Double whammy!

* According to pollster María de las Heras, Peña Nieto pulls 39 against 31 of AMLO

* According to pollster Covarrubias y Asociados, Peña Nieto pulls 36 to AMLO’s 27.

This is truly stunning. With one month left of the race, the outcome is increasingly open.

Covarrubias polls for a pro-AMLO on-line publication, SPDNoticias, but is also the pollster for the conservative Madrid daily, El País, which suggests a balanced approach. María de las Heras USED to be Milenio‘s pollster, but either quit or was fired (depending on who you believe) over (again who do you believe?) pressure to manipulate polling results or using unorthodox sampling methods.

What I find TRULY STUNNING is not that these polls show AMLO much closer to EPN than the polls quoted by the foreign press and the major dailies here,but that these polls are being reported by the two major financial papers… more evidence that the establishment is not nearly as frightened of the candidate of the left as his rivals’ political machinery would like to think.

And, I told ya’ so..you can’t predict the outcome of Mexican elections months in advance, and I said AMLO was likely to do much better than was being predicted. He might even win.

Patrick Corcoran has also been reading Diego Valle -Jones’ recent series of statistical analysis of Mexican divorces.

Chihuahua is the state with the highest divorce rate, which means that the relatively high likelihood of a marriage ending through violent death did not overwhelm the other factors (i.e. the lack of prevalence of Catholicism) in keeping the divorce rate up.

Marriage and divorce are covered by state law (or Federal District law) in Mexico, but the marital status granted in any entity is recognized throughout the Republic. Best known is the Federal District’s same-gender marriage law, which means persons of the same gender who are get married in Mexico City are recognized legally as a couple everywhere in Mexico. The Federal District also has the only “no-fault” divorce laws in the country, which seems to factor into the odd statistical fact that there are more divorces in the Federal District, but less divorces by people who were originally married in that entity.

It’s obvious that couples seeking divorces without complications (child support and spousal maintenance are separate from what the Federal District calls “divorce expres”) are getting un-hitched in the Capital, but that doesn’t explain why people originally married there have less divorces. Surely, it can’t be they’re going to Queretaro when they need … uh… um… spousal relief.

Diego doesn’t show any data on same-gender divorces, but if it existed, he’d dig it out. And he’s to be commended for providing more cheerful reading than the usually appalling tally of the butcher’s bill in the war on (some) drugs.

God, Gays, Ganja and Mexican Politics

Seriously good article on some overlooked campaign issues.

Kent Paterson, Frontera NorteSur

Center for Latin American and Border Studies

New Mexico State University

Las Cruces, New Mexico

In the United States, evangelical leaders have been at the forefront of pushing prayer in public schools. But in Mexico, they are in the vanguard in opposing it. While the so-called narco war and economic distress are generally regarded as the top two issues in this year’s electoral races, fundamental issues of church, the state and religion are also swirling around the political scene. A flash point is the Mexican Congress’ recent approval of changes to Article 24 of the Mexican Constitution.

Seemingly innocuous, the reform guarantees the right to practice religion in “public as well as private” places. Supported by President Felipe Calderon, the reform was passed last December by Mexico’s Chamber of Deputies just as the country was shutting down for the long winter holiday break. In March, as Mexico was gearing up for another extended holiday season, the Senate followed suit.

According to La Jornada daily, National Action Party (PAN) Senator Sergio Perez Mota justified the reform as a necessary one to prevent Mexico from sinking into a “lay state” that curtails “essential freedoms.”

Although the reform also contains language that defends the secular character of the Mexican State, opponents contend it could open the door to religious instruction in public schools.

On a recent day in Ciudad Juarez, members of the Lay Mexico Civic Forum gathered on the downtown plaza to pass out leaflets and collect signatures on letters calling on the Chihuahua State Legislature to reject the constitutional reform.

“If a person wants to teach his or her child a Christian education, then let him or her go to a Christian church,” said Lay Mexico Civic Forum member Sal Coronado. Introducing religion into the public schools, Coronado insisted, could lead to discrimination, religious bullying and academic complications.

“What are they going to teach?” Coronado asked. “The Catholic, the Mormon or the Christian (Protestant) religion?” Holding aloof banners, Coronado and fellow activists greeted a steady stream of people stopping by their table to ask questions and sign the letters to Chihuahua lawmakers.

Backed by Protestant churches, the Lay Mexico Civic Forum has shown an impressive capacity to mobilize supporters, turning out thousands of people in street demonstrations across the country in recent months. For the congressional reform to become part of the Mexican Constitution, a majority of Mexican states still have to approve it. In May, the state legislatures of Baja California and Michoacan joined the state of Morelos in shooting down the reform.

Critics charged that the Congressional action was undertaken without adequate public discussion, and unneeded in a country that already guarantees religious freedom. Victor Silva, president of the Michoacan State Legislature and a representative of the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), said public forums and consultations should have preceded the federal legislative action.

“For this reason we are not going along with it,” Silva was quoted in La Jornada.

Earlier writing on Catholic.net, Guillermo Gazanni Espinoza contended that Article 24 reform opponents from center-left political parties were mistaken in declaring that the change was done to benefit the Catholic hierarchy or lay the groundwork for the Pope’s Mexico visit last March.

According to the Council of Catholic Analysts of Mexico, the reform, as proposed in the Chamber of Deputies by the PRI’s Jose Ricardo Rodriguez Pescador late last year, was merely meant to bring the language of the Mexican Constitution in line with Article 12 of the American Convention of Human Rights, a section of the hemispheric agreement upholding religious liberty.

Particular details of language and political intent aside, the Article 24 controversy cuts much deeper than the polemic over constitutional reform. The issue spotlights shifting political tendencies, deep changes in Mexican society and culture, rekindled church-state flirtations and the hard imperatives of the 2012 elections.

At stake is the lay character of the Mexican state, which arose from historic 19th century showdowns between liberals and conservatives that curbed the power of the Roman Catholic Church, regarded by liberal forces as an institution tied in with the system of domination and exploitation dating to the Spanish colonial period.

Mexican clergy have long been banned from political involvement, but rapprochements between successive presidential administrations from both the PRI and PAN parties and the Vatican have revived controversies over the Catholic Church’s role in politics in recent years.

The Pope’s March visit to Guanajuato, an event attended by all the presidential candidates, only further solidified this trend in the view of many analysts.

Likewise fanning church-state controversies are conflicts over gay marriage, sex and abortion. The legalization of early term abortions and gay marriages in Mexico City during the past few years under center-left PRD administrations produced a political backlash in other Mexican states- still referred to as “La Provincia” by some capital city residents. In historically conservative states like Aguascalientes, women have even faced criminal prosecutions for having abortions.

In this broader context, the Article 24 fight erupted on the political landscape. “The parties want votes, and there are issues they won’t touch because they might lose votes, including issues of abortion, school prayer and drug legalization,” said Armide Valverde, principal of Ciudad Juarez’s Alta Vista High School. A career public educator, Valverde endorsed secularism as one of the pillars of the Mexican education system. “There’s no reason for (religion) to be part of education,” Valverde said. “That’s why the Church exists.”

Whether the candidates like it or not, hot-button social issues are popping up on the campaign trail this year. Speaking at Mexico City’s private La Salle University last week, conservative PAN presidential candidate Josefina Vazquez Mota fielded touchy questions from students about gay marriage, abortion and drug legalization. The questioners hailed from an age demographic that could be the decisive vote in the 2012 elections.

Mexico’s only female presidential candidate in a contest with three men, Vazquez Mota appeared to have attempted to stake out a middle ground response by not directly answering the specific question about gay marriage, saying instead that she was “absolutely respectful” of individual sexual orientations, according to report of the encounter in Proceso’s Apro news service.

On the abortion question, the former Calderon administration official defined her position as “pro-life,” but quickly added that she was against criminalizing women who got abortions. As for marijuana and other illegal drugs, Vazquez Mota affirmed that she was open to a debate but worried about going down the road to legalization before strengthening government, law enforcement and justice institutions.

Finally, Protestant/Catholic divergences are evident on matters like Article 24. While Mexico is still a majority Catholic country, more and more Mexicans, like other Latin Americans, are joining different Protestant sects. The Seventh Day Adventists, Jehovah’s Witnesses, Methodists and followers of the Jalisco mega-church Luz del Mundo, among others, have a firm and growing base across the country. For many Protestants, the Article 24 reform threatens a return to Catholic domination and discrimination against their own faith.

At the Lay Mexico Civic Forum event in Ciudad Juarez, a shoeshine man sat in front of the activists’ table. Taking time to chat with a reporter, the man declined to give his name, not because he was “afraid,” he insisted, but because divulging his identity would be a vain act that takes away attention from God. Summing up the posture of many Article 24 opponents, the man pulled out an old phrase from his linguistic hat: “Render unto Caesar the things which are Caesar’s, and unto God the things that are God’s.”

Pavane for the Red Princess

Elena Poniatowka celebrated (and Mexico celebrated) her 80th birthday on Saturday. But more importantly, next year will mark the 60th anniversary of the transformation of Princess Hélène Elizabeth Louise Amélie Paula Dolores Poniatowska Amor from “su altessa” into something much more impressive… “nuestra Elena”, queen of Mexican journalists.

Elena Poniatowka celebrated (and Mexico celebrated) her 80th birthday on Saturday. But more importantly, next year will mark the 60th anniversary of the transformation of Princess Hélène Elizabeth Louise Amélie Paula Dolores Poniatowska Amor from “su altessa” into something much more impressive… “nuestra Elena”, queen of Mexican journalists.

Reading Michael Schuessler’s informative, intimate, opinionated (in the best possible way) and witty Elena Poniatowska: An Intimate Biography (Tuscon: University of Arizona Press, 2007), I was amused and more than a little relieved to learn that Poniatowka herself attributes her long and successful writing career mostly to not being trained to do anything particularly useful.

Although being royalty is, I suppose, a job in itself, it’s not likely the Polish monarchy will be restored (she is the heir to throne that has been vacant since 1798), nor the French one (Louis XV’s consort, Marie Leszczyńska was another relation), nor the first Mexican Empire (through her mother, she is ALSO descended from Augustin Iturbide, Emperor Augustín the First… and last). Still, there’s a place in this world for pretty, intelligent and well-brought up titled women, especially in Europe where such things still matter to people.

Born in France, where her family has been established since Józef Antoni Poniatowski was appointed a Marshall of France by Napoleón Bonaparte, she should have been whisked around to the various family estates for her early training, but the German invasion forced her mother to take refuge with her grandfather in the south of France, where she attended the local school. The outcome of the war being in doubt in 1942, Princess Hélène’s father, Prince Jean, dispatched his wife and daughters to the relative safety of Mexico.

There were a handful of other royals rattling around Mexico due to the war, and a bit of exoticism in the upbringing wouldn’t hurt when it came time to enter the royal marriage market. Despite the odds, she did learn a useful skill while sitting out the war. Her mother, not expecting the stay in Mexico to be more than an unfortunate sojourn, sent her children to a British school rather than one for upper-class Mexicans. As a result, Princess Hélène to this day speaks the earthy, common Mexican Spanish she learned from her nanny.

While the war was over, France was in ruins, and it seemed wise for the family to remain in Mexico, where the family’s financial situation was more settled, and where there was an upper class that gave deference to European titles. Despite its reputation for a shocking level of tolerance and crass materialism, the United States was considered the proper place to educate the children of the Latin American elite… within certain strictures. Princess Hélène and her sister were packed off to a convent school in Pennsylvania.

While it is easy to make fun of such schools, they are intellectually rigorous as a rule, and the school she was being prepared for a college education. Which — between the fall of the peso in the early 1950s, coupled with political and economic problems in France— had to be put on hold. I don’t think even the most creative of nuns could have figured out a way to justify giving a foreign princess a scholarship and one can’t imagine royalty going into a Pennsylvania bank and asking for a student loan. Still, with the expectation that marriage to a rich, if not titled, husband was the most likely scenario in the not-too-distant future, Princess Hélène was packaged as a debutant and … as a backup in case she needed to actually God Forbid take a job for a time … took some secretarial classes, adding typing and shorthand to her relatively marketable English and French language skills. And as it is, she never married a prince, finding her life’s partner among more stellarn regions … astronomer Guillermo Haro.

As it turned out, the typing and shorthand were useful, but what got her a job was that title… and knowing the right people who knew the right people.

When the Revolutionary Party became the Institutional Revolutionary Party in 1949, it signaled more than just the Revolution was here to stay. It also meant that the new social order — with a mix of those for whom “the Revolution did them justice”… i.e., prospered, as well as the pre-Revolutionary elites who’d held on to their wealth or status (or both) were somewhat legitimized in what had been a radically socialist and leveling society. Being somewhat insecure, and new at being high society, there was a tremendous need for confirmation of their place in the social scene. The Mexican press needed society page writers.

Poniatowska, under a couple of different pseudonyms in the early years, was particularly well suited to the task, and reinvigorated the form, basically, as she cheerfully admits, because she really had no idea of what she was doing. Royals, after all, feel their place in the social order is secure and have no reason to read about themselves, and the peer group to which she belong was pretty tiny. Being naturally curious, it wasn’t so much a question of asking how the “other half” lives, but how the other 99.99 percent of Mexicans live.

While she interviewed (and still occasionally interviews) the luminary or the legitimately celebrated, she discovered her true vocation in interviewing the less known, seemingly unimportant Mexicans who are worthy of celebration and acknowledgement. Her famous friendship with the irascible Josefina Bórquez, who Poniatowska found as fascinating and worth-while an acquaintance as any any society lady or film diva or intellectual, and whose hard-scrabble life-story was fictionalized as that of Jesusa Palancares suggests what side of the growing political divide in Mexico Poniatowka would end up. With Tlatelolco, as a journalist, the Princess felt she had no choice but to be on the side of the students, against the elites to which she belonged, but were bent on destroying their own, and denying they were going about it.

Not that high society doesn’t have its uses. Teaching a “writers workshop” for the ladies-who-lunch when the city in was plunged into chaos by the 17 September 1985 earthquake, some of her students found themselves not just serving sandwiches, or buying shovels. The ineptitude of the official response was obvious, but someone had to record it. The ladies who lunch were sent out with pencils, paper, their eyes and their ears. The city was short of everything, including journalists, and more than a few society ladies found themselves lauched on a meaningful career.

The earthquake drove the writer now famous as “Elena” (the French “Hélène”) further to the arms of the people. Working on a crew moving rubble, she was struck by the the punk rockers in her brigade. They didn’t defer to her because of her title, or her social standing, but simply because she is a tiny older woman willing to work. It reminded her, as she mentions in Shuessler’s book, that essential nobility and chivalry are not the province of those to the manor born, but of the Mexican people in general…. and who were given voice by Poniatowska in her 1988 Nada, nadie. Las voces del temblor (Nothing, Nobody: The Voices of the Earthquake)

An unnatural disaster… the Salinas administration and NAFTA… has pushed her firmly into a political position on the left, which she sees as the side of those noble and chivalrous Mexicans. She is not a Communist, but having written a novel about Communist organizer Tina Modotti, and with her identification with the Mexican political left, her European relations have taken to calling her the “Red Princess”.

While I cannot take a political stance in the upcoming presidential election, let me just say that in the next Administration, I certainly hope that Secretaria de Cultura Poniatowska continues to write, continues to introduce us to the true nobility among us, for many more years to come.

(Photo Credit: El Universal)

Caption time

Yes, that is Onésimo Cepeda Silva. The former boxer turned priest, NASCAR fanatic, PRI militant, scammer and schemer (his family had a pyramid scheme going where they were selling funerary niches in the Cathedral… betting that by the time you tried to collect you’d be dead anyway. Pretty slick), art thief and forger and — in Aguachile’s words — “thug bishop”, has led the Diocese of Ecatepec since its creation 17 years ago. Cepeda recently turned 75 which means he had to tender his resignation to the Vatican. Which accepted it.

Looks like he’s replacing Jake Blues and joining the band. Though the Blues Brothers were relatively honest folk going about their mission from God.

Que vivan los estudiantes!

For Quebec, Chile Mexico…

The late Mercedes Sosa…

Mario Gutiérrez: “I’ll have another”!

He does… another winning ride in the Triple Crown on, of course, I’ll Have Another. The Jarocha jockey and “I’ll Have Another”, having crossed the finish line at the one and 3/16 mi. point on the Pimlico racetrack in 1:55.94 minutes… just ahead of Mike Smith, riding Bodemeister … again. There’s Belmont to come, where we can expect Mario and I´ll Have Another to … have another.

More on Mario Gutiérrez.

But this did surprise me

There were “Occupy” protests throughout the United States today (as well as similar protests in Europe), and Mexico also saw major street protests.

At first glance, the Mexican “anti-Peña Nieto” marches would seem to be unrelated to those elsewhere. The largest, in Mexico City, attracted somewhere (depending on which report you accept) between 25 and 50 thousand (or more) demonstrators. I think the crowd may have been significantly larger. The photo at left shows Reforma, from the Angel — at calle Florencia and the palm tree is about a third of a kilometer’s distance. The street here, with a parks on either side, is equivalent to a 12-lane highway). There were coordinated protests throughout the Republic, but the crowd estimates have to be taken with a large grain of salt, given WHAT was the real object of the protests

At first glance, the Mexican “anti-Peña Nieto” marches would seem to be unrelated to those elsewhere. The largest, in Mexico City, attracted somewhere (depending on which report you accept) between 25 and 50 thousand (or more) demonstrators. I think the crowd may have been significantly larger. The photo at left shows Reforma, from the Angel — at calle Florencia and the palm tree is about a third of a kilometer’s distance. The street here, with a parks on either side, is equivalent to a 12-lane highway). There were coordinated protests throughout the Republic, but the crowd estimates have to be taken with a large grain of salt, given WHAT was the real object of the protests

While rejection of the PRI candidate (not necessarily in favor of AMLO) was the calling card, the impetus for the “Marcha anti-Peña Nieto” has been the PRI’s co-option of the mainstream media and the allegations that polling organizations and the like are misleading the public into believing a PRI presidential victory is a given.

Although there have been larger marches in Mexico City in recent years … notably “anti-crime” marches, they were pushed and propagandized incessantly by the television networks with the support of the Administration. Televisa being one of the chief targets of the protesters, it wasn’t about to receive free PR on their news broadcasts (well, come to think of it, Peña Neito’s constant presence wasn’t exactly “free” … something marchers were eager to bring to the public’s attention). There was very little mention in the regular press, not even in the reliably leftist la Jornada (which doesn’t have a large circulation nationally, anyway).

Although there have been larger marches in Mexico City in recent years … notably “anti-crime” marches, they were pushed and propagandized incessantly by the television networks with the support of the Administration. Televisa being one of the chief targets of the protesters, it wasn’t about to receive free PR on their news broadcasts (well, come to think of it, Peña Neito’s constant presence wasn’t exactly “free” … something marchers were eager to bring to the public’s attention). There was very little mention in the regular press, not even in the reliably leftist la Jornada (which doesn’t have a large circulation nationally, anyway).

The “anti-Peña Nieto” marchers were organized was on the internet… through Facebook and Twitter and by mention in blogs and emails and some of the alternative on-line publications (mostly pro-AMLO). I’d seen mention of it, to be sure, but didn’t expect anything much beyond the usual Mexican mass protest — a march down Reforma, some inconvenienced drivers, a few passionate speeches and… maybe a picture or two in the morning papers. Not only did it come off, it appears that motorists weren’t inconvenienced, but were showing their support for the marchers.

That not all the protesters were students and youngsters (campesino groups and the electrician’s … two groups that you expect to show up at any lefty event were there, along with others), it does appear to be a younger crowd that turned out. I haven’t seen the Televisa coverage (and I don’t watch much TV these days), but media outlets like Milenio-TV, connected with the pro Peña-Nieto Milenio newspapers, focused on the “youthful” crowd. So did Roy Campos, of the Mitofsky polling group. Campos is quoted by Reuters as pointing out that 18-24 year olds are 13 percent of potential voters.

Pollsters are said to be in the bag for Peña Nieto (which may be wishful thinking). I too doubt the pollsters, but because I think the Mexican electorate and electoral landscape has changed rapidly, and the assumptions used in drawing up polls, and the wording of the questions, may be skewing the results. Campos, making the assumption that the anti-Peña Nieto “front” (if that’s the right word) is ONLY the traditional University student age cohort, illustrates what I mean. While that is the group most likely to use the internet (and cell phones and facebook, etc.) to organize protests, and it has been the universitarios that have been the most active in pushing this unusual “anti-campaign”, they may be only the tip of the iceberg. And, here in Mexico, getting a university education is still somewhat of an event in a family, and the student(s) in one’s extended family are likely to be listened to by their relations with much more respect than one might give older family members.

Though not always, apparently. In this clip, from Colima, an “adult” PRI supporter punches out … ironically enough… not a anti-Peña Nieto marcher, but a reporter — you know, one of those media guys —

… well, we use maleducado for “ill-mannered boob” and not just “dumb shit” for a reason.

In the next few days, we’ll see how this is spun by the various media chains, and by the parties. From comments on various websites, I expect the Peña Nieto campaign will be pushing the meme that the protests were too well organized to be an amateur production. “Anonymous” — which based on their supposed attack on the “cartels” and their Anglo-Texan supposed spokesperson trying to sell a book contract, as well as the Castillian accent used by their masked on-screen speaker makes me extremely skeptical of their connections to Mexico, and their purposes — launched a denial of service attack on Peña Nieto’s campaign website, timed to coincide with the marcha.

If Anonymous was involved in the movement, it is unfortunate, but the overall rejection of politics as usual, and the demand for more accountability from the establishment leadership (here, the media and the political parties), is not all that different from what is driving the “Occupiers” and “Inconformes” elsewhere in the west. Or the Arab Spring, or the Chilean student protests, or the…

Why am I not surprised?

I originally drafted this post this last week, but was waiting to see if there were further developments… boy howdy, were there ever!

Mexican army soldiers detained 17 suspected Gulf cartel members and a Cuban man who was allegedly providing them with weapons training in the northeastern state of Nuevo Leon, officials said.

…

In mid-March, army soldiers detained two Honduran ex-military men, 41-year-old Roger Ivan Lopez Davila and 21-year-old Carlos Alfredo Herrera Gomez, who had been in Mexico for two years training gunmen with Los Zetas.

Back in September 2008, I mentioned Cuban gangsters working with one of the organized crime groups in the Yucatán. One got the sense — especially given that the gangsters were involved in smuggling Cubans to the United States — that the Cubans were more connected to groups in the U.S. than on the Island. Both Mexican and Cuban investigators suspected as much. The Cuban investigators spoke of the “Miami Mafia”, although whether they meant organized criminals in the pay of political dissidents, or the political dissidents themselves wasn’t always clear.

I don’t say that to denigrate Cuban exiles. Although I’m not likely to be in favor of their goals (or their methods), it would be foolish to pretend that even the most honest and upright of insurgents are by definition on the wrong side of the establishment that makes the laws, and — in the long run — the criminals sometimes end up on the side of the angels. My favorite example is the “Conspiracy of the Righteous” —in which the very brave, stern Calvinist villagers of Prélenfrey-du-Guâ in the French Alps worked with Parisian forgers and counterfeiters as to shelter Polish Jews during the Nazi Occupation. Conversely, the Cristero movement came to an inglorious end in good part because they depended on incompetent smugglers to supply weapons from the United States — specifically the Knights of Columbus. The K of C just didn’t know the right wrong people. Gorostieta should have contacted Al Capone instead.

That Cuban political dissidents are involved in smuggling people through Mexico is no secret. That apolitical criminals working with political dissidents are likely engaged in other enterprises isn’t anything new either. Trading narcotics for weapons, as a political tactic, goes back at least to Pancho Villa (who was something of an exception to the rule, rejecting the advice from his respectable financial advisers to trade opium for weapons in the United States… and, as we know, Villa eventually was cut off from U.S. weapons, so maybe he should have listened to his advisers).

So… with the Mexican gangsters all in narcotics, weapons and people smuggling business (and having become quite successful at it), why would anyone be surprised to it would be no more surprising to find criminals turning political as it would be to find political people going rogue. I don’t think anyone was shocked when Cubans were thought to be involved in all three in the Yucatán, which only came to light after investigation into the beheadings in the Yucatan in August 2008. Nor, should anyone be shocked when another mass execution and beheading comes to light, also involving Zetas and Gulf Cartel rivalries, and what appears to be a people-smuggling operation … and a Cuban “trainer”.

Roberto Rodríguez Sánchez, the alleged trainer, is described in Mexican news reports as a native of Cuba, but not a Cuban, and it doesn’t appear he’s been living on the Island in a some time. As it is, popping up in China, Nuevo Leon (about half way between McAllen, Texas and Monterrey) makes it seem unlikely that his criminal activities had anything to do with Cuba… or at least Cubans in Cuba… directly.

China, Nuevo Leon, is on the smuggler’s highway to and from the United States, and there is a lively trade in weapons, narcotics and undocumented workers going back and forth through that community.

Espionage? Univision quotes Jorge Domene Zambrano, the government spokesman on public security as saying Rodriquez’ capture dismantled an important espionage web working for organized crime.

… and this is where things got really weird and makes me glad I waited before posting …

With three generals arrested this week (including former deputy secretary of defense, Tomas Angeles Dauahare), and another high ranking officer also detained, allegedly for ties to the Beltran-Leyva gang, which despite supposedly having been wiped out, is actively allied with the Zetas, and at war with the Gulf Cartel.

The forty-nine (so far) anonymous dead … who may have been Central American migrants … appear to have been victims of a particularly nasty exchange — human beings for weapons or cash — which had the apparent support of Mexican military and government officials, and the complicit support of the Cubans. That the only beneficiary of all this is Chapo Guzmán (who despite being labeled public enemy #1, and said by those who write about gangsters, scheduled to be “eliminated” ahead of the election, seems to have been forgotten by all reports about this), the Beltran-Leyva gang being an insurgent group within his own organization that went over to the Zetas, and appears to have enjoyed some support within the government.

None of which surprises me in the least.

Yeah… this one:

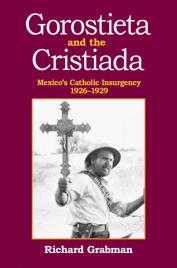

Available as an e-book worldwide (here) and also in a printed version distributed in Mexico.

Catholic News Services’s David Agren provides some balance to the bally-hoo surrounding the Gorostieta movie, released as “Cristiada” in Mexico and “No Greater Glory” in the U.S.

The rebellion saw Catholic clergy and laity taking up arms to oppose government efforts to harshly restrict the influence of the church and defend religious freedom. In the end, the rebellion of the Cristero — soldiers for Christ — was quelled in 1929, leaving the church sidelined for much of the last century and its role limited to a pastoral concerns with no say in the public policy arena.

Ask Mexicans about the rebellion and the answers about what it means today depends on a person’s point of view.

Catholics leaders consider the government’s actions to limit church influence that led to the rebellion an attack on religious freedom. Self-described liberals and many in the Mexican political and intellectual classes consider the suppression of the revolt a triumph of the secular state. Some academics and authors are less passionate, describing the uprising as an agrarian conflict with political and religious overtones.

[…]

“It was a violent era and there were a lot of ambitious generals. Gen. Gorostieta was one of them,” said Richard Grabman, author of “Gorostieta and the Cristiada, Mexico’s Catholic Insurgency 1926-1929.”

“The Cristeros attracted a lot of people that were not necessarily religious, but looking for a military solution to social problems,” he said.

Mexico had emerged from a violent revolution during the 1910s, which was fought mainly to end the enduring rule of then-President Jose de la Cruz Porfirio Diaz and give properties to the landless peasants being exploited by hacienda owners.

[…]

Many of the Cristeros were small landowners, unlike those taking up arms in the revolution.

Haciendas were less common in the main areas of the conflict, which covered an area of west-central Mexican known as the Bajio.

“Cristero were small landowners threatened by social change,” Grabman said. “They feared (agrarian reform) would be collective agriculture.”

The relationship between the Bajio landowners and their workers was different from the exploitation on haciendas suffered by peons taking up arms in the revolution.

“They saw their farm workers as family, instead of peons,” Grabman said.

Gorostieta, the retired general, had experience with attempting to suppress peasant uprisings in Morelos state, fighting the forces of revolutionary leader Emilano Zapata, whose troops were fighting for “land and liberty.” Grabman said it left an impression on Gorostieta when he learned that “farmers without military training could be a formidable force when fighting for a belief.”

Other people are quoted too — as they should be.

Via Los Ángeles Press, which as it’s name suggests, is based in the United States… which in some ways allows it to provide better coverage of Mexican politics than Mexican based news organizations.

What’s a shame is that many in the better known foreign news organizations simply accept the official stories put out by the Mexican government and the Mexican “mainstream” — or (like the U.S. press especially) focus on foreign affairs only in relation to U.S. policy, and ignore “outside the box” reportage that may uncover startling — and potentially highly important — news. Smaller, independent organizations, like Los Ángeles Press, have the ability to go for these stories, but don’t always have the resources, but to their credit find alternative sources usually dismissed by the mainstream. Like this, from Hispan_TV’s Ramses Ancira.

This report focuses in on what appears to be a false impression being given (deliberately?) by Mexican media (specifically Televisa and TV Azteca) which is being echoed in the foreign press: namely that Enrique Peña Nieto actually is the leading candidate for the Presidency, but might be dismissed simply because Hispan-TV is a Tehran-based satellite network (the only Spanish-language network in the Middle East), but considering that the Iranians don’t have much of a stake in the Mexican presidential elections no matter who wins, the report should be taken as seriously (and as skeptically) as any other.

Ridin’ that train…

The fare on the Metro may have gone up to three pesos now, but it is still as amazing an experience (especially compared to taking the bus) to find yourself whisked around the metropolis now as it was when Chava Flores first wrote this little train ridin’ song (performed by Oscar Chavez) back in the early 1970s.

I’ve been in every one of the Metro Stations mentioned in the song, but I don’t think that’s particularly unusual.