Makes sense to me…

Cometín… aka Esteban Sánchez is seeking to represent a blue-collar/poor district in Sinaloa. As a candidate for the left-wing populist Citizen’s Movement, Sánchez’ campaign is arguing that neighborhoods like his are ignored by the clowns in the legislature, except when they come begging for votes. In other words, your usual better street lights, garbage collection, safe schools type of campaign.

Cometín… aka Esteban Sánchez is seeking to represent a blue-collar/poor district in Sinaloa. As a candidate for the left-wing populist Citizen’s Movement, Sánchez’ campaign is arguing that neighborhoods like his are ignored by the clowns in the legislature, except when they come begging for votes. In other words, your usual better street lights, garbage collection, safe schools type of campaign.

Criticized by a former party leader (now with the conservative PAN) for making a mockery of politics, Sánchez’ personal story — that of an orphan and street kid who took advantage of a public education to develop a trade that supports himself and his family — resonates with his constituents, and candidacy is taken seriously enough by his opponents for him to receive death threats, which has made for a sad clown, but not one to be laughed at.

Revenue enhancement, the old fashioned way

I don’t think we’d ever sell A History of Lower California (The Only Complete and Reliable One) by Pablo L. Martinez, translated by Ethel Duffy Turner (widow of John Kenneth Turner), self-published in an edition of 3000 by the author in 1960. So, I just took it home.

While perhaps it is “the only complete and reliable” history of the Baja up through 1960, it wasn’t exactly the most exciting of reading (which … my sleep cycle being off… was kind of the point). Still — despite the bad writing (and, I am afraid, rather clumsy translation) — there were a few eye-opening passages.

Sent to Mexicali to put down the short-lived and doomed anarchist uprising in the Baja in 1911, Major Esteban Cantú was nothing, if not flexible. A soldier in the service of Porfirio Díaz, he served the Madero government, supported Huerta (who, as a reward, promoted Cantú to Colonel and left him basically in charge of what is now Baja California Norte, but at the time was sub-district of the remote, largely ungovernable and under-populated territory of Baja California). With Huerta’s overthrow, and not quite sure the Constitutionalist government of Venustiano Carranza was going to be around all that long, Cantú basically ran an independent fiefdom.

With the back and forth fighting on the mainland, “Cantúlandia” more or less had to fend for itself, and for the first time in its history, was economically viable. From its late incorporation into Mexico (in the 1600s) up until the time Martinez was writing, the Baja’s history was one of a forgotten appendage. Under the Viceroys, it just wasn’t worth the time and expense of settling the place, so it was turned over to the Jesuits… who could only support modest developments by depending on outside income (Specifically, they set up an endowment fund of a sort… convincing wealthy supporters to buy the Society cattle ranches on the mainland, and dedicating the profits — at least in theory — to Church activities in California). When the Jesuits were expelled from New Spain, the Franciscans, and later the Dominicans, took a crack at turning the Baja into something more than a drain on the public treasury, to no avail.

The region’s post-independence history was mostly one of a financially unstable federal government only reluctantly sending a few troops when it could, and mostly forgetting about the place. That the country held on to the territory after the 1848 forced annexation of northern territories to the United States was more a matter of protecting the mainland states facing the Baja (Sinaloa and Sonora) from the U.S. than any concern for its inhabitants.

In the latter part of the 19th century, Don Porfirio’s governments did get some financial return out of the Baja, mostly by granting concessions to U.S. and British corporations seeking to “develop” the property in some way (usually convincing suckers that there was water out there). By Cantú’s time, the foreign companies (which, on paper, owned about 90 percent of what became Baja California Norte) and, other than a few small settlements along the coasts and the Colorado River, was still a desolate, economically marginal place.

What Cantú did… when he decided the Baja was “neutral” in the Mexican revolution (meaning he’d side with whoever won… maybe), was to keep on collecting federal taxes, but not send them along to the Capital, as well as impose some local taxes (including an income tax). Keeping the federal funds in reserve (which, in the end, is what saved him from being considered a traitor to his country), he is highly praised by Martinez for investing the state funds in development.

More amazing to me, is that despite the unsettled conditions in Mexico as a whole, Cantú’s irregular regime (1915-1920) was something of a golden age for education. Schools were built and teachers extremely well paid though fostering one industry where the Baja had a distinct advantage. Geographically and politically isolated from its own country, Cantú’s administration sought out products that it could export to the United States.

Narcotics.

As the new functionary encountered the land burned out, as the offical coffers were empty… he set about contrying [sic] to obtain funds, as a first measure, by collecting a duty on all national merchandise that entered the territory, just as was done with foreign goods. His second act was to impost a personal tax that lasted for a long time, even after the financial crisis of the moment was over. For the same purpose he opened gambling houses, prostitution increased rapidly, as well as the drug traffic, although for the time being this traffic was clandestine.

Abelardo Rodriguez, the future president, then an army general, was tasked with “convincing” the self-appointed Cantú to step down in 1920. Rodriguez was then put in charge of the territory (territorial governors being appointed by the President, not elected) and had the good fortune to come into office just as the United States had outlawed liquor. So… with Cantú having paved the way to financial security through whores and drugs, Rodriquez fostered the booze industry.

Martinez wrote that the worst blow to the Baja economy in the early 20th century was not the world-wide Depression of 1929, but the end of Prohibition in the United States in 1933. One wonders what he’d make of calls for an end to narcotics prohibition today.

How it was

It took me a minute to recognize this… I used to live just down the street.

The theater was across from the park in Santa María de la Ribera, in Mexico City. The building has been replaced with apartments and shops. Off to the right from the lady watching the little boy with the balloon (the photographer’s grandmother and younger brother) and across the street was the biggest shop in Mexico specializing in insects (you can find anything in Mexico City, if you aren’t looking for it!). Two or three doors down was the former home of Madre Conchita, the female Osama Bin Ladin of 1920s Mexico.

Then 12-year old Eduardo Molina Moysén took this photo in 1967 with his first camera.

And here it is today, on “Google Earth”:

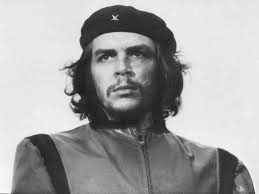

This epic before us is going to be written by the hungry Indian masses, the peasants without land, the exploited workers. It is going to be written by the progressive masses, the honest and brilliant intellectuals, who so greatly abound in our suffering Latin American lands. Struggles of masses and ideas. An epic that will be carried forward by our peoples, mistreated and scorned by imperialism; our people, unreckoned with until today, who are now beginning to shake off their slumber. Imperialism considered us a weak and submissive flock; and now it begins to be terrified of that flock; a gigantic flock of 200 million Latin Americans in whom Yankee monopoly capitalism now sees its gravediggers …. And the wave of anger, of demands for justice, of claims for rights trampled underfoot, which is beginning to sweep the lands of Latin America, will not stop.

(Che Guevara, to the U.N. General Assembly, 11 December 1964)

Ernesto Guevara Lynch, born 85 years ago today, in Rosario, Argentina.

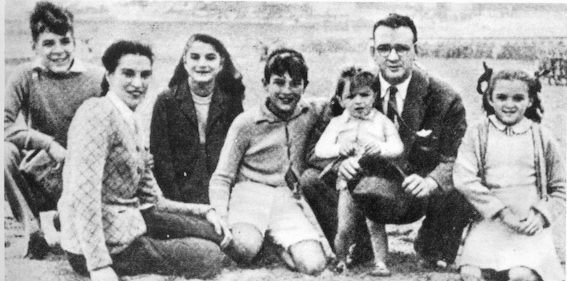

Che (on left) as a 16 year old geek, with (from left to right), mother Celia, sister Celia, brothers Roberto and Juan Martín, father Ernesto and sister Ana María.

There is an adulatory short biography on the Che Guevara blog, but for those looking for something more:

John Lee Anderson’s Che Guevara: A Revolutionary Life, is as complete as a U.S. author could be expected to write, based on mostly “official” sources and oftentimes almost apologetic for admitting there was a reason so many (especially in Latin America) see Ché as a legitimate critic of U.S. imperialism.

Two Latin American biographers (both Mexicans, as it happens), are better on capturing and considering the rootedness of Ché’s internationalism in his Latin American heritage, and both were able to access sources not available to Anderson.

Jorge Castañeda’s Compañero: The Life and Death of Che Guevara is probably the fullest English-language biography. Castañeda is faulted for on the one hand being overly-academic and on the other for portraying Guevara as ” nothing more than a spoiled child with delusions of grandeur throwing a temper tantrum” (in the words of one “Goodreads” reviewer).

While much more readable, and the product of a much better (and much more entertaining author), the English-language translation of Paco Ignacio Taibo’s Guevara, Also Known as Ché has more than its share of typos and awkward translations. It is, however, the best of the biographies, concentrating on Ché as an enduring touchstone in any consideration of Latin American (and international) confrontation with the great powers.

BRAINS!!!!!!

Diana Gómez, a chilango-born U.S. citizen, isn’t dead yet… but when she is, she’ll provide the “… the first bi-lingual latino brain to be studied in a laboratory.”

The Brain Observatory (University of California at San Diego) is doing serious medical research, and while they need all kinds of brains, they are also finding that Mexican provide the brains Americans can’t.

Un nuevo día

Por supuesto,los derechistas y los nativistas están siendo pendejos. ¿Porque?

The United States, being either the 4th or 7th largest Spanish speaking nation (depends if you include Puerto Rico, and if you accept all variant forms of Spanish, including the two or three dialects of Spanglish as Spanish) one shouldn’t be surprised that some of its most prominent citizens can speak the language of Cervantes. If you’re wondering, Senator Tim Kaine (D-Virginia) was a lay worker with the Jesuits in Honduras as a young man. What’s impressive is that he even used the body language of native speakers in his speech on the floor of the U.S. Senate earlier today.

Don Luis Mártinez y Rodríguez … the cunning linguist

An aside in a piece on a failed fascist colony in Baja California (Falange y sinarquismo en Baja California) in Sunday’s La Jornada by Hugo Gutiérrez Vega mentioned in passing the remarkable Don Luis María Martínez y Rodríguez, the 32nd Archbishop of Mexico City (1937 – 1956).

Don Luis was appointed Primate of Mexico as successor to the only Jesuit (and only American Indian) to hold that post, Pascual Díaz y Barreto, who had been instrumental in negotiating an end to the Cristero War. Don Luis’ appointment came at a crucial time in Mexican church-state relations, putting the Archbishop between a leftist anti-clerical government on one side, and a reactionary movement within the Church that was rapidly moving towards militant Fascism on the other.

Although known as a theologian rather than a political bishop, Don Luis proved to be the right man at the right time. With much of the conservative faithful enamored with Franciso Franco, while the Mexican state openly backed the Spanish Republicans and within some states open persecution of the church was still the order of the day, Don Luis in some ways faced similar problems to that faced by Jorge Mario Bergoglio when he was Archbishop of Buenos Aires.

Although “liberation theology” was far in the future, like now Pope Francis, Don Luis had to protect the church FROM the state on one hand, while holding off those within the Church who would politicize their faith (never mind that the roles were reversed — Mexico being a leftist state, with clerics involved in rightist politics, whereas Argentina had a rightist government and leftist clerics). Like Bergoglio, Martínez y Rodríguez saw his mission as keeping the church relevant to national affairs, while, simultanously, avoiding the danger of allowing one faction within the church to create a violent reaction against the state … which, in Mexico — having only emerged from a ten year civil war/revolution and a religiously inspired insurgent uprising — and the entire world on the brink of war … was all the more critical in the Mexico of the late 1930s.

As a theologian, and a gifted writer, Don Luis found common ground with the Cárdinas Administration in the social goals of the state and the social teachings of the Church. Don Luis crafted a religious justification for nationalizing the oil industry in 1938, which not only gave the Archbishop entre into state affairs, but — more importantly — signaled to the Catholic majority that even the “atheist” state might be morally correct. As to the Synarchist (Mexican fascist) movement, Don Luis made clear his objections to the movement (it was thanks to him that during World War II Mexican Catholics would largely support the Allies, despite Synarchist support for the Axis) and moved the most reactionary clerics out of sensitive positions within the Church. As a Bishop, Martínez y Rodríguez claimed he took his cue from the first Bishop of Mexico, Juan de Zumárraga (1530-1548), who Don Luis saw as fostering a Church meant to serve the people and cooperate with the state. He was quite willing to negotiate with the federal government for expanding the social service network and in support of labor rights.

Unusual among the post-Revolutionary hierarchy, Don Luis was highly regarded in by the usually anti-clerical intellectuals, not merely for his willingness to find common ground with the state, but also for his genuine gifts as a poet, linguist and wit.

As Primate, he sought to modernize the Church institutionally (setting up the first Diocesan Synod) and physically… seeing the restoration and modernization of church facilities throughout the country as a means of bringing the institution closer to the masses. Alas, things did not always go according to plan. When he had a sound system installed at the Basilica of Guadalupe, his inaugural sermon was memorable… not for it’s subject or rhetoric, but for its attention-grabbing opening statement. The microphone shorted, giving His Eminence a nasty shock, and the first words ever broadcast in the Basilica boomed forth: “¡Ah, chingao!“…. or, as we’d say in English: OH, FUCK!”

It was probably the only time Don Luis’ eloquence failed him. In 1950, not in recognition of his role in the oil nationalization, and certainly not in recognition of his work as a theological scholar, but in honor of his impossible to overlook work as a poet and linguist, Don Luis received a membership in the Academia Mexicana de la Lengua. While appointment to the Academia Mexicana, like corresponding insitutions of the Real Academia Española throughout the Spanish-speaking world, is largely a way of honoring scholarship, the members take their task of defining and setting the standards for the proper use of the Spanish language quite seriously.

Naturally, as a Roman Catholic cleric, Don Luis was considered the go-to guy for proper definitions for Latin words used in Spanish. Rather waggishly (and with a hint of anti-clericalism) , one of his fellow academicians requested His Eminence to define “cunnilingus”… which His Eminence did, quite gracefully and without, apparently, a second thought: “A pious contemplation of the place where man emerges into this world, often performed while kneeling“.

Don Luis has been proposed for beatification, the first step in the Catholic church towards official sainthood. And why not? It only takes “heroic virtue” to be Beatified… and there’s something virtuous (and heroic) in not just working with the people and building churches, but in writing well, and having a quick wit.

Hiding in plain sight?

Andres Granier disappeared his last day in office as Governor of Tabasco… along with the state treasury, an estimated 23 Billion pesos (about 1.8 Billion US$).

It’s not so much that Granier was a mega-thief, as that he managed the unforgivable sin of not passing along the governorship to the PRI candidate in Tabasco that has made him a toxic asset to the Peña Nieto administration.

While the new PRD administration in Villahermosa (Tabasco’s state capital) has managed to find a few million in missing state funds (in cash… sitting in a former state treasury official’s bedroom closet) , the feds have only now issued an all points bulletin for Granier. He’s probably in Miami, where Latin America’s biggest crooks can usually be found.

Traditional values: reading García Marquez

Looking for an authentic Mexican folk-custom?

The ejido of Recoveco (Mocorito, Sinaloa) are celebrating the 66th anniversary of the founding of commune’s founding this weekend, with the traditional marathon reading of Gabriel García Marquez’ 100 Years of Solitude by the students of Rafael Buelna Tenorio Ag-Tech High School.

Recoveco (whose name means “bend in the road”, by the way) only adopted the marathon reading as a part of their annual celebration six years ago, but it has proven popular and was embraced by the 1600 or so residents of the farming and fishing commune as a traditional community event. Helping to foster Mexican traditional culture, Editorial Diana — the Mexican publisher of Gabriel García Marquez — has given the school library 50 new copies of the novel… one for every 32 residents f the farming and fishing community of 1600.

“Remedios la bella”, Mi Librería (la Habana, Cuba): http://milibreria.wordpress.com/2010/01/05/una-segunda-lectura-a-cien-anos-de-soledad/

Mexico’s beef with American beef

Is this a bad thing?

Via Reuters:

Mexico’s Economy Ministry said on Friday it was considering suspending preferential trade tariffs with the United States for a variety of products in a simmering dispute over meat labeling.

The disagreement stems from a 2009 U.S. requirement that retail outlets specify the country of origin on labels on meat and other products in an effort to give consumers more information about the safety and origin of their food.

Canada and Mexico have complained to the World Trade Organization that the COOL (country-of-origin labeling) rules discriminated against imported livestock.

The trade body ordered the United States to comply with WTO rules by May 23, but the U.S. government made revisions that Canada and Mexico say would only make the situation worse.

Mexico and Canada are seeking the WTO’s support in their case and the Mexican Economy Ministry said if the U.S. government is found to be in the wrong, Mexico would react.

Mexico and Canada are seeking the WTO’s support in their case and the Mexican Economy Ministry said if the U.S. government is found to be in the wrong, Mexico would react.

For this reason, the ministry said in a statement it was considering suspending preferential tariffs for a broad variety of produce including fruit and vegetables, juice, meat, dairy products, machinery, furniture, household goods, among others.

I’m something of a minority in saying this (at least among foreigners in Mexico), but dropping tariffs on U.S. agricultural imports was probably the worst things that’s happened to this country in this millenia. And that definitely includes the so-called drug war. If anything, it was flooding this country with subsidized U.S. agricultural products that forced rural Mexicans to turn to narcotics exports as one of the few agricultural exports that could compete in the “free market” (you know… allowing U.S. corporate farmers — with export tax credits, fuel subsidies and corporate tax breaks — to “compete” with small producers who lost their price guarantees. And, the alarming rise in diabetes and obesity, as cheap junk food from the U.S. has replaced the relatively nutritious (or at least non-frutose based) Mexican junk food.

So, where’s the Hope and Change?

There are no coincidents

TUCSON — The nation’s largest military contractors, facing federal budget cuts and the withdrawals from two wars, are turning their sights to the Mexican border in the hopes of collecting some of the billions of dollars expected to be spent on tighter security if immigration legislation becomes law.

(As Wars End, a Rush to Grab Dollars Spent on the Border, Eric Lipton, New York Times, 7 June 2013)

The House of Representatives on Thursday passed a $39 billion Department of Homeland Security spending bill for next fiscal year that would boost its funding by nearly $1 billion, shifting deeper cuts into other domestic agencies.

The measure passed on a 245-182 vote largely along party lines in the Republican-controlled chamber…

(House votes to boost homeland security spending, David Lawder, Reuters, 6 June 2013)

I’ve been saying for year that the “War on (some) Drug (Exporters)… and on Latin Americas” has less to do with stimulants than with stimulus.