Something wrong?

I don’t ask this lightly, but is there something seriously wrong with Enrique Peña Nieto?

Here he is in March 2011:

And here in three recent photographs:

Granted campaigning is hard on a person, and there wouldn’t be anything unusual about a man going gray rapidly at age 46 (or having dyed his hair during the campaign to present a youthful appearance as a candidate, but to opt for creating the image of a “mature” head of state). And, with the stress that has to come with the questions about his election… there might be some visible signs — although it wouldn’t be reassuring to his supporters to make note of the fact that the uncertainty is taking its toll.

But seriously… Mexican candidates aren’t under the microscope like U.S. candidates are and very few questions were raised about the private lives of any of the candidates. Or their health. Political journalist Rafael Loret de Mola mentioned back in October 2011 talk within the PRI about Peña Nieto’s “secret illness”… presumably prostate cancer.

While certainly a treatable illness, and certainly treatable in Mexico, it is known that Peña Nieto made at least 15 trips to Miami for medical treatment between January 2010 and February 2012. The PRI primary election was 5 February 2012, after which trips out of the country would have been more likely to be reported in the national press.

It should be pointed out that Loret de Mola is not a knee-jerk anti-PRI writer by any means. He has a family connection to the party, and his son, journalist and TV commentator Carlos Loret de Mola, has been widely criticized by the opposition parties and press as a cheerleader for Peña Nieto. Rafael’s father, also Carlos Loret de Mola, was a journalist turned politician, governor of the Yucatan running as a PRI candidate from 1970 to 1976. However, Rafael Loret de Mola has always contended that his father’s death in 1986 was not a car accident, but the assassination of a dissident PRI leader.

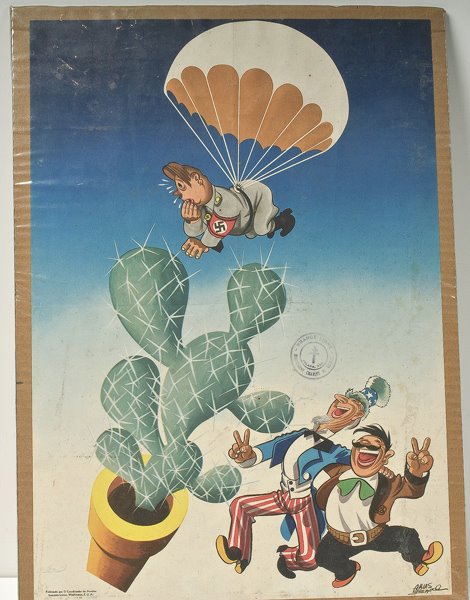

Wartime propaganda posters

There are several propaganda posters from the “Guerra contra nazifascismo” (Mexico’s only foreign war) at the link… but this one is my favorite. Mexico has had a great graphic arts tradition, and after the Revolution saw the arts and the visual arts were seen as vital to promoting state ideology.

Considering Great Britain had broken relations with the Mexican government in October 1938, and trying to lead an economic boycott against the Republic following the oil expropriation, and the general perception of the British as imperialists and exploiters, the pro-British posters are also worth noting:

There were serious attempts by the Nazis to infiltrate Mexico — but, Mexicans being Mexicans, how could they not see the funny side of it?:

One last drink with Chavela

María Isabel Anita Carmen de Jesús Vargas Lizano — Chavela Vargas … “the lady in the red poncho”… may not have been born in Mexico (14 April 1919, San Joaquín de Los Flores, Costa Rica), but she “owned” Mexican traditional music — the sentimental, sad ranchero and cantina songs — like no one else.

Although internationally recognized in her later years, Vargas was never wealthy, and never particular cared about conventional recognition. Her weary and worldly-wise stylings were less art and more heart.

A street singer up into her 30s, she only began to achieve fame when her friend, the composer José Alfredo Jiménez, convinced her to come into the recording studio. Chavela OWNED Jiménez… her version of his popular songs from the 40s and 50s and 60s becoming canonical in every cantina in Mexico. This despite the “macho” sensibilities of the songs, and the novelty of a woman singing ranchero.

Never much for convention, and one who cared more for her music than what one thought of the singer, Vargas came out as a lesbian at the age of 81 — just as she was becoming an icon and international superstar. If her promoters and booking agents were worried about the effect this might have on her fan base, they didn’t understand Mexico. Mexicans, even the most reactionary cantina louts, were not about to lose everyone’s favorite drinking buddy, their compadre who happened to be a woman.

And what a woman.

Chavela died earlier today in Cuernavaca.

The other Mexican on the Titanic

Manuel Uruchutu, who supposedly gave up a seat on the lifeboat to an English lady — earning a reputation as the archetypal Mexican caballero — was not the only Mexican to go down with the Titanic.

Most of what is published about Uruchutu comes from a single source, Guadalupe Loeza’s El Cabellero del Titanic (Aguilar, 2012) based on research by Uruchutu’s grandson, Alejandro Gárate Uruchutu.

Dave Bryceson, wrote the biography of Elizabeth Ramsdel Nye, the lady said to have been given a seat by Don Manuel. Messers Bryson and Gárate have a … uh… lively disagreement about what actually happened aboard the Titanic. Bryceson questions whether Mrs. Nye and Lic. Uruchutu even met.

Whatever the cold hard facts (other than the ship hit a cold hard object in the Atlantic Ocean), the storyline — the Mexican gentleman who gives up his seat to a lady, even though it will cost him his life — is probably more important for what it says about the way Mexicans see themselves, and what they consider national virtues.

Although I am not going to insert myself into the controversy among Titanic scholars over these two passengers, I am something of a Bryceson partisan for another reason. In the course of his research, he uncovered the existence of a second Mexican lost on the Titanic, and one who in some ways, is as much an archetypal figure, and an honorable one, as the Caballero Mexicano.

Antonio Ferrary, unlike Manuel Uruchurtu, was not an educated gentleman, nor someone who would be likely to travel first class. He was however, a heroic figure and one more likely to represent a “typical” Mexican … the working class immigrant doing a dirty, thankless job… and whose obscure death may not have involved some noble gesture like Uruchutu is said to have given, but was in its way, the more heroic.

Like working men throughout history, Antonio was not someone whose life would be minutely scrutinized. The Encylopedia Titanic only says he was born in Mexico in 1879, and his father was a butcher. His father’s name is given as “Louis”, which I assume is either a misprint for Luís… or that his father was an immigrant himself, who had half-Hispanicized a name like Ferry or O’Farrell. There is no record of Antonio in the 1901 British Census, so presumably he emigrated to England after that time. He seems to have been a “typical” workingman’s trade… an abañil. Or, at least when he married his boss’ daughter in 1908, his trade was listed as “plasterer”.

What makes it hard to track down Antonio is the possibility that he was also another archetype… an “illegal immigrant.” His wife, Annie, filled out the 1911 census form, listing Antonio as “Thomas” and claiming he was a U.S. resident. By then, he also had two children to support, and apparently — again typically Mexican — had changed his profession, becoming a “trimmer”… literally, a dirty job that somebody’s gotta do:

The ‘down-below’ seamen were responsible for working the boiler rooms and their adjacent coal bunkers. Collectively, they were known as the ‘Black Gang’, a term that lasted well into the diesel era. Strictly speaking, ‘Black Gang’ referred to the trimmers and firemen – the men in the stokeholds and the bunkers. ‘Stoker’ and ‘fireman’ are two different titles for the same job, but the term ‘fireman’ is almost exclusively used on ships. The normal ‘Black-gang’ might consist of six firemen, two trimmers and a ‘peggy’; altogether, on a ‘3-watch’ ship, a total of 27 men.

‘Trimmers’ have always been needed because the firemen require a constant supply of coal. Even lower in social crew status than the men they served, they bunked and messed separately. ‘Trimmers’ have always had the dirtiest and the most physically demanding jobs on the ship – the absolute bottom of the engineering hierarchy. Needless to say – they received the lowest pay.

Still, they did their job. As Bryceson said in an e-mail to me, it was an important one, a suicidal one, but had they not been continuing to work as the ship went down, the death toll would have been much higher, and people like Mrs. Nye would never have had the chance to be offered a seat in a lifeboat:

… Very few trimmers made it out alive. They would have been busy helping to dampen the fires in the boilers to prevent explosions and helping to ensure that the electricity supply remained on for as long as possible to aid those who did make it to the lifeboats. To drown in the dark – not the best of ways to die.

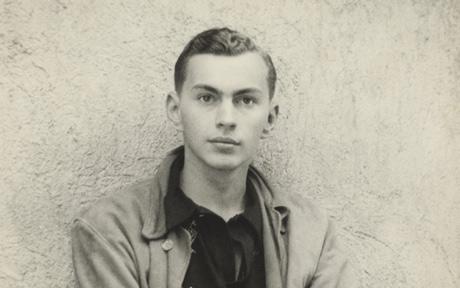

Interestingly enough, there MAY be a photograph of this unknown Mexican hero. Father Frank Browne, an Irish priest and enthusiastic amateur photographer, had been given a ticket on the Titanic by his uncle the Bishop. Although Father Browne had a first class ticket, as a clergyman and as an insatiable photographer, he roamed over the entire ship during what what be an abbreviated (lucky for him) voyage. He caught a bad cold running around below-deck and left the Titanic at Cherbourg (where Uruchutu — had switched his ticket at the last minute, when he found he could sail for New York sooner on the Titanic than on the France, as he originally intended… alas for a good story, I don’t think he had Father Brown’s old berth).

In the photo Father Browne took of engineering crewmen on a lifeboat drill, the fourth man from the right looks more like an American Indian than English or Irish and appears to be in his late 20s or early 30s… Antonio was 34 when the ship went down. Is this an unknown Mexican hero?

¿Quién sabe?

Rebranding saints

Ten years after his canonization, Saint Juan Diego — the visionary of Tepayac and patron of the indigenous — has not been adopted as one of more popular saints in Mexico, nor has he been recognized by the indigenous community as “their saint”, because his “official” image is not that of an indigenous Mexican, but of a Spaniard.

Diego Monroy, presently rector of the Shrine of St. Juan Diego and former rector Basilica of Guadalupe, said the saint’s “official” portrait, by eighteenth century painter Miguel Cabrera has not impressed the Indians.

Elio Masferrer, a researcher at the National School of Anthropology and History (INAH), said that the Vatican-selected “official” Cabrera image is the problem: “Just look at his nose and his beard. That is not an ‘noble Indian’ .

Although the Milenio article from which I translated this is focused on the lack of support for the Juan Diego shrine (which might have something to do with Rev. Monroy’s track record of cost overruns and financial irregularities at the Basilica), the relative indifference to Juan Diego among the faithful may be more than a matter of an 18th century make-over.

Of course, there was some “Euro-centricism” involved in picking the “official” image of Juan Diego, and There probably is some justification to Elio Masferrer’s observation. The historical Juan Diego Cuauhtlatoatzin was an Otomí. Miguel Cabrara, a native of Oaxaca, certainly knew what indigenous people looked like (among other things, he was a master of the popular “casta” genre — portraits illustrating the then-prevailing racial categories of Mexican people) and Otomí men — even after five centuries of intermarriage with outsiders — don’t look anything close to the official image of Juan Diego.

But to point that out is to presume that “the Indians” can only identify with people that look like themselves. The Vatican had good intentions in tying Juan Diego’s canonization to the Church’s mission in serving Indigenous communities, but to presume that “authenticity” in portraiture is the way to go about this (or, more cynically, that the Cabrera image was a poor marketing decision) is to presume “Indians” are somehow completely different in their human reactions than other people.

But, I don’t think it’s ethnic identification that is at issue here. It’s something of a mystery why the Mexicans “adopt” certain official saintly images as “their” saints and reject others. Or of any particular saint. Saint George (the dragon-slaying one) somehow ended up as the patron saint of Georgia (hence the name) and England and a bunch of other places with no real ethnic or cultural connection to the fourth or fifth century Cappadocian soldier. It was the dragon that caught the fancy of early Mexican converts from religions in which snakes had spiritual significance, and Saint George’s popularity may have nothing to do with him personally, although saints on horseback do have some appeal. Saint Martin of Tours — San Martin Caballero — based on his iconic presence showing him giving a cloak (or, rather, half a cloak) to a beggar has been re-interpreted in Mexican popular belief, making him:

… especially popular among shop-keepers, who rely on the kindness of passing strangers for their livelihood, and among truck drivers, who see in his horsemanship a parallel to their own manner of earning a living. Because the horse he rides is associated with the lucky horseshoe, he is also a favourite saint among gamblers.

… especially popular among shop-keepers, who rely on the kindness of passing strangers for their livelihood, and among truck drivers, who see in his horsemanship a parallel to their own manner of earning a living. Because the horse he rides is associated with the lucky horseshoe, he is also a favourite saint among gamblers.

(Of course, maybe Saint Martin’s interest in gamblers is because he only lost half his shirt).

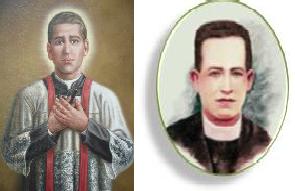

Neither Martin nor George — nor Judeo Tadeo (Saint Jude), nor Saint Michael the Archangel — all of whom are unavoidable in Mexico have a particularly Mexican look in their popular iconography. The only one who does among the saints who’ve caught the popular imagination is Toribio Romo, who after all was a Mexican.

Never mind that there is an official saint of immigration to the United States (Francis Cabrini) and another Cristero saint, Pedro Maldonado Lucero who worked as a day laborer for a time in the United States (he was a seminarian in El Paso), the holy go-to guy for migrants to the United States is Toribio Romo. Although the Catholic Church would have him a symbol of devotion to the Eucharist, in the popular imagination he is a “spirit guide” for border crossers. I’ve said I think Saint Toribio was selected for the simple reason that he came from Los Altos, Jalisco (a font of both particularly devout Catholicism AND emigrants to the United States) and he was a regular featured, good looking fellow.

Good looks may not get you to heaven, but the popular saints are celestial celebrities. And, just like terrestrial celebrities, we expect them to be attractive in ways that have nothing much to do with whatever it is that they do. That the English singer Susan Boyle was so celebrated a few years back was something of an anomoly… that an unattractive woman could sing marvelously was seen as something of a … to use a religious term… miracle. The very rarity  of her celebrity underlies the point. Princess Diana was a rather pretty young lady until she became a celebrity, when she became an international beauty. Her looks didn’t change, just the perception of her popularity. Fictional celebrities — think Batman or Spiderman aren’t played by unattractive actors — and even santones — the unofficial saints — like the mythical Jesus Malverde — are given a retroactive makeover.

of her celebrity underlies the point. Princess Diana was a rather pretty young lady until she became a celebrity, when she became an international beauty. Her looks didn’t change, just the perception of her popularity. Fictional celebrities — think Batman or Spiderman aren’t played by unattractive actors — and even santones — the unofficial saints — like the mythical Jesus Malverde — are given a retroactive makeover.

And, when it comes to the Virgin of Guadalupe, that Juan Diego was the intermediary in bringing her to the attention of the official church is less important in the popular imagination than the idea that Virgin answers all requests personally. Juan Diego — whether presented in the guise of a Spaniard or an Otomí — really isn’t all that necessary to the devout — or to the Mexicans who find the Virign herself, all the celestial celebrity they need. When the Mother of God is Mexican, one already knows what her favored sons look like… they look like everybody and anybody. And unless they’re very good looking indeed, no need for a pinup.

Clueless

I really, really try to keep U.S. politics out of this website, since this is a site talking about Mexico and Latin America, and when it comes to relations between the U.S. and this part of the planet, there’s not all that much difference between the two presumptive candidates. Still, whether we like it or not, we are going to have to deal with whoever wins the election, and how they view the rest of the world does matter.

After trying to sell the idea that the difference between Israeli and Palestinian per capita GDP was rooted in cultural values (which is why, I suppose, Qatar has the world’s highest per captial GDP, and three Muslim countries are in the top ten)…

After trying to sell the idea that the difference between Israeli and Palestinian per capita GDP was rooted in cultural values (which is why, I suppose, Qatar has the world’s highest per captial GDP, and three Muslim countries are in the top ten)…

Romney also cited differences in the U.S. and Mexican economies as proof that some cultures facilitate vibrant economies, while others impede it.

…

“The Mexico that Romney seemed to describe no longer exists,” Negroponte said. “It hasn’t for 20 years.”

The Romney campaign declined to answer specific questions about Romney’s U.S.-Mexico comparison, referring The Huffington Post to Romney’s Tuesday op-ed.

Mexican trade with the U.S. supports 6 million U.S. jobs, said Kristian Ramos, policy director of the left-leaning think tank NDN’s 21st Century Border Initiative.

Mexico ranks third among U.S. trading partners in terms of spending, and pumped $80 billion into Texas last year, Ramos said. Some analysts anticipate that Mexican economic growth will outpace that of the U.S. this year.

“The question I would ask Bettina Inclán is if Mitt Romney thinks there is something culturally wrong with Mexico that doesn’t allow its economy to grow,” said Ramos. Inclán is the Republican National Committee director of Hispanic outreach. She did not respond to a request for comment Wednesday.

Romney’s comments call into question two critical selling points for his campaign, said Ramos: Business acumen and character.

(Janell Ross — who apparently is a real paid writer for Huffington Post)

Who was that masked man?

Yes, that is indeed a guy in a lucha libre outfit in a convenience store and an ostrich. And, of course this happened in Mexico City… you know, the place Salvador Dali once said was too surreal for him.

No one seems to know why, but the luchador (and ostrich) ran amok in a unnamed Mexico City convenience store, but the owners are reluctant to press charges, fearing the big guy (whether human or avian isn’t clear) might come back to do some real damage.

Politics is rough and all is well

Interesting:

Despite dire predictions that challenging the legitimacy of the Peña Nieto electoral advantage in the First of July balloting would create chaos in the country…

Alberto Espinoza, president of the Employers’ Confederation of the Mexican Republic (Coparmex) — the national Chamber of Commerce — said that despite the challenges submitted to the presidential election, there is no evidence that this legal battle is generating political or social instability, and macroeconomic indicators are progressing smoothly.

Interviewed at the close of the 27th annual Federal District COPARMEX Assembly, Espinoza said, “There has been no change in public life … we have socia social and political stability and do not see any risk, or threat, or possibility of instability being generated in this country.”

(Jornada, my translation)

The business establishment isn’t worried about the prospects of annulling the elections. I don’t see why they should be. It’s not that the elections can’t be, or won’t be annulled, but that not going through with the process might be more destabilizing that playing by the rules.

BTW, despite all the hoo-haw about Mexico collapsing or being a failed state or on the verge of whatever disaster we’re supposed to be on the verge of this month:

Mexico’s gross domestic product (GDP) grew at an annual rate of 4 percent in the second quarter, the Mexican government said in a preliminary estimate.

Inflation came in at an annualized rate of 4.34 percent in June, representing an increase of 0.61 percent with respect to the 3.73 percent rate registered at the end of the previous quarter, the Finance and Public Credit Secretariat said in a report.

“During the second quarter of 2012, the Mexican economy continued in the expansion process, according to the results of the principal macroeconomic indicators. The growth rate moderated slightly, but it remained positive and elevated,” the secretariat said.

¡Gore Vidal presente! (3 Oct. 1925 – 31 July 2012)

Rolling back through Gore Vidal’s remarkable life — the great and terrible old man raging against the Empire; the witty, mischievous purveyor of gossip about the safely dead: the rare intellectual in Hollywood; the inconveniently related Washington insider (thanks to his much-married parent’s various partners and paramours — and his own paramours — he knew or was related to everyone from Amelia Earhart to Hollywood stars to European intellectuals and political cranks and half the Democratic Party establishment of the 50s and 60s — John Kennedy was married to his half-sister Jacqueline Bouvier and even Jimmy Carter was a distant cousin); the Army brat (his father was a West Point instructor, and he was born in the Cadet Hospital); the prematurely wise veteran of his two early novels (Williwaw, written while the 19-year old Vidal was stationed in the Aleutians as an Army private, and In a Yellow Wood, about a young veteran’s conflict between an unconventional life with the possibility of love and social and economic stability); the sexual radical whose 1948 The City and the Pillar was particularly shocking in that the gay hero’s conflict is resolved by accepting his homosexuality, and — moreover — his being a healthy, well-conflicted American male.

As part of his journey as a healthy, well-conflicted American gay man in search of self-acceptance The City and the Pillar‘s fictional protagonist, Jim Willard, travels to the Yucatán in a vain attempt to find satisfaction with a woman… Unsuccessful in finding “normalcy” as it is was socially defined in the late 1940s, Jim returns home, coming to self-acceptance, contradictions and all. The author, whose editor flat out told him “You will never be forgiven for this book” found his own literary acceptance, and contradictory voice, though his own sojourn into Guatemala.

To pay the bills, Vidal churned out a few detective novels under a pseudonym, and an odd quasi-fantasy novel (there are vampires and werewolves in it) about Richard the Lionhearted and Blondel… justifying gay relationships through history, and also marking Vidal’s debut as a historical novelist. More importantly, he developed the story, and wrote Dark Green, Bright Red … his short Central American novel, that so nicely debuts the multi-faceted Vidal — the ironic observer of human frailty that acts out of sight to influence public events, the delighted voyeur, the veteran, the name-dropper, and the voice in the wilderness decrying American imperialism and corporate chicanery.

Set in an unnamed Central American republic, Peter Nelson has come to work in the country under a cloud:

As far as he knew, the General had been told nothing of his court-martial and discharge from the American Army. José knew, of course, and he had chosen to ignore everything except their friendship when, two weeks earlier in New York, he had invited Peter to join the army of the revolution. Peter had agreed. It was not as if he had a future.

Though we don’t ask, and Vidal doesn’t tell exactly why Peter was court-martialed his reasons for going to Central America may not be all that different than Jim Willard’s were. There is a more than a hint of sexual attraction between Peter and José, even if we accept that Peter’s attraction toJosé’s sister, Elena, is more than a desperate stab at “normalcy”. When José dies in a accident, Peter beds Elena, but leave her.. which reads to me more like an attempt to assuage his own grief — an “anger fuck” to use the vernacular — than any particular feeling for the rather flighty daughter of the former (and would be future) dictator.

When the book was reviewed by the New York Times in October 1950, Donald Barr dismissed it as “a sound enough melodrama about revolution in a Central American country…” missing what the novel is — a personal tragedy (Peter’s) set inside a dark comedy, wrapped in acid political commentary about United States interference in Latin America.

General Alvarez is a standard issue Central American dictator — a Ladino in a country described as “80 percent Indian” of no particular political persuasion. He sees his recent and relatively comfortable exile in New Orleans as simply an interruption in his career — much as a gangster might view a prison sentence.

The General’s political adviser (and court jester) is another near stereotype. The French exile, De Cluny is a novelist like Vidal somewhat grudgingly admitted to the corridors of power. But, De Cluny is a third-rate hack, and the corridors of Tenango (second city of the unnamed Republic) are not those in which Vidal could stroll renewing family ties.

Who De Cluny really serves — the General, the reactionary priests threatened by the ruling Opina party’s mild reforms, Mr. Green of the World Banana Company, himself, or some unnamed others, is never clear. It may not even be clear to the cynical De Cluny himself. That the ruling Opina regime is secular and liberal (although looking to check the power of Mr. Green’s banana empire) — and popular — means the General needs to have some better rationale for overthrowing it than just “life was better with me around”. It is De Cluny, the third-rate Metternich, who comes up with “Christian Socialism” — basically neo-liberalism (in the 1940s yet!) with an overlay of paternalism (and, of course, reliance on banana exports) which wins over… some of the most devastatingly drawn stereotypical gringos abroad to be found in expat writings anywhere. And, a few professional soldiers on the make, and the more reactionary churchmen… and — we think — the World Banana Company.

The revolution is a disaster, and ends in a bloodbath. The only winner… as expected… is the World Banana Company. Peter gets out, because he can. One would like to think that, like Jim Willard, his stint in Latin America has forced him to accept who and what he is… but, in an enigmatic tale like this, we are never sure that Peter has learned anything at all.

Peter — even with his court-martial and self-imposed exile — is the quintessential American military man loose in Latin America. It is not true that “there is no evil in this book, only adventure-tale villainy” as Donald Barr wrote about the then new novel. Four years later, Jacobo Arbenz — the Guatemalan President whose elected government instituted some mild social reforms and challenged the power of both the Roman Catholic Church and the United Fruit Company was overthrown by a military uprising of no particular political persuasion (other than turning back the clock on the reforms) and largely the handiwork of then shadowy foreigners being manipulated by the CIA. That the coup’s ostensible leader was coming in from Honduras aside, Dark Green, Bright Red was more in the nature of a prophesy than a “adventure-tale”.

Perhaps it is only in hindsight — more than 60 years after it’s 1950 publication — that we can see that Dark Green, Bright Red shows us why we will miss Gore Vidal — cantankerous and tiresome as he sometimes was in his old age, he was a shrewd political analyst. Satire, as a literary form, is intended to convey moral values, and Vidal was a moralist in both the sense of giving us a parable with a moral and in the sense of standing in opposition to immorality. That our  flawed human nature prevents us from seeing the wrongness in our actions are tragic. That power corrupts is no secret. That we are willing to be corrupted (even if through innocence, like Elena, or a lack of self-awareness and acceptance like Peter and José) is tragedy. That we will be thwarted is the moral of that lesson. That political and social culture can be corrupted and perverted for the benefit of outsiders, and that the outsiders avoid any responsibility for their actions is a moral outrage.

flawed human nature prevents us from seeing the wrongness in our actions are tragic. That power corrupts is no secret. That we are willing to be corrupted (even if through innocence, like Elena, or a lack of self-awareness and acceptance like Peter and José) is tragedy. That we will be thwarted is the moral of that lesson. That political and social culture can be corrupted and perverted for the benefit of outsiders, and that the outsiders avoid any responsibility for their actions is a moral outrage.

That we failed to heed Vidal’s warnings, mistaking elegance for decadence, prophesy for wit, and incessant intellectual curiosity for a disorderly life is our tragedy. That Latin America has so often paid for our failure of imagination is, to those of us here, reason enough to mourn Gore Vidal’s passing.

No smoking gun… yet (Monex and money laundering)

Even before Andres Manuel Lopez Obradór raised the possibility of installing an “interim” president who would only serve until new presidential elections could be called, I had pointed out that such a scenario was not only possible, but had constitutional validity and there are precedents for doing so.

The most damning charge that has been raised and which would make annulling the election a reasonable alternative are various charges that the PRI financed its campaign with laundered money. What started as accusations of vote buying though distribution of MONEX debit cards has exploded into a much larger scandal with the accusations by U.S. businessman, José Luis Ponce de Aquino that his Frontera Television Network (which broadcasts in both the United States and Mexico) was paid for PRI advertising to be paid indirectly by MONEX. On June 14, Ponce de Aquino filed suit against the Peña Nieto campaign for 56 million dollars in unpaid advertising bills. The PRD jumped on the case, raising complaints about the triangulation of funds through the MONEX-PRI-FTN connection. Althoughy the PRI, the Peña Nieto campaign and the candidate himself initially denied any connection to MONEX, they have had to backtrack, and admit that at least twenty agreements between the bank and the campaign were in existence. (Source: Sin Embargo)

The Elections Tribunal does not seem to be searching for a “smoking gun” to allow them to annul the election — on the contrary, they appear to be doing everything possible to legitimize the June 1 results. But this makes it all that much harder for them to do so, and if they do confirm the Peña Nieto victory, it will be even more difficult to convince an very large sector of the Mexican population that the elections were democratic, fair or “free, genuine and credible.“

The good witch-doctor

María de la Luz Matuz began her career (or is it “found her calling”?) at the age of seven. That was in 1922. With her death earlier today (Monday), at the age of 97, what was surely the longest medical practice in the world ended.

Matuz was a traditional curandera, whose backyard clinica in Vicam, Sonora became something of the Mayo Clinic of witch-doctoring, attracting patients from throughout the America, Europe and Asia. Considering how much we attribute a curandera’s skills to psychology, the fact that Matuz spoke only Yaquí (although she understood Spanish), her remarkable skill in diagnosing illnesses and successfully alleviating, and often curing, physical and psychological illnesses is hard to explain.

Matuz was a traditional curandera, whose backyard clinica in Vicam, Sonora became something of the Mayo Clinic of witch-doctoring, attracting patients from throughout the America, Europe and Asia. Considering how much we attribute a curandera’s skills to psychology, the fact that Matuz spoke only Yaquí (although she understood Spanish), her remarkable skill in diagnosing illnesses and successfully alleviating, and often curing, physical and psychological illnesses is hard to explain.

The only complaints ever made about her practice were not directed at her, but at people in nearby Ciudad Obregon, who claimed to be her relations and have been taught her skills… and who charged handsomely for what were said to be remedies personally concocted by María Matuz. Most of her patients left “donations” more in the range of a visit to a Dr. Simi clinic… ten or twenty or fifty pesos… and that included her home-brewed prescriptions. She was not in competition with the medical profession, taking referrals from them (especially psychologists, who respected her special gifts) and had been under medical care since breaking her hip after a recent fall.

How much of her skill was due to faith healing, how much to some inborn diagnostic sense and how much to a genuine understanding of herbal remedies, is probably a fruitless area of speculation. Whatever it was she was doing, she did it well, and did some good for a lot of people, for a very long time… and that was more than enough.

You go Uruguay and I’ll go my aguay…

A career technocrat with the long, wispy hair of an aging rocker, [Uruguayan National Committee on Drugs Secretary-General Julio Calzada] said he had been busy calculating how much marijuana Uruguay must grow to put illegal dealers out of business. He has concluded that with about 70,000 monthly users, the haul must be at least 5,000 pounds a month.

“We have to guarantee that all of our users are going to be able to get a quality product,” he said.

The only real danger I can see in the Uruguayan plan to create a government-run marijuana distribution system is that they’re gonna need some kind of marijuana quality control officers. Like these guys: