Grito de guerra

Students win one round… on to round two?

The IPN strike has ended after three and a half months. Students at the 44 academic and vocational schools that comprise the National Polytechnic Institute walked out in October, over complaints about educational “reforms” that would compromise the school’s stated mission of investigation and research that serves the Mexican nation, misuse of state funds meant for supporting students and research, ineffective administration, and attempts to stifle political speech on campus.

Unlike other major universities in Mexico, IPN’s director is not appointed by the university community, but by the Secretary of Public Instruction. One of the most pressing was the replacement of then director Yoloxóchitl Bustamante Díez, who — students believed — was overly-generous with the payroll and benefits for university administrators, but, was also doing little or nothing… or even encouraging… “educational reforms” proposed by the Peña Nieto administration… that would stint, or even end, funding for academic studies, in favor of vocational education. The latter was something even those students in purely vocational training programs objected to, understanding that the school was always intended to further Mexican scientific and industrial development and that their own careers depended on the academic research and applied science research of their academic peers.

Bustamante’s forced resignation cleared away one demand, although the administration tried to find a director who could be sold to the students, while not undermining their own plans to depoliticize the students, and to de-fund pure research, they were finally forced to offer the position to Enrique Fernández Fassnacht… a well respected chemical engineer and, at the time, the Executive Director of ANUIES (The National Association of Universities and Institutes of Higher Education, for its Spanish acronym), on 20 November (Revolution Day!).

I happened to be watching the negotiations (which were being broadcast live on the school’s open access television channel) when Dr. Fernández Fassnacht — who had been sitting with the Secretary of Education’s negotiators, moved his chair to the student side of the table. Having taken the post as director, he felt obliged to defend the school, and … symbolically… was signalling that the students’ demands were not only just, but in the best interests of the university and the state. The proposed “reforms” that would have folded the country’s second largest educational institution into a national chain of “voc-tec” colleges meant to train (not educate) workers for local businesses (often foreign-run enterprises) was dead, and what remained as an original issue were the questions of political speech and campus security.

Because it is not, as most universities in Mexico are, an “Autonomous body” (funded by the state, but self-regulating), IPN is still subject to direct interference by the state and Federal District governments. Withdrawing Mexico City Police and replacing them (as in the autonomous universities) with University controlled security forces, is not something that will happen overnight, but is meant both to meet the demand for better security on campus, and to remove a force that has been used to stamp out dissent on campus. Promises of non-interference in student politics have been agreed to by the Secretary of Education, the Secretariat of Governance (Interior Ministry, or Home Secretary), and — with the approval of the 44 campus representative bodies — a rollback in the academic schedule to allow for students to make up the time lost to the strike — the students have achieved a complete victory.

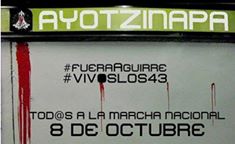

And, now, with the 160,000 or so students not having focus on their own issues, they can join with the nation’s other students, workers, campesinos and middle class … Ayotzinapa.

But… for tonight. IPN is a “technical school”, and music is a technical skill, so of course the school has a fine symphony. The only institute of higher learning with its own official mambo: Perez Prado’s “Mambo Politécnico” what better way to cheer the victory?

Bat crossing

La Llorona 43

I just returned from a few days at the Feria Internacional del libro de Guadalajara… one of the biggest (if not THE biggest) “intellectual” gathering in Latin America, where… of course… there were a plethora of “intellectual” responses to the forced disappearance of 43 Normal School students, and the meaning of it all. While many wise and well-chosen words were spoken, what strikes me is that the intellectuals are not the ones who give meaning to the event, but the people themselves.

And, something even the historians are missing, to give meaning to Ayotzinapa the people turn… not to the “-isms” of scholars and theorists… but to traditional sources, our myths and our music.

“La Llorona” (the weeping woman) has haunted Mexico since pre-conquest times. Perhaps, as the scholars say, she is Cihuacóatl, the Goddess of childbirth, or rather, her attendent spirits, the Cihuateteo … the ghosts of mothers who died in childbirth. She was often spotted in Tenochtitlán, weeping for her lost children, and warning of impending disaster. Later, she was identified as la Malache, the Aztec noblewoman who became Cortés’ mistress and interpreter, selling out her people (her children) for personal revenge… her spirit condemned to wander the earth, mourning her own destruction, and warning of danger. Or… Empress Carlota, the mad, bad and sad would-be mother of the Mexican people. Or, as she has for the past century and a half been seen, as a singular woman… the tossed-away mistress who murders her children, and must spend eternity warning of false hopes and false loves.

Reduced to a single figure, La Llorona is the anti-Guadalupe. Mexico’s good mother — whether she is Tonantzin, “Mother Earth” or Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe — is tolerant of all, and forgiving of all. She is the Mexico of patience and acceptance. La Llorona is Mexico frustrated and pushed to madness by deceit. Or she who warns us that madness and death will follow those who allow themselves to be deceived.

Reduced to a single figure, La Llorona is the anti-Guadalupe. Mexico’s good mother — whether she is Tonantzin, “Mother Earth” or Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe — is tolerant of all, and forgiving of all. She is the Mexico of patience and acceptance. La Llorona is Mexico frustrated and pushed to madness by deceit. Or she who warns us that madness and death will follow those who allow themselves to be deceived.

And so… it is not the well-chosen words of the doyenne of the left, Elena Pontiatowska, or media-saavy apologist for the state, Enrique Krauze, that resonates with the people. It is the song of La Llorona… a grief-stricken cry to Heaven on the one hand, and on the other, a warning to the state that the people’s frustration, and what they see as the deceptions of the state … have led to tragedy, and could easily turn to madness.

We are not all the proper type of people, less 43 of us. We are people together, from Tijuana to Chiapas… ladies and gentlemen, fighting the power… Mexico wake up!

Sources:

La Llorona (México): Mytos y leyendas

“neverland”, La verdadera leyenda de la llorona: 28 November 2008, Las cosas que nunca existieron

Angelica Galicia, La Llorona: Un Lamento de Cinco Siglos. Inside Mexico

Chavela Vargas “La Llorona” (with lyrics):

Diego Rivera and the Indian

It’s considered retro to use the word “Indian” when speaking of indigenous American people, and one asssumes that were he alive today, Rivera would speak of “indigenos” and not “indios”… unless he was talking about the central figure in his “people’s communion” panel in the murals that fill the Secretariat of Public Instruction.

The man serving the masses… or the celebrant of the ‘people’s Mass” perhaps… is Doctor Pandurang Sadashiv Khankhoje, a Brahman from Maharashtra, India, who took a very different path from that of Mahatma Gandhi in the struggle to free India from the British. I don’t so much mean that he had no time for Gandhi’s passive resistance movement (Khankoje, although a Communist, was supported by the Kaiser’s government during World War I, raising an Indian revolutionary army in Turkey, to overthrow the British… among other less than passive means), but that, unlike the Mahatma, he saw no future for India in its traditionalist agriculture. One of the first modern plant geneticists, Khankoje … like Trotsky, found refuge in Mexico where no one found anything particular ennobling in the idea of inefficient rural labor.

With “land and liberty” the driving force of revolutionary peasants not just in India, but in Mexico… and just about everywhere else in the last century… his organizing skills as a revolutionary leader, and his scientific knowledge as a geneticist, were particularly welcome. One of the founders of the rural agricultural schools (the ones our government has been trying to close, which is what recently got a bunch of students killed, and has led to the massive demonstrations in our streets), Khankoje saw freeing the masses from their back.breaking labor through the development of better corn varieties, and a better educated peasantry as the path to liberty. Radical indeed!

The first Thanksgiving (and mine)

Reposted from 22 November 2007:

My best Thanksgiving dinner was at “el Rey de Pavo” on calle Simon Bolivar (or is it Motolinía?) — a little semi-hole in the wall joint serving nothing but turkey, 7 days a week — turkey tacos, turkey tortas, turkey soup, turkey mole… With limited seating, I had thanksgiving dinner with a bunch of jolly Quechans from Ecuador who’d come up to Mexico City to sell silk scarves on the streets.

OK, so we had to watch futbol, and not football. And the half-time show was a skinny old guy with a 12-string guitar. I had jamaica, which is the closest thing to cranberry you’re going to find in Mexico (it’s at least a pretty red color, and kind of tart)… but the basics were there. A peaceable dinner of corn and turkey with a bunch of Indians.

I don’t think the custom started with our Puritan Fathers, by the way… though the Plymouth Colonists and Squanto obviously got along a tad better than the folks at America’s first “inter-racial encounter” and dinner-party

Cortés had incredible luck off Cozumel. His ships were separated, and Pedro de Alvarado had arrived first. Alvarado, who turned out to be one of the greediest of the conquistadors, was stealing turkeys from the local villages when Cortés arrived. More importantly for Cortés, his crew had found two Spaniards. They were the last survivors of a shipwreck eight years earlier—the others had been sacrificed and eaten. Gonzalo Guerrero, a sailor, had married the local chief’s daughter. He had three children (these little Guerreros are probably the first modern Mexicans, mestizos – mixed bloods – part European and part indigenous), a responsible job as an advisor to his father-in-law and no intention of becoming a common sailor again.

The other Spaniard, Gerónimo de Aguilar, was a priest and carpenter. It was his carpentry skills that kept him alive; they made him a valuable slave. Father Aguilar was more than happy to be rescued. Slavery was bad and the human sacrifice worse,1 but what terrified Father Aguilar were women. As a priest, he had taken a vow of celibacy and the indigenous people simply couldn’t comprehend a healthy young man refusing to take a wife. Eight years of temptation was enough. He considered his rescuers God-sent. He spoke fluent Mayan and was more talkative than Melchor.

Father Aguilar preached a sermon in Mayan, pouring out eight years of built-up frustration and anger. Though the people had treated their visitors kindly and fed them, the Spaniards insulted their hosts, destroyed the local temple and sailed north. Landing at the mouth of the Usumacinta river (near modern Frontera, Tabasco), they found much warier Mayans—they had evacuated their women and children and cautiously approached the Spaniards, sprinkling incense. The Spaniards thought it was a compliment, but the truth is that Europeans didn’t bathe, and the indigenous people were extremely clean. The Spaniards smelled terrible, but the Mayans were much too polite to say anything about it.2

These extremely polite people fed the Spaniards a turkey dinner and then nicely told them to go home, otherwise, regrettably, they would have to kill them. The smelly Spaniards asked to visit the Mayans’ houses. The Mayans, still polite, suggested the Spaniards had missed something in the translation. Cortés trotted out his lawyers, read the official document and turned his cannons against the Mayan stone clubs and obsidian swords. It was only a test to see if cannons, horses and war-dogs were effective weapons. The cannons scared people as much as killed them. Horses were unknown in the Americas, and the only dogs were small animals (ancestors of today’s Chihuahua) that were used both for food and for pets. Melchor, the grumpy old cross-eyed fisherman, took this as his cue to exit history.

1 When she learned of her son’s shipwreck and his probable fate, Aguilar’s mother became a vegetarian.

2Americans, north and south, generally bathe daily—one of the few indigenous customs adopted throughout the hemisphere. In Mexico City, the custom is so well ingrained that “bath houses” are just that—places to clean up when there’s no water at home. This confuses some gay visitors, for whom a “bath house” has a different purpose, though such institutions also exist.

She can lift my luggage

Getting ready to move my library, I’ve got three boxes on the floor here weighing a bit over 30 kilos each. Figuring out how I’m going to wrestle them down a flight of stairs, into the car, drive them to the shipping service, and get them in the door is an “weighty” concern. I need to get ahold of Tania Mascorro Osuna of la Reforma, Sinaloa,. SHe won a gold medal in women’s weighlifting at the Central American/Caribbean Games being held this week in Veracruz. Ms. Mascorro set a new record in the 75 and over kilo division, lifting 118 Kilos (about 260 pounds).

Ferguson… or why the U.S. is not Mexico, nor Mexico the U.S.

I was rather appalled a while back by the reaction by U.S. commentators to the news that three gangsters “confessed” to killing the 43 normalistas with the help of the local police. Things like “I hope they get the death penalty”. Uh… considering Mexico hasn’t had the death penalty since 1964, and the United States is about the only place in the Americas with one not only on the books, but often enough carried out, I suppose that can be “excused” as the usual provincial thinking. When I mentioned that such thinking was considered “barbaric” here, one gringa took me to task, “daring” me to say that to the parents of the missing (and presumably dead) students. She was rather taken aback when I said I’d be happy to, but it would be preaching to the converted. I pointed out that none of the families had mentioned any wish to see these particular guys harmed (imprisoned yes, but other than that, nothing), nor was the anger (even among the victims’ families) directed at these particular gangsters, but rather at the conditions that allowed these kinds of crimes to occur. If there is a call for vengeance, it is against not against individual trigger-men, but against those who allowed criminality to flourish for their own selfish ends.

In Ferguson, Missouri, where another murder is being protested (much more violently than here in Mexico), I notice the anger is directed NOT at the “system” that allows the abuses, but at the individual policeman who pulled the trigger. While there is a sense that “the system” is rotten, it seems that it is more important to the people in Missouri to see the individual actor punished, and only after that, to consider what lay behind the crime.

While both here and in the United States, calls by the government for “calm” (meaning for people protesting police abuse not to unduly inconvenience the police, apparently) are rather grotesque. While what violence has occurred here is blamed either (by the protesters) on agentes provacatuers or (by the government) on “anarchists”… either of which might be true, or both true, it was rather minimal, and both the state, and the dissidents, both claim to have had a common interest in preventing it. Both sides were rather apologetic for what violence occurred, and are at pains to distance themselves from it… the state doing its best to justify “regrettable” actions, and the dissidents going to great lengths to claim those who were arrested were “innocent bystanders” or random scapegoats for state violence.

In the U.S., the assumption was that there would be violence, and both sides seemed to welcome it. Those sympathizing with the protesters (myself, from afar, among them) tend to see “righteous rage” while the “law-n-order” types are almost gleeful in reading into the violence their own prejudices and preconceptions about minority people and the “left” (or what passes for the left in the U.S.). And, in the U.S. there are pro-police demonstrations, and those who support the individual police officer. Naturally here, no one is going to picket in favor of a couple of gangsters, but what open support was shown for police violence has been condemned by just about everyone on the grounds of bad taste, if nothing else.

While I’m aware that there are those who read the deeper meaning of entrenched racism into the “symbolic” crime in Missouri, and are fed up with it (and justifiably angry about it), the protests don’t seem to be going beyond this one “symbolic crime”. Here, its as if the “symbolic crime” — the disappearance of the 43 normalistas — is only the platform for a discussion (a rather noisy discussion, punctuated at times by the sound of breaking windows and illuminated with molotov cocktails) of our deeper issues, and a willingness to bring up even the theories of governance. That the systemic racism and assumptions about class in the United States is rooted in the system of governance and economic assumptions is only raised by the most “radical” of voices, and only in the most fringe of media outlets. Here, the possibility of changing the way political parties work, or the existence of political parties, the present Constitution, and the economic system itself are all fair game for the mass media.

Whether either country will see more than some tweaks in the system is doubtful, but worth noting is that while U.S. media calls this a “failed state” for not protecting its minorities, no one would say the same of the United States, although in both countries, there is a obvious failure to meet the needs of its citizens. That in the U.S., the anger is channeled into minor reforms (and the need for “punishment”) probably means less — not more — meaningful tweaks than we are likely to see here, where one may not enjoy the vicarious thrill of seeing the guilty punished, the groundwork for imperfect change has been laid.

Not just drugs

I am heartily sick of the meme that the U.S. end of the so-called “drug war” is the entire cause of violence here… drugs may be part of the U.S. caused problems, but only one part. in Al Jazeera:

Beefed up state security extends beyond counter-narcotics efforts, and includes economic objectives that journalist Dawn Paley has dubbed “drug war capitalism.” The incentives include assuring foreign investors of the safety of their investments, supporting privatization, and enriching military contractors and arms manufacturers. Militarized security also facilitates the political repression of groups resisting historical exploitation and neoliberal policies, including activists, trade unions, teachers, and indigenous and campesino communities fighting dispossession, such as those in the impoverished state of Guerrero that is home to the Ayotzinapa teachers’ school. In fact, reports suggest that the vanished students may have been targeted in part because of their poor, rural left-wing school’s activism against regressive educational reforms.

Mexico’s war on drugs also plays out against the backdrop of U.S. trade policy. For example, the North American Free Trade Agreement has had a devastating effect on the country: Depressing wages, displacing small farmers, increasing migration to the U.S. and exacerbating poverty, which in turn fuels continued activism against the government.

What child is this?

One of the best known Mexican photographers of the late Porfiriate and Revolutionary era took this photo of his daughter about 1910. His great-great grandson, is a well-known contemporary Mexican photographer. That he bears the same name as the turn of the last century photographer often is overshadowed by having the same family name as the girl in the photo, his great-aunt, Frida.