The cartel we don’t talk about

The United States today spends more money each year on border and immigration enforcement than the combined budgets of the FBI, ATF, DEA, Secret Service and U.S. Marshals—plus the entire NYPD annual budget. Altogether, the country has invested more than $100 billion in border and immigration control since 9/11.

It has paid for quite a force: Customs and Border Protection not only employs some 60,000 total personnel—everything from desert agents on horseback to insect inspectors at airports—but also operates a fleet of some 250 planes, helicopters and unmanned aerial vehicles like the Predator drones the military sent to Iraq and Afghanistan, making CBP both the largest law enforcement air force in the world and equivalent roughly to the size of Brazil’s entire combat air force.

The Green Monster: How the Border Patrol became America’s most out-of-control law enforcement agency.

By Garrett M. Graff, Politico.

Not taking on a tank, still…

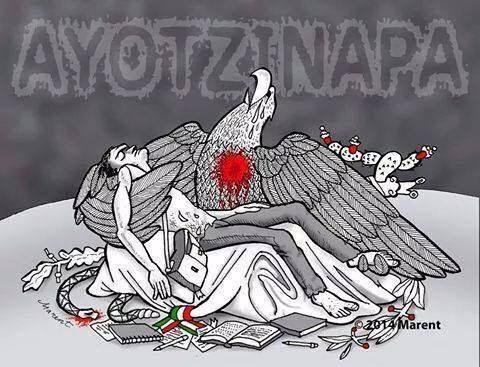

Ayotzinapa: “Tell us what to do”

OME POALI UAN YEI

Ontlahtlani to tonaltzintli, kemania mo nextihtzinoz?

In to tiotzi Texcatlipocatl chokatinemi, aka kuili I pipiltotzin

Zeki kihtohua oyehke omepoali uan yie, ipan Ayotzipan,

Uan okzekime mo polihtimeni ipan okzeki hueyi altepeme.

Non tlen or tech tlahtolmaka, or tech nahuati

Mo xokoyotzin cuahutemotzin,

Tik chian in tonal mo mahuizotzi ti kizaz

UAN hiki ti mo chihchihuazke, xikita ti kahkokihke in tletl itech in tocha

Ximo nexti tonaltzin.

SPEAK TO US, TELL US WHAT TO DO

We are biding our time… oh when will you return?

Great-Grandfather, Texcatlipocatl join in mourning our stolen children.

Some say it was forty-three taken from Ayotzinapa

And we know not how many others elsewhere.

Speak to us, we will follow your advice

To the last of your sons, Cuahutemotzin,

We await the day we go forward.

Strengthen us, looking to keep the fire inside our homes,

Until you reveal yourself to us, oh Great Sun.

(Apologies to Irwin — Rescantando Al Idoma Nahuatl — for the very loose translation … or rather attempted reworking, via a Spanish translation and a Nahautl cribsheet — of the original)

Oh, Canada… how could you?

Sandra Cuffe, “Blood for Gold: The Human Cost of Canada’s ‘Free Trade’ With Honduras” (Upside Down World, 13 November 2014)

Communities throughout the country have seen the legacy of devastation in the Siria Valley, and many Hondurans share Arteaga’s perspective on what Canadian mining companies have to offer. “What interests them is getting rich, filling their pockets with money and taking it out of the country,” he says.

The Canadian government has been on a roll promoting the interests of Canadian extractive industry corporations in Honduras in the five years since democratically elected president Manuel Zelaya was ousted in a June 2009 coup d’état. Development aid, embassy resources and foreign affairs programming have all helped set the stage for new legislation conducive to Canadian corporate interests, and a new bilateral free trade agreement provides protection for their investments.

The Canada-Honduras Free Trade Agreement came into effect on Oct. 1, 2014. Canada had originally planned to negotiate a regional free trade agreement with Honduras and its neighbours, Guatemala, Nicaragua and El Salvador. After nearly a decade of stop-and-start talks, Canada opted to pursue a bilateral agreement with Honduras in 2010, less than a year after the coup. The deal was announced during an August 2011 visit to Honduras by Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper, the first head of state to visit the country after its readmission into the Organization of American States two months earlier.

The free trade agreement, though, is just one recent element of Canada’s promotion of its business interests.

“In Honduras, Canada’s use of overseas development aid and its diplomacy to promote corporate interests are really evident, particularly in the immediate aftermath of the military-backed coup in 2009,” said Jennifer Moore, Latin America program coordinator at MiningWatch Canada.

It appears I’m not the only one riffing on this… the militarization of “free trade” (neo-liberalism, or corporate control or plain old colonialism… by a bunch of ex-colonials). I suppose Canada being a smaller power than the U.S., it’s natural it goes after smaller targets, but the result is the same.

Burning down the (state) house

Perhaps the Guerrero political establishment will get the message now that angry students, parents, teachers and fed up citizens torched the state legislature:

Via RT:

My comment: Democracy is messy, and, as Winston Churchill once said, the worst form of government, except for all the others.” It seems political parties… an 18th century idea… exist mainly to perpetuate themselves, and when they are not particularly ideological, or one’s choices are limited to existing political parties, I can understand exactly why citizens feel they are useless and resort to democracy by less genteel means.

In Mexico, after the “democratic opening” of the late 1980s (in good part in response to both the citizens forced to act for themselves after the 1985 Earthquake, as well as the threat of an uprising after the stolen 1988 Presidential election) there were any number of ideological parties, but there has been a continual push by the main parties to force out the minority parties. The threshhold for ballot access has been continually raised, and… financing for electioneering has been tilted towards the three major parties. While not quite as bad as in the United States, where campaigns are openly run through bribery and access is limited in nearly every state to two neo-liberal parties, the Mexican party system is broken, and there is talk of how to fix it.

That seems a mistake. Why go with an 18th century political concept? Why, for that matter, elect legislatures by geographical region, instead of, say, social interest or economic class? Certainly, the technology exists for counting ballots in proportional representation elections… why not let people chose three or five (or whatever) interest fields, and elect representatives for their interests? If 50& of Guerrero’s voters choose to vote for a campesino candidate, and 20 percent for a business candidate, and 2 percent for an environmentalist, and the rest for any number of special interests, why not a legislature reflecting what the people actually want?

Or why not some other form of democracy? Why stick to 18th century forms?

Other ideas?

The more than drug “war”

“The whole process of arming NAFTA means that there’s a series of mechanisms (the drug war being the most important) that are really aimed at militarizing the country in order to protect foreign investment,” explains Laura Carlsen of the Center for International Policy.

“We know is that the United States is funding this drug war to support security forces that, it turns out, are in deep collusion with the criminal forces — and this collusion is directed against the population.”

I have little patience … as in absolutely none… with those naive north of the border commentators on every story about some atrocity here in Mexico reading “if they just legalized drugs, the problem would be solved”. First off, because the “they” haven’t yet, and until “they” do, EVERY U.S. DRUG CONSUMER IS COMPLICIT IN MURDERING MEXICAN PEASANTS AND STUDENTS.

While it certainly would be intelligent to legalize the narcotics trade, the USAnians who believe this are no different, really, than those who insist the U.S. is ENTITLED to the agricultural products, minerals, oil, labor and water of other people for no reason other than… I don’t know, military power maybe?

That said, I am glad to see the phony “drug war” discussed for what it really is… a war against Mexican (and anyone else’s) reasonable expectations that their natural resources are their own, and that as human beings, they have a right to live their lives, and make decisions in their own best interests, not those of foreign consumers and corporate interests:

Moving Day

The tequila effect?

Is anyone in Mexico NOT angry right now?

NAFTA means wage stagnation….

Fascinating! From , “TRADE: The Nafta Paradox,”, Berkeley Review of Latin American Studies, Spring 2014.

Two interesting points. First, that the Mexican left was correct in 2006, when they (meaning AMLO) identified expanding the internal market as essential to improving economic conditions within Mexico, and second, that U.S. workers are right in “blaming Mexico” for stagnant wages… but only because Mexican wages have been stagnant, “thanks” to anti-union provisions within the NAFTA agreement.

..sharply expanded trade has brought benefits to Mexico, although it has hardly been the “undeniable success story” that some herald. Mexico has gained much-needed jobs, access to advanced production technology, and new ways of organizing work. However, only 3 percent of border plant exports are sourced domestically, and a mere 0.4 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) is invested in research and development. Moreover, low wages diminish purchasing power, limit the domestic market, and slow Mexico’s potential growth. Carol Wise points out that Mexico’s per capita income remains mired at “about one-third that of the wealthier countries in the OECD [Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development].”

The United Nations Development Program concluded in a 2007 report that, “Nafta has produced disappointing results in terms of growth and development.” Economists Gerardo Fujii Gambero and Rosario Cervantes Martínez writing in the April 2013 issue of the UN Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean Review found that “the gap between exports and GDP [in Mexico] has been widening, which indicates that the export sector is underperforming as a driver of economic growth.” They argued that “the ability of exports to galvanize the economy will be heightened if export activity leads to an expansion of the domestic market.”

Rising Productivity and Declining Wages

While very different economies, the United States and Mexico share similar problems: sharp income inequality, slow growth, high unemployment, and persistent underemployment. These problems are exacerbated by a troubling paradox: rising productivity combined with falling real wages. As a result, much of the economic gain has flowed to the top as workers and communities have faced downward pressure on wages and working conditions. While this productivity/wage disconnect emerged as a key issue during the Nafta debate, it now feeds into a growing concern in many countries throughout the world, including the United States, about the corrosive effects of economic inequality, which President Obama has called the defining issue of our time.

Mexican Productivity and Compensation, 1994-2011

![]()

Labor Productivity & Median Real Hourly Compensation for Workers in Manufacturing (1994=100)

Sources:Encuesta Industrial Mensual (CMAP). Banco de Información Económica (BIE), Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI).

Consider the dimensions of this disconnect in Mexico. Mexican manufacturing productivity rose by almost 80 percent under Nafta between 1994 and 2010, while real hourly compensation — wages and benefits — slid by nearly 20 percent. In fact, this data understates the productivity/wage disconnect. Wages in 1994, the base year, were already 30 percent below their 1980 level despite significant increases in productivity during this period. Although they are producing more, millions of Mexican workers are earning less than they did three decades ago.

Economists often maintain that if wages are low, their level simply reflects low productivity. In the Mexican case, however, low wages exist in spite of strong gains in manufacturing productivity. These low wages reflect a number of factors, from government policy to globalization, but a central issue is the lack of labor rights in the export sector. As a result, it is difficult to form independent unions that can exert pressure to restore a more robust link between productivity and wages. If workers are unable to share in the gains, high-productivity poverty becomes a danger. The damage affects more than Mexican workers. The gap between productivity and wages results in low purchasing power, which depresses consumer demand and slows economic growth.

This gap in Mexico also puts downward pressure on wages in the United States, contributing to a U.S. wage/productivity gap that began opening up in the mid-1970s. Between 1947 and the early 1970s, strong unions forged a link between rising productivity and higher wages, and the entire economy benefitted. As union strength waned, the U.S. wage/productivity gap opened and wages stagnated. What does this have to do with Nafta? A key question during the Nafta debates in 1993 was whether Mexican and U.S. wages would harmonize upwards or be pulled downwards by the agreement. Proponents argued that expanding trade alone would lift all boats, while critics maintained that effective labor standards were essential to insure that everyone would benefit.

Chomsky on Latin America

From an interview by Greg Granden, published in The Nation (31 October 2014):

GG: Immigration from Mexico and Central America is an issue that, in the United States, reveals the close connection between domestic and foreign policy. Do you see this as one potential source of hope and resistance?

NC: To this moment, Mayans are fleeing from the consequences of the virtual genocide of the 1980s, primarily at the hands of José Efraín Ríos Montt, whom the historian Stephen Rabe describes accurately as “the Guatemalan butcher who supervised the eradication of 100,000 mainly Mayan people”—or, if we prefer, a man “of great personal integrity” who was getting a “bum rap” from human rights groups, according to the boss in Washington, whose spirit now hovers over us like “a warm and friendly ghost” in the Kim Il-sung–style renditions of Hoover Institution scholars. The flight of Mexicans was anticipated: Clinton initiated the militarization of the border when NAFTA was passed. It was quite predictable that NAFTA would destroy much of the campesino class, unable to compete with highly subsidized US agribusiness, along with other effects by now well-documented. Immigration follows as night follows day. Much the same is true throughout the region. The consequences of these policies engender conflicts within the United States. Super-cheap and highly vulnerable labor is a boon to business. But it is perceived by the white working class as a threat to its subsistence and cultural values, which are already felt to be under threat for many reasons, even more so as whites will become a minority in the not too distant future. These tendencies are being exploited in ugly ways by political leaders who are dedicated to service to the “1 percent” but need a voting constituency. That’s been the natural decision of strategists for the Republicans, who put aside any pretense of being a traditional parliamentary party long ago, also shedding their moderates. Now centrist Democrats are following not too far behind.

NC: To this moment, Mayans are fleeing from the consequences of the virtual genocide of the 1980s, primarily at the hands of José Efraín Ríos Montt, whom the historian Stephen Rabe describes accurately as “the Guatemalan butcher who supervised the eradication of 100,000 mainly Mayan people”—or, if we prefer, a man “of great personal integrity” who was getting a “bum rap” from human rights groups, according to the boss in Washington, whose spirit now hovers over us like “a warm and friendly ghost” in the Kim Il-sung–style renditions of Hoover Institution scholars. The flight of Mexicans was anticipated: Clinton initiated the militarization of the border when NAFTA was passed. It was quite predictable that NAFTA would destroy much of the campesino class, unable to compete with highly subsidized US agribusiness, along with other effects by now well-documented. Immigration follows as night follows day. Much the same is true throughout the region. The consequences of these policies engender conflicts within the United States. Super-cheap and highly vulnerable labor is a boon to business. But it is perceived by the white working class as a threat to its subsistence and cultural values, which are already felt to be under threat for many reasons, even more so as whites will become a minority in the not too distant future. These tendencies are being exploited in ugly ways by political leaders who are dedicated to service to the “1 percent” but need a voting constituency. That’s been the natural decision of strategists for the Republicans, who put aside any pretense of being a traditional parliamentary party long ago, also shedding their moderates. Now centrist Democrats are following not too far behind.

There is indeed resistance, a reason for hope, but the prospects will be grim if the US socioeconomic and political system persists in the vicious cycle that became established in the 1970s and escalated since, with a sharp concentration of wealth (increasingly in the financial sector) leading reflexively to concentration of political power and legislation to carry the cycle forward. It’s not inevitable by any means. There are encouraging signs at last of popular opposition, notably in the Occupy movements. But there is sure to be hard struggle ahead.

(Sombero tip: Bill Wilson, San Miguel Allende)

Charles, Camilla, and…

Lady Died?

Photo: Getty Images, via Hello (GB)

The British heir to the throne is on a state visit to Mexico… not that anyone particularly cares about it.