Never mind!

It looks now as if Mexico City will not become Mexico City. That is, while the Senate voted to allow for constitutional changes that would give the Federal District autonomy in its elections and budget, the Chamber of Deputies killed the bill, probably out of concern by the PRI and PVEM (the fake “Green” Party) that neither would win any elections here every again. Not that they do now.

Politics, the Mexican way…

Wannabe independent candidate for the Federal Chamber of Delegates Rafaela Romo Orozco was denied a place on the ballot for refusing to file her campaign expenditures report with the National Elections Institute (INE). I guess that makes her like Jesus, right?

(Emeequis)

Say goodbye to “Distrito Federal”…

… and hello to “Ciudad de México” … whatever the name, like Maldita Vencindad called it “un grande circo”:

In Baltimore, it was the spinal fracture that broke the camel’s back. Here, the people have endured much more:

Yesterday, as Baltimore restaged the intifada, protesters in Mexico, in Chilpancingo, the capital of the state of Guerrero, rammed a flaming truck into the glass-fronted congressional building, and set fire to at least six other vehicles. They had taken to the streets to mark the seven-month anniversary of the disappearances of the 43 students, who have come to represent the hundreds of thousands of dead as a result of US-Mexico’s drug, immigration, and trade policies (a number of the relatives of the disappeared are currently in New York, where they are appealing to the United Nations to end Washington’s so-called Merida Initiative, or Plan Mexico, which sends billions of dollars to Mexico to supposedly fight drugs but which the relatives of the 43 say goes to “suppress dissent”). [Greg Grandin in The Nation, 28 April 2015]

It should have been perfectly obvious, though in the US (and here) it’s only when it happens to some other repressive society:

… while no one condones looting, on the other hand one can understand the pent-up feelings that may result from decades of repression and people who’ve had members of their family killed by that regime, for them to be taking their feelings out on that regime

[Donald Rumsfeld, justifying looting in Bagdad, 4/11/2003]

Tlatelolco’s mole-men headed for Nepal

25 members of the Brigada de Rescate Topos Tlatelolco…the “mole-men” of Mexico … are on their way to Kathmandu. As always, these volunteers who… in the spirit of those skinny teenagers, construction workers, bureaucrats, doctors, housewives, office workers and others who risked their own lives after the 17 September 1985 earthquake tht brought down high-rises in their own neighborhood to find survivors and recover the dead… are willing to go at a moments notice, to the assistance of victims of natural disasters anywhere in the world.

The Topos are probably the most respected (and experienced) outfit of this kind in the world.

You know the drill: donations in any currency, via paypal: Brigada de Rescate Topos Tlatelolco

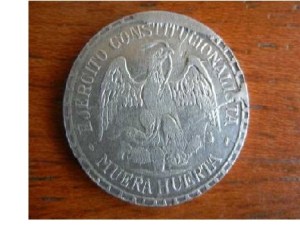

The wages of revolution are… 75 centavos a day

Bet you didn’t know this. The first minimum wage laws in the Americas was not the 1938 Fair Labor Standards Act signed by Franklin D. Roosevelt. It was the Decreto sobre aumento de salarios signed by Venustiano Carranza on 26 April 1915, setting a minimum wage of 0.75 pesos a day, and forbidding employers from adding extra hours to the workday (on farms it was sunup to sundown).

This wasn’t totally done out the goodness of Carranza’s heart. At the time, the Constitutional Republic could only enforce the wage in the states controlled by Álvaro Obregón (Michoacán, Querétaro, Hidalgo y Guanajuato). Pushing Carranza to i ssue his executive order, Obregón had a dual purpose. Coming in the immediate aftermath of the Battle of Celaya (6-15 April), which crushed Pancho Villa’s army as a military force, Carranza (and Obregón) there was widespread opposition to the Constitutionalists among the populace, and Obregón — always known for his preference for buying off his opponents as an alternative to crushing them militarily — saw potential allies in the working class. And, remember that the Mexican economy had collapsed. With no real central government, or rather, with several competing governments, states and municipalities, as well as various revolutionary

ssue his executive order, Obregón had a dual purpose. Coming in the immediate aftermath of the Battle of Celaya (6-15 April), which crushed Pancho Villa’s army as a military force, Carranza (and Obregón) there was widespread opposition to the Constitutionalists among the populace, and Obregón — always known for his preference for buying off his opponents as an alternative to crushing them militarily — saw potential allies in the working class. And, remember that the Mexican economy had collapsed. With no real central government, or rather, with several competing governments, states and municipalities, as well as various revolutionary

factions, had all issued their own money, which might or might not be considered real depending not just on whatever faction was in control in any given area, but how merchants and bankers valued the currency. While paying in Constitutionalist pesos in Constitutionalist areas would immediately make it the de facto, as well as legal tender, in those states, it also meant that the merchants knew that the currency was being regularly paid out, and could be counted on to hold its value, even if it circulated in regions outside Constituionalist control assuming it would eventually find its way into Constitutionalist territory . Given that they were winning, those 75 centavos a day, were doing as much to increase that territory as Obregón’s army was.

This sucks!

A U.S. Border Patrol agent who killed a teenager when he fired across the border from Texas into Mexico cannot be sued in U.S. courts by the Mexican teen’s family, a federal appeals court ruled Friday.

The unanimous ruling was issued by the full 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, reversing most of an earlier 2-1 ruling by a three-judge panel of the court. The border agent’s lawyer said the opinion vindicated his client.

An attorney for the teen’s family said they haven’t decided whether to appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court.

[…]

U.S. Border Patrol agent Jesus Mesa Jr. shot 15-year-old Sergio Adrian Hernandez Guereca in June 2010. U.S. investigators said Mesa was trying to arrest immigrants who had illegally crossed into the country when he was attacked by people throwing rocks. Mesa fired his weapon across the Rio Grande, twice hitting Hernandez Guereca.

The shooting occurred near a bridge between El Paso, Texas, and Ciudad Juarez, Chihuahua

Originally the family’s lawsuit was filed in U.S. District Court, where a judge ruled that they couldn’t sue in the U.S. because the shooting’s effects were “felt in Mexico.” The three-judge panel of the 5th Circuit later held that Mesa could be sued, but Friday’s decision by the full court overturned that finding and upheld the district judge.

The full court rejected the family’s contention that Mesa’s immunity from a civil suit was overcome by the U.S. Constitution’s Fourth Amendment, which guarantees the right of “the people to be secure in their persons,” or by Fifth Amendment protections against deprivation of life without due process of law.

I understand the legal reasoning, but it still sucks. The United States claims “universal jurisdiction” for crimes outside its own borders, but at the same time rejects the authority of international criminal courts to try its own citizens. I don’t see how Officer Mesa will ever face justice, but the Hernandez family deserves some. Short of calling the incident an act of war, it was an aggression against a sovereign nation by an armed agent of a foreign government. At a minimum, the Republic is owed a formal apology (I’d settle for the U.S. Ambassador abjectly handing over a hand-written apology by Barack Obama to Enrique Peña Neito… and Sergio Adrian Hernandez Guereca’s mother) AND the Hernandez family is owed a large cash settlement. AND… Officer Mesa should never be anywhere near the Juarez again.

A good idea whose time might come

Although it was shot down (for now, anyway) an interesting political reform that might pave the way to a post-party democracy has surfaced here. Basically under the excuse that its too close to the elections now to reform our legislative system, representatives from the 20 million indigenous Mexicans in 28 states have proposed that the indigenous communities could elect representatives to a sixth “conscription”.

Mexico’s electoral system was designed to prevent any one political PARTY from gaining complete control. It’s a complicated process, but in addition to the representatives elected by district or state, there are an addition batch of legislators chosen by the parties based on their relative vote within the five “conscriptions”… a multi-state regional area… based on complicated formulas that preclude any one party from having more than 2/3rds of the seats in any one house. Meant to assure that minority parties are guaranteed at least a seat in the legislature, the system has been endlessly tweaked, mostly to guarantee the hegemony of the three major parties, PRI, PAN and also-ran PRD.

Mexico’s electoral system was designed to prevent any one political PARTY from gaining complete control. It’s a complicated process, but in addition to the representatives elected by district or state, there are an addition batch of legislators chosen by the parties based on their relative vote within the five “conscriptions”… a multi-state regional area… based on complicated formulas that preclude any one party from having more than 2/3rds of the seats in any one house. Meant to assure that minority parties are guaranteed at least a seat in the legislature, the system has been endlessly tweaked, mostly to guarantee the hegemony of the three major parties, PRI, PAN and also-ran PRD.

This serves the party interests very well, if not guaranteeing some politicians a seat in the legislature, at least guaranteeing they will be candidates for one office or another. But does it serve the interests of their constituents?

I’m not convinced that living in the same general geographical area has much to do with whether a representative can speak for my interests (what does a yuppie in Guadalajara have in common with a Mixtec farmer, other than perhaps both living in the State of Jalisco?). Though we’re stuck with administration by geographical proximity, I’ve wondered whether representation by geographical proximity is even necessary. Maybe in the 18th century, it seemed like a good idea, just to make it easier to count ballots, there is no technical reason voting MUST be this way. One could vote, by say, economic or social interest.

Which makes the idea floated by the indigenous representatives so intriguing. Having common interests, but spread over 28 states (at least this group), they see common interests less tied to geography (where indigenous communities are often outnumbered by their neighbors) than ethnicity… or, in this instance, by the recognition in the Constitution of their right to adhere to “usos y costumbres”. That is, although separated by political boundaries within the country, they share enough common values to justify representation in a body supposedly representing the people as a whole.

I’m not sure ethnicity is the best way to select representatives (perhaps by “social sector”… labor, business, education, agriculture… or whatever fits the country’s population the best), and I don’t think we’ll ever completely dispense with the need for geographical representatives or with political parties, but extending proportional voting to meet the shared interests of larger constituencies sounds perfectly rational… and perfectly “do-able” to me — the technology certainly exists to control ballot access to voters within any given constituency now no matter where the voter is in the country (Mexico pioneered the software for the gold standard of voter identification procedures) and counting ballots over the whole country to determine seats in a legislature isn’t any more complex than counting national ballots as far as the computers are concerned.

With the idea of a new Constitution having been floated by both the left and by the Catholic Church, and the low regard for political parties (especially the traditional big three) right now, perhaps Mexico could rethink the political process, creating something new, and something suitable for the 21st century.

Georgina Saldierna, Indígenas exigen elegir a sus legisladores sin partidos, Jornada, 24 April 2015, page 10.

Our “show me the Green” party.

When Josefina M. was cold-called by the Green Party of Mexico (PVEM), she politely responded to their telephone survey, answering questions on crime, education, jobs and other issues.

She was careful not to give out her address or any other personal details, nor agree to further correspondence. A few days later, however, she was surprised to find an envelope hand-delivered to her Guadalajara home stamped with the tag, “For Green Party Affiliates.” Inside, she found a gift card in her name, containing the Green Party logo, along with a letter explaining how she could use it to obtain discounts in a variety of stores such as Sears, Chedraui and Farmacia del Ahorro.

The card is one of thousands distributed by the Green Party in the run up to the June 7 local and legislative elections, which will bring in 500 new federal deputies, nine governors, new state legislatures and 900…

900…

View original post 886 more words

Don’t get around much any more…

My posting is going to be irregular for the next few weeks (maybe the next few months). I’ve been revising “Gods, Gachupines and Gringos” and… with so little sleeping and so much reading… on top of trying to get to press several books for Montezuma Books, I’m not completely out of my mind, though I’m working on that, too.

What’s going on? Mexico’s military build-up

Much was made this last weekend over the 100s of U.S. military vehicles crossing into Mexico, with this video (from El Mañana of Nuevo Laredo) raising two unanswerable questions: why is there a military build-up?, and why is Mexico getting military equipment from the only country that could conceivably be an existential threat to the nation’s existence?

Although Mexico is the 11st most populous nation on the planet, and the 10th largest economy, with no foreign commitments, only once having fought outside its own territory, and its very few foreign excursions being well-executed rescue and relief operations (including New Orleans, after Hurricane Katrina, where the Mexican Army showed up before the Louisiana National Guard!), and the only foreign threats being more theoretical than anything else (other than the United States, which prefers a “stable” Mexico, even if it means subversion, the only possible national security threats from the outside would be the collapse of a neighboring country, and a possible refugee crisis, or a spill-over from a civil war in Guatemala) Mexico has never needed a large military force.

According to Global Firepower, Mexico is ranked the 31st on the list of military powers… between #30 Switzerland, and #32, South Africa… two countries not likely to be launching offensive wars any time soon. Nor is Mexico. Brazil, which does have a history of expansionist ambitions (though not in the last century or so) and a major arms industry comes in at #22… but…

World-wide, military spending is down 4 percent, with the Latin American nations showing the largest decreases. Venezuela’s military budget is down by 34% and even Brazil managed to cut the budget by 1.7 percent. The exceptions are Paraguay (up 13%) and Mexico (up 11%).

Given that there has been a problem with banditry and gangsterism packaged as something new and more threatening under the names of “cartels” or the ridiculous “TCOs” (Trans-national Criminal Organizations… or what used to be called “smugglers”), there might seem to be a rationale for the build-up. However, the government itself is claiming that crime has fallen, and the “Institute for Economics and Peace” claims that the country is more peaceful.

It may well be, as is argued, especially in the media, that crime is NOT dropping, and that it is simply not being talked about, but more and more, there has been a realization that the military is the wrong tool to use in the fight against those so-called “cartels”, and as a substitute for normal police.

So why… in a country which had always been proud of its successfully de-militarizing its government, and had kept military spending a modest 6% of the national budget for decades (even during the Calderón “War on Drugs”) suddenly spending more?

Regeneración, overtly “leftist” even for Mexico, makes a good case that the Mexican military build-up has less to do with the needs of Mexico than it does with U.S. “geo-strategic interests”. Mesfiles has always said that the “Plan Mérida” money provided by the United States, ostensibly to fight the “cartels” was always meant to both legitimize the Calderón Administration and to prop up the US industries that provide military and “people control” equipment and services than anything else. But, Regeneración argues that with the neo-liberal “reforms” going back to the 1980s, making Mexico more and more an economic satellite of the United States, there is the assumption now that Mexico could (and should) serve as a military adjunct to U.S. forces.

While it is troubling enough that those of us who have lived in areas supposed requiring a military backup (or replacement) of police (like Mazatlán, where I lived for several years) became inured to the sight of soldiers and sailors in the streets (and a soldier with a 50-cal rifle pointed at you while sitting in traffic) and some eye-brow raising speeches by generals hinting that their loyalty was to the President, and not the nation, I don’t see us become a militarized state. After all, the country’s military heroes have been mostly amateurs (Morelos, the priest; Villa, the — uh— cattleman; Obergon, the farmer and businessman; Rafael Buelna, the law student) and our greatest modern Secretary of War, Joaquín Amaro, was probably the only bureaucrat in history who spent his career downsizing his department and cutting his own budget. This is a country that cut its military budget even during its own foreign war (the “War Against Nazis and Fascists”), and just doesn’t “do” militarism.

But, I do see — in small movements like allowing Mexican troops to serve in U.N. peace-keeping operations (something always avoided before), and in allowing foreign agents to carry weapons on Mexican territory — as well as the economic integration with the U.S. and Canada (another military adjunct of U.S. interests) a very troubling sign that Mexico will be dragged into outside conflicts that do not serve its own interest. And, that the military will be used to protect not our our interests, but those of the United States. With, U.S. weapons, paid for by Mexican taxpayers.