers” and prospecters pouring into California, but all manner of rouges, grifters and political radicals.

HOWEVER, given that the American Civil War was a more pressing issue, the treaty was never ratified, and nothing was ever done. But a trans-ithumus railway project (or, alternatively, a canal… a theoretical project going back to Hernan Cortés) never went away. (more on that here)

Although a short line was built during the Maximilian’s short reign (more as bragging rights for the Austrian, to claim the country was being modernized than for any practical reason), by the 1870s, especially after the US Transcontinental Railroad was completed, there was something of a rail-rush in Mexico. Mainly because the US wanted to exploit Mexican resources, of course.

The trains were a good investment… usually. There was the usual fraud (this was the “Guilded Age” in the United States, after all), with dupes like even Ulyses S. Grant being taken in. Anthony Trollope’s 1875 “The Way We Live Now”… a satiric look at the English aristocracy desperate to maintain their status in a world wealth and privilige was shifting away from those with landed estates to those with financial resources… centers on a stock market fraud involving a bogus Mexican railroad investment. But those that were build were in the hands of US and British investors.

And… just co-incidentally… involved, as in the United States and Canada in the same era… removing the communities in their way, although in Mexico, these were usually settled agricultural communities, who found their lands given away to investors without their say-so. Something that would come back to haunt the rail-builders

Under ther dictatorship of Porfirio Diaz… who to his credit, or that of his economics team… at least realized that foreign ownership of a national transportation system was not in the national interest, began buying shares of the foreign owned railroads, by the end of his rule consoldating several into the state-run (or, rather, “private-public partnership”) Ferrocarriles Nacionales de México. Which proved to be a convenient tool for the forces that would overthrow his dictatorship, and in the civil war/revolution that resulted.

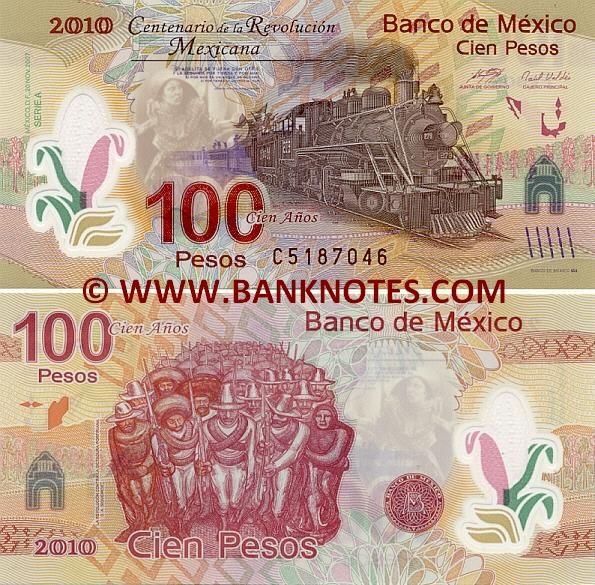

As it was, it might have been that those railroads, or railway workers, were key to the Revolution. With the trains running to the United States by design, the railway workers were instrumental in smuggling not just the anti-Porfirian propaganda from exiles in the US, but their leaders (like Franciso Madero who had to flee prison disguised as a brakeman) and, once the fighting broke out, run through the weapons and material needed to keep the revolutionaries in the field And serve as military transport. Most of the major battles between 1910 and 1916 were fights to gain control of the railyards. As commemorated in a 100 peso bill of a few years back:

The revolution did not overthrow EVERYTHING. The Mexican state continued to buy out railroads, and even managed to somehwat expand the service, notably the Copper Canyon Railroad, completed in 1961.

And, it’s hard to underestimate the railroads’ impact on the population. The Revolutionary road (so to speak) brought more than soldiers and weapons, but teachers, doctors, adminstrators to places along the routes, or reachable from rail stops. For better or worse, “development”. It’s probably impossible to say whether the north industrialized because of the railroads, or that the industries localed along the railroads because of the ease of export. Either way, with the reailroads running (and still running) mostly north …as wikipedia says

… freight and passenger service throughout the country (the majority of the service is freight-oriented), connecting major industrial centers with ports and with rail connections at the United States border.

… Mexico has become mostly a supplier to the United States.

While likely to remain true for a very long time (though, Mexfiles would favor more trade with other parts of the world and a more balanced export/import scheme), the United States and the ways of the United States have dominated Mexican development plans since at least the late 1940s. This isncles, favoring automobile and truck traffic over rail. And… given the “neo-liberal” mindset of the 1980s until recently, “privatizing” public services.

Passenger service has been phased out (with the exception of a few tourist lines, and urban lines, there hasn’t been regular passenger service since the 1990s) and Ferrocarriles Nacionales was killed by the Zedillo administration, when the several lines were given as “concessions” to the major US railroads (with one exception, for a southern line controlled by a Mexican corporation).

Neither of which turned out to be the best way forward. Or, given planetary concerns like a need to lower fossil fuel emissions, not to mention loss of agricultral and forest land to roadways, it turns out old-school 19th century solutions are better suited for 21st century problems.

Within the past year, we’ve seen TWO major rail projects at least at the test stage… an interurban line between Mexico City and Toluca, the new Mayan Train (mostly still for tourists, but bringing “devlopment” to a long neglected, and railroad-less region), and as of earlier this week, a rebirth of the Trans-Ocieanic corridor. Add to that that those privatized freight tines running to the United States now MUST add passenger service on their lines, under a reborn Ferricarriles de México… and one might say we’re on the right track.

… as to the Mayan Train (and first long-distance) public rail development project, these kids did a great job, although a few of their remarks, made in an attempt to present “both sides” of an issue, might need a corrective, kindly provided by commentator “violamateo”.

@violamateo

I’d like to point out just a few things, some of which you’ve touched upon and other which you haven’t:

1) a LARGE part of the opposition to the Tren Maya has come from right-wingers who are itching to get back in power, so anything that López Obrador does (especially in terms of social benefits or infrastructure) is viciously attacked by them.

2) Curiously, nobody’s ever said a word about all the ecological destruction that was done (and continues to be done) in Cancún, Tulum, and Playa del Carmen, due to so much hotel and road construction, water extraction, etc. But now with the Tren Maya, everybody’s an ecologist! It’s important to mention that experts in engineering and archeology were constantly being consulted during the train’s construction.

3) You briefly mentioned the jaguar, and it’s a legitimate concern. But what you failed to mention (even though I imagine you saw some of them) were the so-called “pasos de fauna”, ginormous overhead bridges (totally planted with vegetation) by which the jaguars and other local animals are able to freely cross the train tracks without having any direct contact. They’re not roads, but are ONLY designed for animals to cross. Additionally, they include elevated wire structures so that monkeys can also cross, and there are even provisions being made for bats and other species. There are 547 of these bridges along the entire route, which is more animal crossings than have ever been built in the entire country’s history!

4) The fact that this region has traditionally been one of the country’s poorest means that the Tren Maya is going to bring a big economic boost to the area, not only providing jobs for the locals, but by promoting archeological sites and expanding the hospitality industry as well.

5) Finally, the fact that not every train is going to be jam packed with passengers doesn’t necessarily have to be a negative thing either: The train is scheduled to also carry a great deal of cargo. [… and,, I’d add, this video was only made the secord or third day of operations… give it time to catch on and the kinks to be worked out. Geeze!]

¡Feliz navidad!