Interamerican idol

How do the Venezuelans get the leaders of the Americas to follow their tune?

Sure they have a Prez who can give some rousing speeches, and some weapons and a lot of oil. But, when they really want to get the leaders of the Americas following their lead…. you don’t need nukes or oil or Hugo Chavez. You need Maestro Gustavo Dudamel and his fellow former slum kids in the Orquesta Sinfónica Simón Bolívar.

A mere youth?

Reading the foreign press about Enrique Peña Neito, there’s there’s this continual meme that he is young and dynamic. In a piece for the New York Times, published under his name, the age theme is repeated:

To those concerned about a return to old ways, fear not. At 45, I am part of a generation of PRI politicians committed to democracy.

Maybe 45 is the new 30, as in don’t trust anyone over… but besides not really reassuring anyone that he is somehow committed to a “new” PRI, he is not really young for a Mexican President. The presidents since the Revolution, and the ages at which they assumed officer were:

| Francisco Madero. | 37 |

| Pedro Lascuráin | 57 |

| Victoriano Huerta | 63 |

| Francisco Carvajal | 43 |

| Venustiano Carranza | 55 |

| Adolfo de la Huerta | 39 |

| Álvaro Obregón | 40 |

| Plutarco Élias Calles | 47 |

| Emilio Portes Gil | 50 |

| Pascal Ortiz Rubio | 53 |

| Abelardo Rodriquez | 43 |

| Lazaro Cardenas | 39 |

| Manuel Ávila Camacho | 43 |

| Miguel Alemán | 46 |

| Adolfo Ruíz Cortines | 62 |

| Adolfo López Mateos | 48 |

| Gustavo Díaz Ordaz | 47 |

| Luis Echeverría | 48 |

| José López Portillo | 56 |

| Miguel de la Madrid | 48 |

| Carlos Salinas de Gortari | 40 |

| Ernesto Zedillo | 41 |

| Vicente Fox | 58 |

| Felipe Calderón | 44 |

The average is a little under 48 years of age. Take out Pedro Lascaráin (who was only President for 45 minutes until Huerta assumed office), Victoriano Huerta, and Francisco Carvajal (who lasted four weeks after Huerta fled the country) — none of them elected presidents — and the average is 46 years old… (I suppose you could also take out the 50 year old Emilio Portes Gil — who was chosen by the Chamber of Deputies to replace the 48 year old president-elect Alvaro Obregón after his assassination, but it really wouldn’t change the average).

Peña Neito’s 46th birthday is later this month (the 20th, if you want to send a card… or better yet, ask him for an Soriana Card), so fear not… at the worst, in at least in one thing, he be an average President.

So who won?

So who really won the Mexican election? Notoriously crooked former president Carlos Salinas de Gortari, who will act as the power behind the throne of Peña Nieto, deserves a nod. These next six years will look a lot like the Salinas and Ernesto Zedillo administrations of the 1990s with a scoop of the militarization of the Calderon era for good measure.

The world’s oil giants win. Peña Nieto will back the privatization of Petroleos Mexicanos (PEMEX). Mexico’s oil industry, which accounts for some 40% of the federal budget, has been in state hands since 1938. The privatization of PEMEX has always been a sensitive issue owing to Mexican nationalism, but Peña – like Calderon before him – will fight on behalf of the world’s super-majors against the public interest.

US defense contractors reaping the blood money of Mexico’s “Drug War” also win. AMLO had vowed to halt the flow of gringo “security aid” that sent the Calderon administration on a killing spree. Peña Nieto has said he will continue “the struggle” against a drug-trafficking mafia that is nevertheless knee-deep in the country’s politics. We already know he will hire former Colombian National Police commander General Oscar Naranjo as chief security adviser; an extremely sketchy figure known for both his narco links and long working relationship with Washington.

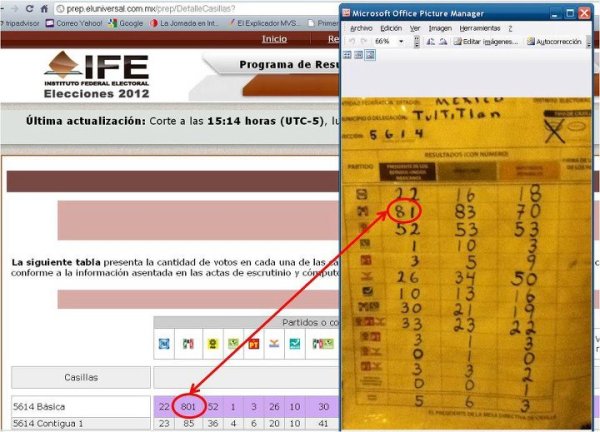

OOPSY!

Human error, I’m sure. I don’t see this arises to the level of a national scandal, but with the scrutiny this election was under, I expect we’ll be seeing a lot more of things like this, and in aggregate we’ll be hearing and seeing a lot of dissenting voices in the next week. And it won’t just be Lopez Obradór people. I heard from a Norteño businessman, in a blue-collar trade, that the anger over the suspected frauds are being heard from just ordinary Josés in places you wouldn’t expect… Monterrey, San Luis Potosí, Juárez…

The Grand Inquisitor

(Thanks to John Donaghy for finding two factual errors, now corrected. My fault, my fault, my most grievous fault!)

The new “Prefect for the Congregation of Faith” appointed today by the Vatican, Bishop (now Archbishop) Gerhard Ludwig Müller may signal a subtle change in Vatican policy towards the Latin American church, and a greater willingness to accommodate itself to the realities of Latin American religious beliefs.

Archbishop Müller’s brief is to head what was, way back called The Inquisition, although the “Congregation of Faith” is also briefed with overseeing cleaning up the various sex scandals that have rocked the Church in recent years and maintaining relations with other Christian sects.

Archbishop Müller’s brief is to head what was, way back called The Inquisition, although the “Congregation of Faith” is also briefed with overseeing cleaning up the various sex scandals that have rocked the Church in recent years and maintaining relations with other Christian sects.

The previous Prefect, U.S. Cardinal William Levada, who reached the mandatory retirement age of 75, was best known in the U.S. for cracking down on nuns, and making nice to the far right-wing, holocaust denying “traditionalist” Saint Pius X Society — a break-away Catholic sect, that was considered heretical, but is somewhat back in the good graces of the Church.

What makes this noteworthy here is that the present Pope, Benedict XVI, had this job under John-Paul II, and was the “holy hit-man” when the Papacy turned against Liberation Theology. Müller, who is also the Pope’s editor, and knew the Pope from the days when both lived in Regensburg (Germany), has ties to Liberation Theologians, and has worked in Bolivia and Peru with Liberationists. He maintains close ties to a former teacher of his, Peruvian theologian and bishop Gustavo Gutiérrez whose 1971 A Theology of Liberation (“Poverty is not fate, it is a condition; it is not a misfortune, it is an injustice. It is the result of social structures and mental and cultural categories, it is linked to the way in which society has been built, in its various manifestations“) gave name to the movement in the Church — especially in Latin America — to develop a “preference for the poor”.

With most modern economic and social theories that deal with class and poverty rooted in Marxist rhetoric, it is somewhat understandable that the old Polish pope — having spent most of his career countering Marxists in his own country — saw liberation theology as a danger to the church, and unleashed then-Cardinal Ratzenburger (now Pope Benedict) to quash the movement. Nor is it is any wonder that so many of the political figures considered Marxists — Jean Bertrand Aristide (Haiti), Hugo Chavez (Venezuela), Fernando Lugo (Paraguay), Rafael Correa (Ecuador), Miguel d’Escoto (Nicaragua), Andres Manuel Lopez Obradór (Mexico) are products of that Catholic movement. Miguel d’Escoto is a priest, Aristide and Lugo were priests; Correa was a lay brother; Hugo Chavez’ parents were both Catechists; and Lopez Obradór worked with Protestant church groups that adopted many of the tenents of Liberation Theology when he was a young social worker. Within the Church itself, you had any number of Liberationist priests and bishops who played an important part in progressive Latin American politics, like the late Mexican bishop Samuel Ruiz and his still living disciple, Raul Vera.

While not always in step with the theology of liberation, the focus on human rights over economic ones inspired prominent churchmen like the gutsy Cardinal Raúl Silva Henríquez of Chile (whose “Vicarate for Human Rights” documented and assisted victims of Pinochet’s neo-liberal fascism and who personally protected dissidents from the Army, going face to face with armed soliders) and Salvadorian Oscar Romero — a theological conservative — who stood up to his country’s U.S. backed dictators and earned a martyrdom for his trouble.

The crackdown under John-Paul II pushed the liberationists to the side, in many cases, replacing liberationist bishops, or liberation-friendly cardinals to the side, replacing them with extreme conservatives, and Opus Dei influenced (or trained) clerics.

In the process, politically active Catholics left the church, often for Evangelical sects. What was once unthinkable in Latin American politics has been for leaders like Hugo Chavez and Andres Manuel Lopez Obradór — both nominally Catholics — to make no secret of their admiration and sometimes open acceptance of Evangelical Christian practices.

Both Müller’s ties to Liberation Theology and his own theological writings defending Protestantism (he wrote his doctoral dissertation on Dietrich Bonhoeffer) make him a much different sort of “Grand Inquisitor” than the previous two incumbents. Whereas the present Pope went after the Liberationists and the retiring Cardinal Leveda tried to mainstream the most reactionary elements or rope in the more conservative factions within the Anglican communion, Müller’s track record is more that of someone less concerned with the issues of the rich nations’ Catholics and more with those of the so-called “developing” nations. That he is already being attacked by the Pius X Society and questioned by Opus Dei means he’s on the right track.

(more: Raw Story, Rome Reports)

Oh-ohhh!

UPDATE as of 9:15 PM (Mazatlan Time) 3-July

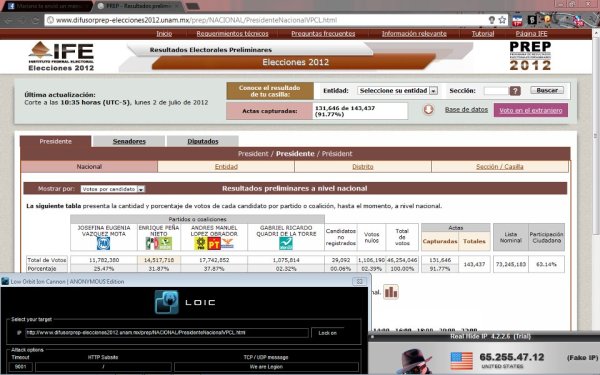

Someone connected (or claiming to be connected) with “Anonymous” hacked into the PREP database, and found data that makes it certainly look like the numbers reported publicly were not the same numbers as the official vote count. What’s a few million votes either way, huh?

http://armakdeodelot.blogspot.mx/2012/07/se-confirma-fraude-anonymous-se.html

I know there’s a pithy quote attributed to somebody about this kind of thing somewhere… Oh… I remember: “It’s not the people who vote, but the people who count the votes ” attributed to Josef Stalin.

On the other hand, it could very well be a fake. While my copy came from an unknown website, Charles II at Mercury Rising, found the same post on a site dedicated to “exposing” Masonic conspiracies and such, which doesn’t lend credibility to the source. Charles raises sensible doubts about the data, but the fact that material like this is floating around, and being considered possible, is not a sign of an electorate that has faith in the process:

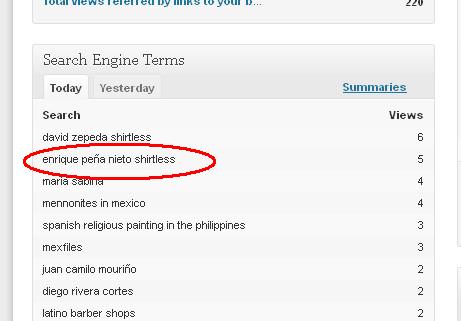

The half-naked and the unread…

We get some very odd hits now an again… I can understand people looking for photos of half-naked telenovela hunks (I’ve written on telenovelas and pop stars on occasion) and why there’d be a couple of people looking up politicians, but five people searching for photos of a half-naked quasi-illiterate politico… ugg!:

Misreading Mexico … by design

Economist Dean Baker takes on the Washington Post (which is probably no worse and no better than any other mainstream U.S. media outlet when it comes to misreporting on Mexico) and in the process writes a succinct essay on the woes we’ll be dealing with (or not) over the next several years:

The Washington Post is heavily invested in NAFTA. At the time of the debate it abandoned any pretext of being an objective newspaper, allowing both its opinion and news pages to be overwhelmingly dominated by proponents of the agreement. Since its passage the Post has refused to acknowledge that the agreement has had the intended effect in the United States of lowering the wages of manufacturing workers. (This is textbook economics. By putting U.S. manufacturing workers into more direct competition with their low-paid counterparts in Mexico, the result is that wages of manufacturing workers in the United States fall.)

The Post also refuses to acknowledge that the deal has failed to improve Mexico’s growth. In fact, a lead Post editorial in December 2007 told readers that Mexico’s GDP had quadrupled since 1988, which it attributed to the benefits of NAFTA. The actual increase over this 19 year period was 83 percent, which put Mexico near the bottom in growth for Latin American countries.

Short, to the point, and should be read in its entirety. Here.

So it begins… or, it ain’t over til it’s over

Based on the “conteo rápido” — which was contracted out by IFE to Mitofsky, FeCal announced that Enrique Peña Nieto is the president-elect… which at this point he is.

While one my late night dog walk, we stopped by the local PRI headquarters (a block and a half from my house), where there’s a rather sedate party going o. Whether the rather staid nature of the affair was due to having to honor the dry law even in Mazatlán on election day itself, or because the PRIistas themselves are not quite sure they have captured Los Pinos (or really care all that much) is something I wasn’t able to ascertain.

I was looking at the IFE PREP figures, both the charts (where AMLO was closing a gap down to under 3.35 percent, when it started to widen slowly) and not at the actual numbers, other than the percentage of precincts counted. However, based on what happened in 2006 (when the results were much, much closer), I expected there would be mathematicians weighing in on what they saw as wrong with the official figures by later this week. I was off by several days.

Jorge López Gallardo, a University of Texas Physics Professor notes that over a period of three hours, the total Quadri + “voto nulo” (invalid ballots) + “NoReg” (write in votes) equaled 4.7 percent.

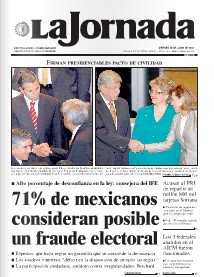

I’m not a statistician (my math skills are slightly below my spelling ability) but on the face of it, that shouldn’t be possible. It might be possible, but in addition to the serious questions about vote buying, media manipulation, election violence (quite a bit, actually, including at least one murder in Guanajuato State), there was a headline in Jornada claiming 71 percent of  Mexican think electoral fraud was a very real possibility. Of course, given the low opinion (especially on the left) of opinion polls, whether it actually is 71 percent is another question… but we can say that a lot of Mexicans assume there was fraud, or probably was fraud involved in the election.

Mexican think electoral fraud was a very real possibility. Of course, given the low opinion (especially on the left) of opinion polls, whether it actually is 71 percent is another question… but we can say that a lot of Mexicans assume there was fraud, or probably was fraud involved in the election.

After the last Presidential election (in which allegations of fraud also were raised, though on a much less well-documented level), enough people took to the streets to seriously annoy the tiny portion of Mexicans that actually need to use certain major streets in Mexico City. HOWEVER, that tiny portion of workers happens to include a lot of the opinion makers … and most of the employees of the various foreign news agencies. The street occupations were presented by the media as some serious threat to the nation, and to the democratic process.

It was a challenge to the process — as it existed then — but I’d argue street actions are democracy in action. Non-violent and rather celebratory (complete with basketball games in the middle of Avenuda de la Reforma), it channeled dissatisfaction with the election into what were useful avenues… the “alternative Presidency” functioned quite well as a resource for developing political and social agendas and unifying the opposition to the incoming administration’s more radical economic and social agendas. On the downside, the incoming administration — with its legitimacy in doubt — doubled down on attacking peripheral social movements (like the one in Oaxaca), more or less forcing the Fox Administration to respond to protests there with military and paramilitary forces (something noted at the time, but ignored by most north of the border commentators). “Plan Merida” may have not followed for some time, but the seeds were certainly there from the election… or selection of the preferred candidate of the Bush Administtation.

I’ve argued before that Peña Nieto is the preferred candidate of the Obama Administration. While the policies that affect the U.S. (pursuing the so-called “drug war” while evading any serious work by the U.S. in clamping down on gun-running and money laundering in their own country, and the continued penetration of U.S. corporate agriculture into Mexico) are likely to be continued (with some cosmetic changes) by the incoming Peña Neito administration, the Calderón Administration will, like the Fox Administration, be pressured into taking measures more in line with the incoming president’s style. Given the authoritarian streak in the PRI, and Peña Neito’s own record in using force to crush dissent, it could get very ugly.

A seminal article by Roger Bartra in Saturday’s El País argues that the return of the “authoritarian right” to power (as opposed to the what he considers the “democratic right” of PAN) is not so bad, that conditions and limits on authoritarian power having been established. Certainly, Calderón and his backers in Washington weren’t able to give into their lower, worse angels although they did have parts of Mexico marching through Hell for the last couple of years.

Creating the limits was part of what all that street noise and “alternative presidential” theatrics was all about. At times it seemed an “authoritarian left” was coming out of the woodwork, but if the authoritarians on the right are part of a legitimate political process, then so are those on the left. Possibly a dangerous situation, as some claimed, but it worked in 2006.

HOWEVER… this is not 2006. For one thing, communications are better, and the “alternative” political actions don’t necessarily have to be out in the public eye, or on the street. The internet wasn’t nearly as widely available in 2006, nor was there anything like “youtube” or “facebook” or “twitter” in widespread circulation. Nor, in 2006, was there an organized, well-educated young dissident movement. There were a good number, perhaps a third to a half, of the “yosoy#132” people on the streets who were not Lopez Obradór supporters.

In 2006, Lopez Obradór was the focus of the protests, and Lopez Obradór was an obsession for those that sought to crush the protests. I’m not sure he matters all that much after tonight. He was seen as the best alternative among the four candidates by a third of the voters, which is about what he received in 2006. A more than impressive performance, and perhaps he really did win the election. At any rate, more than 60 percent of the voters rejected Peña Nieto (and perhaps more voted for him — or didn’t vote for him, but had votes cast in their name — under some sort of duress). As the picture becomes clearer of how the votes were cast, of the younger, better educated and more politically aware voters who backed Lopez Obradór, and — if not on the economic and social “left” at least open to political change.

In 2006, firing a warning shot in Oaxaca was a no-brainer. Crushing poor Oaxaca school-teachers and indigenous protests is easy… crushing middle-class college students and the business executives like Carlos Slim and the intellectuals who despise Peña Neito… and the PANistas who may very well reject the return of the old party… is going to be much, much harder.

We’ll just have to see what happens

They’re all crooks, but as a citizen it’s my duty to vote. Vote and hope.

— 86 year old Mexico City tailor, Mario Rojas, quoted in The Guardian.

None of the candidates are perfect, and I can’t tell people who they should vote for (though anyone who has read this site at all over the last ten years can pretty much figure out which one I’d vote for, if I could), but I urge those of you who are Mexican voters to go to the polls, vote, and hope.

Democracy Interrupted?

One of the main reasons I started this site was finding myself frustrated by the crappy reportage about Mexico that I read in the English-language press. I had some great fun picking out the “editorial filler” in news stories. the phrase “the teeming slums of…” found its way into nearly any Associated Press article filed from Mexico City, whether the incident reported on occurred in Tepito or Polanco or Milpa Alta… or even in some far flung rural area within the Mexico City Standard Metropolitan Area.

With the 2006 election, the key word was “fiery leftist” whenever a reference appeared to Ándres Manuel Lopez Obradór. Today, it’s a some mention of the “drug war”.

More than one foreign reporter I know has admitted that over the past five years, they are obligated to write on organized crime, and that their editors will only consider reportage somehow related to narcotics trafficking. With fewer and fewer media outlets even investing in foreign news, the correspondents and free-lancers have little choice.

Or, when media companies DO send reporters, especially the U.S. media, have been sending war correspondents. And when you’re a hammer, everything looks like a nail. The total absurdity of this kind of reportage was demonstrated recently by the New York Times, when it ran a long, blathering article by Randal C. Archibold and Damien Cave uncovering the fact that people in Juarez try to live normal lives. It took two reporters to figure out that Mexico is not Iraq?

So, by all means I have nothing but appreciation for Jo Tuckman’s reportage for The Guardian, and for The Guardian for having sent Jo Tuckman. It’s unusual enough that a newspaper still has correspondents at all, and Tuckman has done a excellent job, going beyond the “drug war” to talk about current affairs in a complex (and very large) country. Exposing the incestuous relationship between the PRI and Televisa is going to have long-range political and economic impact no matter which party and which candidate wins tomorrow’s election. The effects may be (and I don’t think I’m exaggerating) comparable to James Creelman’s March 1908 Pearson Magazine interview of Porfirio Diáz.

That said, the book she has just published (and one presumes that when a correspondent publishes their book on Mexico, it means they’re leaving the country), “Mexico: Democracy Interrupted”, as reviewed in her own paper, shows the limitations of depending on news reporters for our understanding of a people and a culture.

Alan Knight, professor of the history of Latin America at St Antony’s College, Oxford, the author of several books on Mexican History, reviewed Mexico: Democracy Interrupted in yesterday’s The Guardian:

… As reportage of breaking events it’s fine – reliable and informative. But as analysis, it is often thin and sometimes wrong. There are several problems: the first is the lack of historical depth. […]Tuckman has been an acute observer of Mexico over the last dozen years; but what went on before remains rather murky. For example, the Chinese did not bring narcotics to Mexico in the late 19th century, since Mexicans had smoked tobacco, chewed peyote and puffed marijuana for centuries (hence the lyrics of “La Cucuracha”). The Zapatista rebels of 1994 were not “the biggest group of rebel fighters since the revolution”, as their numbers, fire-power and impact were dwarfed by those of the Cristero – Catholic – insurgents of the 20s.

Perhaps these historical errors don’t matter much. After all, this is reportage. But two more problems arise. The central theme of the book is Mexican democracy, and while Tuckman gives us abundant facts and illustrations, she offers no clear analytical framework, no general interpretation of current trends.

[…]

A more pertinent question is whether Mexican democratisation is for real and thus difficult to reverse, even if the PRI returns to office. […] Tuckman seems to have stuck to journalists and public intellectuals. She muddles up representative and “participatory” democracy; and she entertains inordinately high standards of what – liberal, representative – democracy should entail, standards few countries attain.

Being a non-academic historian, who has done some reporting, I probably have to cut Tuckman some slack for — in the typical way of we English-speakers — for her hyperbole in considering the “drug war” as more important than the Cristero War (though I could have recommended an excellent non-academic book on Mexican History, written especially for those English-speakers who are planning to do any sort of business in this history-obsessed country… and something on the Cristero War as well!). Journalists do deal with the here and now, and contexualizing the present in terms of the past in anything but the most superficial of ways is just not possible within the space of a newspaper or magazine article.

Professor Knight’s second criticism, that Tuckman “muddles up representative and “participatory” democracy; and she entertains inordinately high standards of what – liberal, representative – democracy should entail” illustrates a more chronic problem with foreign writing about Mexican political culture.

I won’t go so far as to say the attitude is “imperialist” (especially about anyone working for a lefty touchstone like The Guardian), but it is looking at Mexico though what Nezua, the Unapologetic Mexican, once called “the white lens”: the sense that things not done the way “we” do them is inferior, or wrong.

Not that we “embedded foreigners” don’t often let our biases color our own perceptions and misread cultural and political events through our own “lens” (the late John Ross saw the Mexican Revolution as a “failure” for not following the rules laid out in the Book of Marx), but we are able to ask ourselves questions that may straighten out the distortion. Why is a two-party state automatically preferable to a multi-party, or quasi-single party state when it comes to personal freedom? Is the British surveillance state a democracy, or a police-state. Are our inefficient police a sign of weakness, or a sign that the people look out for themselves? Aren’t social movements and demonstrations a form of democracy, and why don’t people in the United States take to the streets when a candidate loses by a close margin? Do they fear the democratic process, or are they resigned to fraud?

I will be curious to see what Jo Tuckman says about our “interrupted democracy”, and — understanding she is not a historian, and is likely to make mistakes — what insights she gleaned from those “journalists and public intellectuals ” who — important as they are to our lives NOW — are only singular figures in a political and cultural history measured in millenniums, and not in presidential administrations,and not in the tenure of even the most gifted of correspondents.

Nobody?

In late June six years ago, nearly everyone predicted it [the 2006 Mexican presidential election] was going to be a very close election, which is exactly what happened. Nobody predicted that the new president would launch a military offensive or that the conflict with criminal organizations would turn as violent as it has. Nobody saw the H1N1 pandemic, Mexico’s ups and downs as the global economy hit a crisis, or the fact that Calderon would turn out to be a pretty good leader on environmental issues. Few believed the PRI would bounce back from their election loss to regain their status as the country’s top party.

I like Boz, and I read him regularly, because he has a good handle on the “inside the beltway” thinking of the Washington establishment, especially the military establishment. By “nobody”, I presume he means “nobody” in his circle.

While I don’t think anyone could have predicted the over-reaction to the H2N1 flu scare, and the real surprise of the world economic crisis wasn’t that Mexico experienced some ups and downs, but that it avoided the disasters predicted by the establishment thinkers. That Banamex managing to keep Citibank afloat was probably the most unexpected turn of events, though the unspoken role that our narcotics exporters played in keeping the existing banking system from total collapse is unlikely to win any accolades.

As I was saying six years ago (and as a lot of us so-called “lefties” were saying), Felipe Calderón was looking to to set up a militarized conflict … and did, even before Vicente Fox had left office (remember Oaxaca?). As we all pointed out, PRI was still the country’s major party and the Mexican establishment — left, right and center — were taking climate change quite seriously.

But, what’s said in Mexico is said by… nobody.