Your Mexican visitor today

The genetically mutated Meleagris gallopavo on your dinner table was first served to Europeans in 1519, at Cozumel, where Mayans, like the Wampoags a century later, would take pity on some hungry foreigners and serve them up a decent meal featuring what was a staple of the north American diet. Pedro d’Álvarado would begin his career in stealing treasures from the natives with a couple of the birds, which he mistook for peacocks: a native bird of Iran, and known to Europeans through contact with the Ottomans… i.e. Turks.

While the peacock is mostly an ornamental bird, our bird is quite a bit tastier (and has more meat), and our humble American bird was dubbed by the Spanish, “pavo”: peacock. The showy (and not particularly useful) peacock was promoted to “pavo real”… or, now, “royal turkey”.

The English, being late to the imperialism in the Americas game, were already somewhat familiar with the bird a century later, by which time they’d mixed up the dethroned Ottoman peacock with the Spanish word for the American bird… and dubbed it “turkey”. By the 18th century, the English were breeding them prodigiously, and by the 20th century … the toms having been bred for larger and larger and larger breasts are unable to breed the natural way… and those frustrated adolescents on your table probably welcome their fate as a relief.

In the countryside, most homes will still have a few hens and maybe a tom wandering around the yard…in their original glory. Politicians don’t always give away frozen ones at election time, but the live birds, though it’s technically illegal now for the pols to tell you the turkey is in exchange for your vote in the next election.

Here, while you see “pavo” on the labels in the supermarket, we remember it’s “our” bird, and call it by its nahuatl name, “guajolote”.

Gone, baby, gone

“From 2009 to 2014, 1 million Mexicans and their families (including U.S.-born children) left the U.S. for Mexico, according to data from the 2014 Mexican National Survey of Demographic Dynamics (ENADID). U.S. census data for the same period show an estimated 870,000 Mexican nationals left Mexico to come to the U.S., a smaller number than the flow of families from the U.S. to Mexico.”

(via National Council on La Raza, commenting on this story)

I’ve been hearing as long as I’ve lived here the unsubstantiated figure of a million USAnians living in Mexico, which may even be true by now, but by no means are there a million “expats”… which seems to mean retirees in the gringo ghettos around Chapala, San Miguel, and along the coats, a sizable number of quasi-illegals (the “border runners” who try to have it both ways — living here on the cheap, but who don’t qualify for residency, and claim to be tourists, making regular trips out of the country) and the relatively large number of those who (as I was for a while), being white people with some money coming in from the outside, don’t like to be called “illegal immigrants”.

Of course, implying that the million gringo figure is people like “us” is self-serving. When not dished up by real estate agents trying to convince someone that a house is not a house, but a financial instrument that can be sold at a profit to the supposedly limitless gringo community, it’s usually bandied about by those who complain about some minor “inconvenience” to them in the immigration procedures here — the people who somehow get the idea that spending money on rent, and housing, and maybe their underpaid “help” is a boon to the economy.

As opposed to those U.S. born (and U.S. citizen) dependents of Mexicans who have returned here, and who are likely to spend their lives here as taxpayers and will be contributing to the economy (and the culture) long after us geezers have cashed out last Social Security check, and bought our last eight-pack of Pacifico … and whined our last whine about being expected to give the kid who bagged the beer a whole three pesos.

…..

And, as long as I’m on a roll… the U.S. is losing a million families off the tax rolls, and it freaking out that 10,000 Syrians MIGHT be coming. Absurd.

I wonder what they talked about

Reproductive tourism?

That’s a new term for me. Notice the financial figures. The mother received 10,000 US$, but the price for surrogacy in Mexico runs about $50,000 US. What’s the overhead? Maybe the surrogate mothers need to unionize.

Operation Wetback

Dara Lind, writing for Vox, has done a bang-up job of going into the background of “Operation Wetback” … the overly hyped (by the overly-hyper Donald Trump) “round-up” of Mexican migrants in the U.S…. the largest mass deportation in U.S. history: maybe.

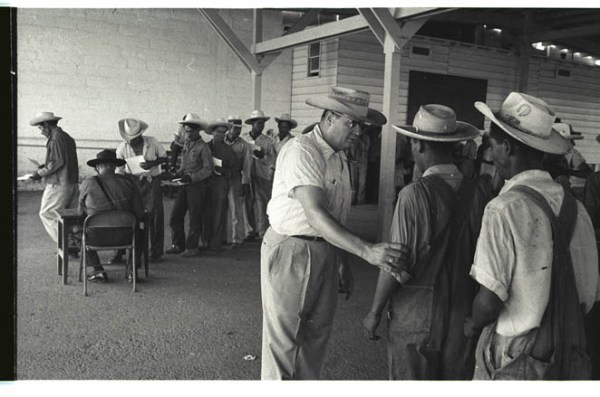

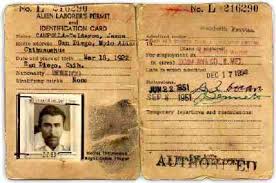

Inspection of Braceros – Braceros being inspected as they enter the United States, 1956

Rather than repeat what Lind says, I recommend reading her article, with the following additional bit of information that is often overlooked:

The Bracero Program was a war-time measure by Mexico to support the allies with manpower that would free up other men for military duty. Because of the war, and Mexican support for the allies, the country was rapidly expanding industrial production, and… after the way… state policy favored industrial development and expanded commercial agriculture. During the War itself, as in the United States, women who had never been considered part of the work-force were hired in huge numbers.

The Bracero Program was a war-time measure by Mexico to support the allies with manpower that would free up other men for military duty. Because of the war, and Mexican support for the allies, the country was rapidly expanding industrial production, and… after the way… state policy favored industrial development and expanded commercial agriculture. During the War itself, as in the United States, women who had never been considered part of the work-force were hired in huge numbers.

Officially, Mexicans who were willing to fill jobs in the U.S. during the war were required to have a letter from their Presidente Municipal specifying that they were single men, for whom no work was available locally. However, on the US side, employers (especially commercial farmers) were also facing a labor shortage, and would just “assume” any Mexican worker who showed up was a Bracero, and … of course… word got back that there was work in the US, so people otherwise not eligible for the official program went anyway.

Post-war, the popularity of working in the United States (generally as a temporary way to augment family income at home) continued (both for Mexican workers, and for U.S. employers), and — as in the U.S. — the women factory workers were let go… creating a perceived labor shortage for Mexican employers. Coupled with this, the Mexican Foreign Secretariat considered the “official” Braceros worthy of their concern (and Mexican consuls were demanding U.S. employers and the U.S. government protect the labor rights of those workers), Mexican nationals who were not in the official program were considered “disloyal” to the Republic, and received no protection from their government.

Post-war, the popularity of working in the United States (generally as a temporary way to augment family income at home) continued (both for Mexican workers, and for U.S. employers), and — as in the U.S. — the women factory workers were let go… creating a perceived labor shortage for Mexican employers. Coupled with this, the Mexican Foreign Secretariat considered the “official” Braceros worthy of their concern (and Mexican consuls were demanding U.S. employers and the U.S. government protect the labor rights of those workers), Mexican nationals who were not in the official program were considered “disloyal” to the Republic, and received no protection from their government.

Read it!

Operation Wetback, the 1950s immigration policy Donald Trump loves, explained

Again?

Initial reports had 50 MORE Ayotzinapa students missing appear to be premature. According to reports (and there is video evidence), about 600 police, mostly state police, attacked a convoy of 250 normal school students traveling in seven buses about five P.M. Wednesday evening. Police in chase vehicles can be seen smashing windows in the buses, and hurling tear gas canisters inside.

The fifty or so missing students … this time… may be detained by the police, may be injured and seeking medical attention… or… as happened a year ago September, may be been “disappeared” . The pro-government Milenio is claiming the students had pipe bombs, and 13 were arrested, which still doesn’t explain the attacks on the buses, nor the violence of the confrontation.

Searching for Pancho Villa… et. al.

It’s often said that the first casualty of war is the Truth. Perhaps the final casualty is our memory. Although the Mexican Revolution was much more than a military conflict (in reality, a series of military conflicts) involving radically conflicting visions of what it meant to be a nation in the 20th century — the forerunner of both the better known European ideological conflicts beginning with the Russian Revolution, and of the later struggles against colonialist and neo-colonialist exploitation — our “memory” of what happened a century ago is rooted in what was memorialized at the time.

But images of ideological struggles are likely to be rather dull, and do not capture the public imagination the way those of armed conflict do. Although wars had been photographed as far back as the American Civil War, and there was always a market for such images, moving pictures were still something of a novelty in 1910 when the first phase of the Mexican Revolution, conveniently close to the United States border, created an ideal climate for presenting at least a vicarious look at war for those safely distant from the realities of the conflict. Until 1917, when the United States entered the European “Great War”, U.S. audiences were positively thrilled to follow the conflict “south of the border” at movie houses and theaters. Pancho Villa, as everyone knows, signed a contract with The Mutual Film Company, to have a film made about his life and struggles. That film played throughout the United States, at “premiere” venues (sometimes charging the then outrageous price of $2.00 a ticket — about $50 today) for a glimpse of Villa and his army.

While “The Life and Times of Pancho Villa” is probably the best known film of the era, there were others, and Villa was not the only caudillo to recognize the propaganda power of the new media. Zapata, Obregón, and even Victoriano Huerta cooperated with foreign film crews: Huerta, perhaps ahead of his time, offered to rent out the entire Federal Army to film directors seeking to make epic war pictures Made mostly by U.S. companies, while we see today only clips and segments of the films, the stories they told reflect the contemporary U.S. perspective of Mexico… while, simultaneously, creating impressions of Mexico that last to this day. The creative and progressive upheavals of the Revolution were washed out by cannon fire and lost in a wilderness of cactus and desert landscapes. Although some European directors also tried to tell the story, they too, imposed their own meanings on the Revolution. A Dutch film of 1916, with a pro-British slant, played up the story of the Zimmerman Note, and portrayed Mexico not as a nation fighting for its own identity, but as a pawn in the European conflict.

And then… with audiences turning their attentions away from Mexico… or — having seen the Mexico projected by what was then “mass media” forgot all but the stereotypes. The films themselves were forgotten, and — their commercial value reduced by changing audience demands — scrapped.

Directed by Gregorio Rocha, and produced by the University of Guadalaja, “Los rollos perditos de Pancho Villa” explores the search for the missing Villa film through archives and collections in Mexico, the United States, Canada, and Europe. Along the way, researcher Frank Katz uncovers scraps and pieces of other unknown films, telling the story of the story of the imaginings of the seminal event in Mexico history.

Sombrero tip to Tony VillaZapata, who uploaded this film in four videos.

Here kitty, kitty, kitty…

Never mind that within the last few days there have been six homicides and an earthquake in Coyuca de Benitez, Guerrero. What has people rattled is a missing kitty.

Ankor, an orange striped kitty has been missing from his usual spot at the Hotel Paraíso, and is probably somewhere in the mangrove swamps.

Did I mention he’s a rather large kitty?

Ankor… a Bengal tiger… hasn’t been going hungry, having eaten at least four kids (uh… goats, not humans) since heading into the swamps last week. I’m sure he’s doing fine.

Day of the dead

Time to strip away our illusions…

Our confused expats

Oh my…

I am sure these cute tykes had a wonderful time at their HALLOWE’EN party, but they obviously were not part of any DÍA DE LOS MUERTOS celebration that I’ve ever seen or experienced. The first started as a Celtic end-of-summer festival, and while somehow connected to witches and goblins, and … later to disguises and tricks, Día de los muertos is rooted in Indigenous American custom, overlaid with Spanish Catholicism. While I’m perfectly aware that customs cross-fertilize, and that the two quasi-holidays coincide (thanks to moving the mesoamerican holiday to a date that fits the liturgical calendar) confusing them seems an act of cultural imperialism.

While Día de los muertos, despite the recent innovation of costuming (although, the mesoamericans did have special outfits worn to imitate the dead), Halloween — in its modern, US version — has more to do with Carnival than anything else in our traditions… what with the fantasy costumes and the rationale to eat, drink, and be merry (or… in some neighorhoods, Mary).

If one dresses for Halloween, the ideal is to come up with something individualized, whereas those who dress for Día de los muertos costume themselves for a communal ritual. As a group, whether the family, the parish, the community, we are coming together to express less grief as acknowledgement that, as humans, we will die and it is nothing to fear not to be frightened by. Oppose that to the U.S. holiday, which — for adults at any rate — is all about fright and fear of death. Or denial of death… witness the popularity of zombies and vampires at Halloween.

I hope the tykes in the facebook post above had a wonderful time. Perhaps they had some life-lessons in … what exactly? To trivialize our rituals, our past, our community, into some quasi-commercial celebration of the sugar industry, Hollywood horror, and personal eccentricity, undermines the culture. Día de los muertos is a communal activity, so maybe these kids did at least have to play nice. It is about sharing our world with the past… and maybe these kids had to share their “ritual foods” of candy corn and Snickers bars, but somehow that isn’t the same as accepting those from the past, and ourselves in the future, as part of a community, with whom we are still happy to break bread.

La llorona… our national ghost

Via Municipios de Oaxaca (sombrero tip to Sterling Bennett):

The classic ghost story, Llorona — her man having done her wrong — has either drowned her lover, or her children (depending on the version) and is condemned to wonder the earth, weeping for her loss.

Everyone calls me the woman who weeps

A morena, who was all too loving.

Everyone calls me “Llorona” the weeper

A morena, who was all too loving.

I am like the chile verde, Llorona

Burning, but oh so tasty

I am like the chile verde, Llorona

Burning, but oh so tasty

They say that I feel no remorse, Llorona

Because they have not seen me cry

But the dead keep their silence, Llorona

So much greater is their pain

Oh, speak to me Llorona, Llorona

Llorona, here at the river.

Cover me with your rebozo, Llorona

I am so cold, so cold…

A plague of locusts?

The “Prophet of the Most High God Jehovah of the Army”, Juan Hernández López, is warning that San Cristobol de las Casas needs a name change… or else.

The “or elses” are detailed in a letter sent to San Cristobal’s municipal president, Marco Antonio Cancano Gonzales, dated 23 September, warning that if the city’s name was not changed (along with “converting” the municipal palace into a shrine to said “Most High God”) to “Ciudad de Jehová de los Ejércitos”, there was a risk of

- tornados

- earthquakes

- hurricanes

- giant hail strikes

- drought

- floods

- a plague of locusts

- meteorites

- and… a tsunami.

While we are just hearing of this immanent threat now, I suppose one might want to be warned that San Crisobal (about 200 Km from the Pacific, and 300 Km from the Atlantic Ocean). Watch out for falling meteors.

(Emeeques)